1.

Francesca Woodman made her photos out of what she had. Trees, eels, hosiery, lace, mirrors, Vaseline, clothespins, garter belts, silverware, peeling wallpaper.

One of her most profound images only occurred because a truck hauling flour crashed outside her RISD apartment. Somewhere during my research on the artist, I heard a story that claims Woodman saw the overturned truck and immediately called some friends who helped her to carry as much of the loose flour into her studio as possible. She spread it across her wooden floor and, using her own body, made a shape somewhere between a snow angel and a corpse’s chalk outline in the powder. She then posed beside her own outline, nude but for a pair of Mary Jane shoes.

This photo is a litmus test.

For some, a girl haunting herself.

For me, a genius who is a woman.

Perhaps those two impressions are the same: both saturated with ex nihilo, with birth, with using the stuff you manage to unclasp from the world to create something that is your own.

Francesca Woodman. Untitled. Providence, Rhode Island. 1976.

2.

Fifty years after this photo is taken, I wake up in the middle of the night. I am in Kansas, early June, and so the most comfortable hour of the day is before sunrise. When my mother worked the night shift, she had to walk from the hospital where she was a nurse to her car in the predawn hours. One of the spikes in my memory, a sort of anti-trace, is of her telling me that 4:00 am is actually the most dangerous hour of the day because that’s when testosterone surges. Most rapes occur at this time, she explained.

I tucked a hot pink bottle of mace into my running jacket that morning. Six months earlier, Trump had been elected president. The Friday after that, I passed my doctoral exam. There was an ambient terror—a sense of being tested—that would not really crystallize for me until the testimony of Christine Blasey Ford.

The town was empty that morning. I ran with the thrum you get when you aren’t where you are supposed to be, when you are aware of threat.

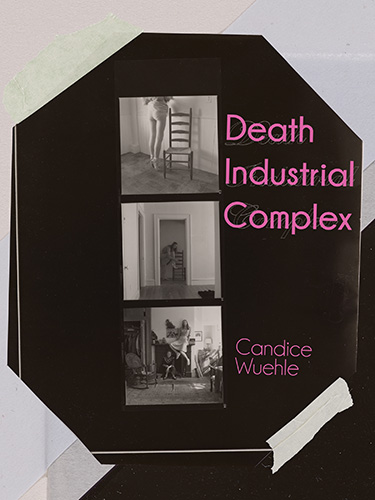

This is the condition I am in when I returned home, the house still dark, and sit down to write what will be Death Industrial Complex.

I cannot say I felt possessed as I began the first poem in a book concerned with a dead woman, a suicide, although I have described this feeling to friends as a possession.

What I actually felt was the opposite of possession. In the face of otherwise all consuming fear, I felt power.

3.

Today I write from within an office in an academic institution at a desk upon which there is a box of 500 business cards that all identify me as Dr. Candice Wuehle. They have been there all year. I have not found a way to use any of them, for any purpose, other than reminding myself that I’m here.

It can be hard to remember that.

In this version of my life, those cards are a sort of self-portrait. Proof not of life, but of existence. Of existing.

4.

From behind my institutional desk I see there is some severe part of me that does not want to work. Some maladaptation. Some antique devotion that compels me to play the students in my ancient lit course a re-enactment of the vestal virgins burning; something that is gratified by reading aloud to them from Carson’s translation of Elektra.

You’ll be singing your songs/ alive/ in a room/ in the ground./ Think about that.

A sensation came to me as I was writing the Woodman poems. A faith that like a vestal, I am destined not for a job but for a devotion. That I am utterly my own master.

Alessandro Marchesini, The Sacrifice of the Vestal.

5.

When I was 17, I had a dream that Sylvia Plath came to me and gave me a white paper garment box. In it: a soft blue cardigan sweater and a set of pearls. Dream logic clearly dictated this as a direct order from my dead idol: become an artist.

I teach the students in the Ancient Literature class all about such visitations. Homer, who was instructed by a vision to deliver the The Iliad.

