1.

Anne Carson: “I am interested in people who cut through things.”

2.

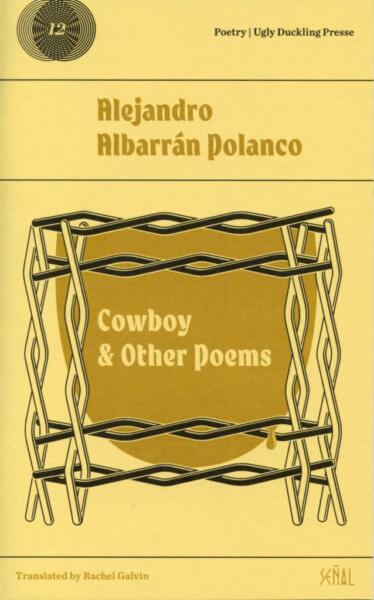

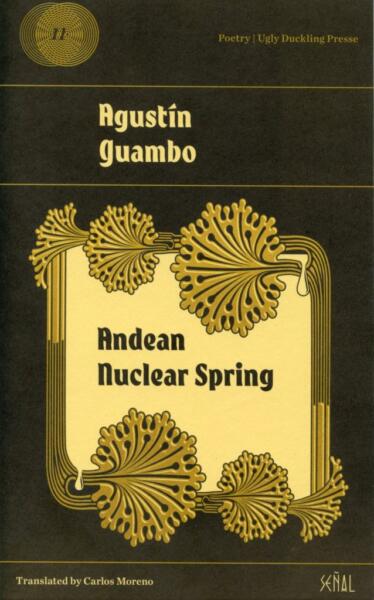

In my second post, I talked about a poetics of translation, of cutting through things, of poems that risk tearing themselves apart, of prophesy. In this post I would like to bring some of those thoughts back into this discussion as I zero in on a couple of recent chapbooks in translation: Alejandro Albarrán Polanco’s Cowboy & Other Poems (translated by Rachel Galvin) and Agustín Guambo’s Andean Nuclear Spring (translated by Carlos Moreno), both of which are part of Ugly Duckling Presse’s Señal Series of contemporary Latin American poetry.

3.

To bring things back to Anne Carson and the second post, Alejandro Albarrán Polanco is a person who likes to “cut through things.” In his chapbook Cowboy & Other Poems, Polanco repeatedly cuts through things, especially the human body. The poem becomes a cut-up field that is glued together and comes apart compulsively. In the titular poem “Cowboy,” Polanco cuts up the human body with a cut-up sensibility of vertiginous juxtapositions: “There are cables in the dermis.” This surrealistic juxtaposition creates an absurdly out-of-scale movement: “There are horses in the pubic.” It becomes a fantasia: “The raft on which I float is a stump and I’m riding it cowboy-style, riding my stump over the bile.” The surrealistic movement violently convulses inside and outside: we go from riding on a sea of bile to finding out that the stump is “far inside, in my stomach.” The poem is about a kind of violence, but it is also a kind of violence.

4.

Polanco’s poems create radical collages as they take on the violence of the world, creating the sense of what Joyelle McSweeney has called “ambient violence”[1]: the violence “reaches the speaker through media, including the media of his own and others’ bodies.” Apparent news reports of murdered women are cut into the text; visual pictures of how to make a bullet for a rifle interrupts the text. “Posthumous Instructions for My Body” is a poem in the shape of an instruction of what to do with the poet’s body (“First of all crush/all/the bones”) in order to teach a child to see “the value” in “the transformations,” that state where things happen – ie “the wound.”

5.

These poems are not just about violence and the body, but about the conflict between “transformation” and the static. While there’s a constant sense of violence – of cutting up, of tearing things apart – in order to make “things happen,” the static is, in a sense, much more violent. In the final poem, “Multitasking,” the poet tries to control the reader’s body (“why don’t you raise your head”), which may appear violent, but the reader’s inability to be moved is in service of a violent world: “Until you raise your head this isn’t going to stop.” These poems are beautifully convulsive: the cut-through things, but in cutting they create a visionary vista. In Bonney’s words, these are poems at risk of tearing themselves apart. In Berg’s words, they make space for something “truly new” to “take place.”

6.

Another recent title in Ugly Duckling Presse’s crucial Señal Series, Agustín Guambo’s Andean Nuclear Spring, translated by Carlos Moreno, is also driven by a montage sensibility. There is a feeling of the poem as loops that have been sutured, often in a way that leaves the wounds/cuts visible:

the remnants of an Andean constellation kissing the skin of rhinoceri-

the remnants of an Andean constellation kissing the blood of rhinoceri-

the remnants of an Andean constellation kissing the ashes of rhinoceri-

the remnants of an Andean rhino kissing the blood of constellations-

Guambo’s poetics is largely generated by repetition – often less foregrounded than this example – that often gains its energy based on minute variations.

7.

As the title of one poem reveals – “a reading from the book of the andes or the song of the indigenous scar” – the wounds that proliferate in this book lead back to the great atrocity of colonial violence, invoked in the poem “[iii]”:

Year 5522 I remember the archeology of insects I remember I remember the anthropology of birds. I still remember the silence of the sea foam breaking against my chest I remember the Andean city where we left our shadows burnt where rhinoceri wander but none of them knows about our names nor about our prehistoric blood flooding the trees.

One ingenious detail in this litany is the way the “prehistoric blood” is in present tense flooding the trees. We might expect the blood to have taken place in “prehistoric” times, but it’s the blood that’s prehistoric, the wound is still open. It cannot scar over.

8.

Throughout these poems, languages interpenetrate. The original Spanish poems are shot through with phrases in indigenous Kichwa as well as English-language pop culture detritus; the English translations are cut through with both Spanish and Kichwa:

the skull of the sea shines in the Andean páramo

in the middle of a pack of trees an arcane song

announces the birth of night

– pampachamuni – apullay uyahuanquichu, manachu? –

The book is a dynamic, looping wordscape, in which foreign languages make wounds.

9.

In his translator’s afterword, Moreno begins his afterword to the volume by declaring “The work of translation will always entail and generate spaces of fragility.” This fragility comes out of “all the possibilities a restless mind might encounter in each word.” The translation reveals a vulnerability of the text, a vulnerability where languages mingle, where possibilities proliferate. To go back to my very first blogpost on interlingualism, translation – in bringing languages into contact – creates a kind of multi-directional wound.

[1] McSweeney, Joyelle. “A New Quarantine Will Take My Place, or Ambient Violence, or Bringing it All Back Home”:

Johannes Göransson is the author of four books with Tarpaulin Sky Press — Entrance to a colonial pageant in which we all begin to intricate (2011), Haute Surveillance (2013), The Sugar Book (2015), and Poetry Against All (2020) — in addition to three previous collections of poems: A New Quarantine Will Take My Place, Dear Ra, Pilot (“Johann the Carousel Horse”) He has also translated several books, including Aase Berg’s Hackers, Dark Matter, Transfer Fat, and With Deer as well as Ideals Clearance by Henry Parland and Collobert Orbital by Johan Jönson. @JohannesGoranss