In quarantine, as in poetry, time is out of joint.

I have been thinking about Johannes’ post on the New Critics’ communication model, the “foreign sound” of the scream, and translation’s ability to perforate. Paul’s post about performance also brings up the idea of sound by citing Dominic Pettman’s “‘aural punctum’—a sonic prick or wound” that exceeds the normal boundaries of communication. Mark Fisher’s concept of “crackle” is another kind of aural punctum, a temporal short-circuit. In Fisher’s “The Metaphysics of Crackle: Afrofuturism and Hauntology,” he argues that the synthetic reproduction of analog noise in the music of artists like Burial and The Caretaker is a way of representing late capitalism’s damaged temporality:

“If the metaphysics of presence rests on the privileging of speech and the here-and-now, then the metaphysics of crackle is about dyschronia and disembodiment. Crackle unsettles the very distinction between surface and depth, between background and foreground. In sonic hauntology, we hear that time is out of joint. The joins are audible in the crackles, the hiss…”

I’m wondering how crackle might be applied to the lyric, which also has a disjointed temporality—an impossible voice, both present and not. I’m also thinking of Diana Fuss’ observation that “the corpse poem betrays a desire to wed itself eternally to voice, a voice capable of surviving death, a voice that conveys not a distant trace but a proximate presence.” I’m interested in a “poetics of crackle” that extends beyond musical forms, tingeing the supposed stability of the lyric with a halo of noise. What follows is my incomplete list of texts that crackle:

1.

Twin Peaks: The Return is a show about the failures of normal models of communication and chronology. We see this in the one-armed man’s refrain: “Is it future or is it past?” The series opens with a literal crackle: in the Black Lodge, where time is truly out of joint, the Giant tells Agent Cooper to “listen to the sounds.” We linger on a phonograph, which emits the scratchy, measured clicks of the needle at the end of the record. We’ve heard this sound before, when Bob possesses Leland Palmer in Season 1. This noise is beyond language; the Giant tells Cooper, “[i]t all cannot be said aloud now.” Other characters demonstrate this concept of unspeakable noise as well. In episode 3, Agent Cooper first encounters Naido, the eyeless woman whose voice is a radio squawk. Dougie Jones crackles too, in the sense that he can only speak through mimicry, repeating words or phrases that other characters say to him. Dougie’s mimetic speech situates him in the uncanny valley. Noise always signals a limit, and crackle is the indeterminate zone that is both/neither past and future, human and mechanical.

2.

Everywhere at the end of time is the latest release in The Caretaker’s extensive catalogue. Named after Jack Torrance’s character in The Shining, The Caretaker constructs his albums by looping and repurposing pop music from the 1920s with a thick veneer of crackle. Mark Fisher writes of The Caretaker, “The problem is not, any more, the longing to get to the past, but the inability to get out of it. You find yourself in a grey black drizzle of static, a haze of crackle.” The Caretaker has always been interested in representing memory loss in his music. Listening to Everywhere at the end of time creates a kind of active forgetfulness. Familiar-sounding melodies rise to the surface of the static, but you can never quite tell if you’ve heard them before or if they are just false memories.

3.

The famous ellipses in Chelsey Minnis’ Bad Bad warp the temporality of the poems, elapsing and deferring, signalling both a “distant trace” and a “proximate presence” at the same time. They are a kind of visual noise, durational but asemic, readable but unpronounceable:

“..the past used to be in the past but now it is in the aspen grove

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

…..as a combined unit of terrific imperfect parts……………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….”

4.

In Port Trakl by Jaime Luis Huenún (trans. Daniel Borzutzky), the speaker lands in a “gloomy and fictitious port” seemingly outside of time and space, “where everything ends / like a dream impossible to remember.” The crackle in this book appears in the fragments of Trakl’s language that infects the vagabonds stranded in this dream country: “I lost my language on the ashen / coast of Trakl.” Huenún also draws our attention to sound:

Wouldn’t it be better to listen to old songs

on gramophones molding with nostalgia—she asks.

Yes, it would be better to listen to your silly lyrics

with these wicked and happy

bar-drunks, he says.

5.