Sophokles, whose baldhead a passing eagle is said to have mistaken for a rock and concussed in an attempt to shatter the shell of a tortoise. Some scholars says this was how the playwright died, others say he interpreted it as a message to write.

For some, artists are always more alive when they are dead.

In general this is even truer for women.

6.

After I pass the doctoral exam I develop the first mantra of my life: You are an artist no matter what.

Mundane disappointments accumulate—I am rejected by hundreds and hundreds of teaching jobs, agents, presses, and literary magazines. With each disappointment, the mantra amplifies. I don’t even need to say the words aloud to feel them compress my energy, gather into an orb in my throat.

I say the words and I write the Woodman poems.

I read a brief entry from Plath’s journals that resonates so deeply it makes me cry. Regarding the Ariel poems, she writes simply: I am writing the best poems of my life. They will make my name.

After I pass the doctoral exam, I have one entire year to do nothing but make art. Around the time I name the manuscript Death Industrial Complex, a friend suggests I am not merely ambitious, but driven.

7.

DRIVE (verb)

To propel or carry along by force in a specified direction.

DRIVE (noun)

An innate, biologically determined urge to attain a goal or satisfy a need.

Other words people close to me have used to describe my relationship to my art:

MOTIVATED

CONSUMED

COMPULSIVE

OBSESSESED

POSSESSED

NARCISSISTIC

INSANE

8.

I put the following question on a quiz for the Ancient Literature students:

What does Elektra mean when she says, “I need one food:/ I must not violate Elektra.”

Answers vary. The closest to what I think is correct is something like, “Elektra means she has to stay true to herself.” The missing part of the answer, though, is that Elektra doesn’t have a choice as to whether or not she stays “true” to herself because Elektra is truth; alter that and Elektra is so disarranged as to not even exist. Carson’s diction—that bit of legalistic euphemy—in the word violate points towards intimate degradation; spirit rape.

This is exactly what I mean, though, when I tell myself I am an artist no matter what. To not be so is to not be.

9.

The events that will eventual lead to the President’s impeachment inquiry intensify around the time that Death Industrial Complex is accepted for publication. For a while now a surreal blur coats my life: not that nothing is true, but that truth means nothing.

I spend the autumn and early winter of 2019 reordering the book and writing its final poems. Johannes Göransson has suggested more “helter-skelter poems.” My computer mumbles news of the impeachment like a drunk friend—unbelievable, interminable, incoherent—and I scan the Google results of “helter skelter” “crime scene.”

Photos of the blood-writing, misspelled: HEALTER SKELTER.

Abigail Folger’s body on the lawn.

Glorious photos of Sharon Tate. Tan, bubble-haired, her waterline often rimmed in white to make her eyes appear as if she had even more window than the rest of us to look from.

Later on, the blurb for Death Industrial Complex will state that the book is “a meditation on the cultural obsession with the bodies of dead women” and I will think of the many hours I spent with my mother watching Unsolved Mysteries; of the teenaged summer I read Bugliosi’s book; of Manson’s command to his family, which I have unwittingly memorized: “leave something witchy.”

You can buy a pillow on Etsy upon which this phrase is cross-stitched.

The impeachment testimony mixes with the writing on the walls of the Tate and LaBianca homes as I write the final poems for Death Industrial Complex and I worry that there is no logic, no matter how sound or succinct, that can win any argument at the end of this decade. The skill of logic is at a low, the talent of imagination rare.

As a sort of antidote to Manson’s idea of witchery, it occurs to me that this is why the witches are in Macbeth. To prove that what sounds the most like sense is more powerful than sense itself.

As I continue to write the Woodman poems I have this thought: maybe, finally, poetry is going to win.

Sharon Tate in Valley of the Dolls (1967) Directed by Mark Robson.

10.

Part of the process of writing Death Industrial Complex was to see light like Woodman saw it, to visit the exact places she lived and photographed and to get as close as I possibly could to tracing the steps of her imagination; to seeing the ordinary she transformed into the extraordinary. Especially in her early photos, Woodman uses the Colorado landscape as a sort of gothic backdrop. The light is high and clear, the air thin. The hyper clarity of a psychic vision. Elektra-like, I suppose. To understand this, I drive into the mountains, park my car and just sit.

Although it is slightly rainy, with clouds hanging so low it sometimes feels as though I am actually inside of a cough of fog, Woodman’s aura never infiltrates the mountains. I wait maybe two hours before I admit to myself that the volt of insight I got from visiting RISD and the graveyards of Providence, Rhode Island is not going to electrify me here. I leave and as I round one of the severe bends common to mountain roads, a second atmosphere emerges. On the other side of the mountain, a mere half-mile from where I was parked, the sun has burnt through the stormy cloud cover. Several cars are pulled over. I follow the fingertip of a child pointing to the sky to see that there is not one, but two rainbows looped across the sky.

Is it kitsch if it’s really happening? I don’t know, but nothing could be less Woodman-esque. Yet, it is in this moment that I come the closest I have yet come to understanding her imagination: I see what it was like to live with the other side always right beside you, to have no reason to believe space is beholden to time, or bodies beholden to earth.

Western Colorado, 2019.

11.

You cannot read about Woodman without reading about her suicide at the age of twenty-two. Her father claims it was the receipt of a rejection from the NEA that prompted his daughter jump out of a window. In the same way that I don’t mention Plath’s suicide when I teach the Bee Poems, I never tell people this when I describe Death Industrial because I think it is a degradation to her work, an utter misunderstanding of what defined her. It invites one to read her as morbid, a sad girl, to see decay instead of invention. Death instead of creation.

There is a video taken by Woodman during the creation of the photo in the flour that details her artistic process, her care and intelligence and devotion. One of my favorite things in the entire world is the moment right before the camera cuts out, when Woodman looks into the lens and laughs, delighted, and in the voice of absolute joy states simply, “Oh, I’m really pleased!”

12.

Months after the book is published and in the world, I am still writing the helter-skelter poems.

These poems that began as an amalgamation of obscenity—a blood record of a murder merged with a moment in time that is itself the murder of records, a last gasp, a ghost trapped between the walls—but are now the origin of possibility, of imagination, of birth itself.

Female genius is often marked by humility, by restraint. Austen and the Brontë’s studies of manners, Dickinson’s small spaces and subtle rage, Woolf’s adroit tonality.

What I am saying is that for women, the difference between genius and insanity often hinges on having what some would call confidence and others would call bad taste: the ability to know not just know you are a genius, but to tell other people.

Me? I cannot even write the words I am a genius.

Woodman could though.

I think that’s why the poems of Death Industrial Complex won’t leave me alone, why it is a relief to admit I will never stop writing them. To continue to write is, at its most mundane, a way to keep Woodman with me like she is the ghost conjured to remind me that I am really here. I have not conjured Woodman, though. I suspect if I tried, she would not be that interested anyway. So to continue to write is, at its most profound, how I keep from violating myself. How I remember not that I am alive, but that in objection to the threat, condescension, and outright lies of which are the historical background in which the writing of this book exists, I am not only alive: I am an artist.

I can see forever.

I can look deeper and then deeper into the stuff the world is made of and I can keep looking for infinity.

Within myself, there is always more self. I insist on it.

This is, to me, the most important communication. The one you speak only to yourself. The language of the mise en abyme.

Candice Wuehle is the author of Death Industrial Complex (Action Books, 2020) and BOUND (Inside the Castle Press, 2018) as well as the chapbooks VIBE CHECK (Garden-door Press, 2018), EARTH*AIR*FIRE*WATER*ÆTHER (Grey Books Press, 2015) and cursewords: a guide in 19 steps for aspiring transmographs (Dancing Girl Press, 2014). Her work can be found in Black Warrior Review, Tarpaulin Sky, The Volta, The Colorado Review, SPORK, and The New Orleans Review. @glittertrash__