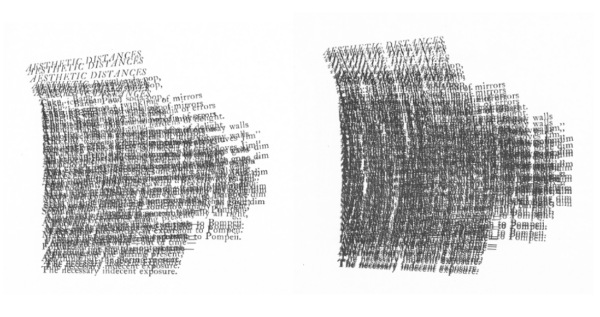

In Rosmarie Waldrop’s palimpsestic Camp Printing, single poems are printed multiple times on a page. The paper is manipulated with each impression so that a legible lyric poem becomes writing’s crackly ghost.

6.

Émigré by Genève Chao and Feeld by Jos Charles both challenge the idea that the lyric is monolithic and monolingual. Chao’s book is bilingual, written in English and French. Émigré places both languages on the same plane, so that neither is dominant and the reader must engage equally with both. The sense of crackle appears in the points of contact between the two languages:

to hâve

an outline

radieusea dazzlement

like reflets

or starscircle and

flit a

cintreall angles

and avarice

7.

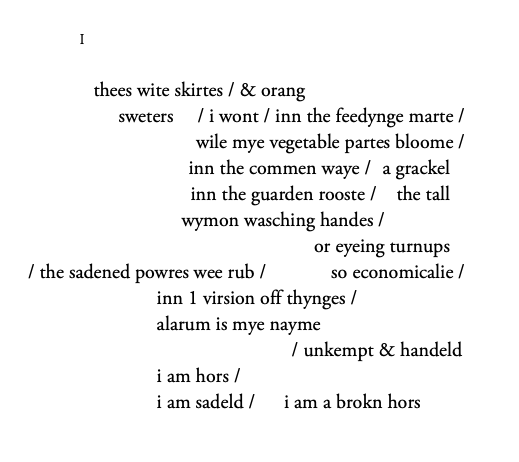

Similarly, in Feeld, Charles’ synthetic Middle English diction crackles with polysemy. Her innovative orthography makes us see and hear double:

8.

Hannah Weiner’s mediumistic approach to writing, represented in the formal arrangement of Clairvoyant Journal, reminds us that (for Fisher) crackle is a hauntological phenomenon. “We have unknown collaborators,” Weiner wrote in her script for her “World Works” performance piece. Clairvoyant Journal is a noisy text, with voices crawling across the page, voices encroaching on other voices until “IT WRITES ITSELF.”

9.

Paul’s post also mentioned Madison McCartha’s video work for Freakophone World. These video poems use vocal distortion, delay, and reverb in conjunction with typographic animations to explode the lyric. The project is explicitly hauntological: “Disinterested in traditional performances of black identity, FREAKOPHONE WORLD is a series of occult recordings, hauntings and invocations performing new black diasporic identities in an increasingly imperiled and globalized society.”

10.

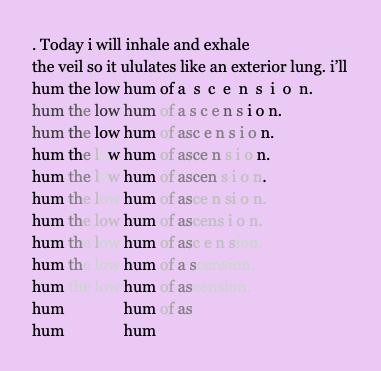

Jayme Russell’s recent post on Candice Wuehle’s book Death Industrial Complex describes the book’s “looping” and “doubling.” Paul also has written about Wuehle’s video poems, which “sound like they’re playing from an old and ghostly gramophone.” Wuehle’s poem “terrestrial” uses a combination of repetition and decay to simultaneously accumulate and disappear. As the text gradually fades out, it becomes a crackle at the edge of textuality, neither present nor absent. When the slow fade is complete, we are left with its noisy residue: a hum.

Zack Anderson holds an MFA from the University of Notre Dame. His book reviews appear in American Microreviews & Interviews, Harvard Review, and Kenyon Review. His poems have recently been published in Fairy Tale Review, The Equalizer, White Stag, and others. He currently lives in Athens, Georgia where he is a PhD student at the University of Georgia. @ZackAanderson