The following is three Action Blog contributors’ reactions to excerpts from Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg’s One Last Trip to the Underworld:

(FYI: today is the last day to watch these films on Art21.)

Paul Cunningham:

I focused on the first three videos being streamed via Art21.org.

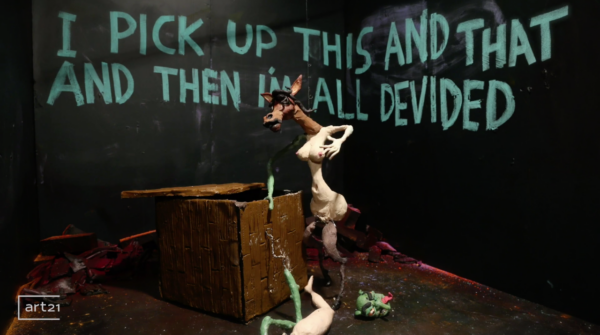

Instantly reminded of Hans Bellmer’s dolls as these disembodied limbs leave the crate, attempting to reanimate, eventually forming a monstrous hybrid/grotesque assemblage. The Middle English spellings of “untill” and “devided” are interesting. The emphasis on the prefix “de-” puts Djurberg and Berg’s excess into conversation with “decline” – which reminds me of the relationship between 1890s decadence and sickness. Djurberg’s excess is also tied to natural disasters (volcanoes, earthquakes). Such decadent excess is also prevalent in This is Heaven. Additionally, both films share pig bodies in common.

More on sickness: a woman keeps flashing on the screen, interrupting this assemblage’s animal/drag performance. If you pause, the woman is writhing in a padded room.

It appears she has been institutionalized. There are pink curtains in the padded room and the pink matches the color of her lips and her nipples. I wonder if the crate of limbs and the assemblage are this woman’s fantasy? The skull with the Pinocchio’s nose (along with the writing on the walls) might insinuate that the body is false. The woman in the padded room seems more excited by the assemblage – she is writhing around on the floor and caressing herself. The assemblage sometimes resembles a clown, sometimes wears a judge’s wig (or peruke). Both of these elements (clown and judge) return in How To Slay a Demon. The assemblage grows more sick when it wears a strap-on dildo. This new phallus results in “collapsed lungs” and a stopped heart. When the assemblage holds its tail, it runs parallel with the strap-on.

Incredibly voyeuristc. Reminds me of the terrifying POV shots near the end of Rosemary’s Baby. Three different human female bodies, outfits: clown with round buttons versus wolf; gold spandex versus demon (?); peacock robe versus what appears to be another demon; there’s also a woman in a pink-white dress being pinched and fondled by a mandrill monkey. (The use of the peacock felt very intentional because of a peacock’s ocelli.) We cycle in and out of these POVs via blinking, which grows more and more rapid as the film progresses.

Pigs feel like positive things. Celebrations of what has been censored (sexuality) or the abject (a mother pig’s milk). The woman who is trapped in the padded room of Damaged Goods appears to fantasize about taking many forms, becoming many parts, trying to rebuild – adding a curvaceous pig’s bottom to its already round bottom. Becoming more excessive, refusing to be censored.

The demon-like male creature in This is Heaven, who wreaks havoc on wildlife and whose ‘success’ is built on lies, appears to be finally punished for his domineering ways. He should not have drank the pig’s milk.

Madison McCartha:

I’m reminded of the self-reflection described in Kristeva’s Black Sun. With Djurberg’s films, there is an erotics to self-regard, to what Kristeva describes as melancholia’s obsession with the loss of an imagined, alternate self, one embedded in another dimension, an “imagined sun” impossibly “bright and black.” I think this plays out in different ways across each film, but Kristeva might speak most directly to One Last Trip to the Underworld…

In Heaven, I am wounded by the score, by the near-feral demon captor, and in the way the eyes take in the diamonds it seeks to possess, in the way the demon’s eye golds – not just reflecting but becoming itself the object desired. Here the gaze takes on an antic transmutation.

I wonder if there’s a relationship between this antic self-gilding-eye, the violence enacted on its behalf, and the self-assembling body in Damaged Goods? Maybe not.

What does it mean to put a self together in a room of parts? To assemble a “my” in a room of dispossession? This assemblage implies an unseen violation, a disassembly, except when does this violent dismemberment occur, and how does it relate to the footage of the prone figure, naked, exposed yet ecstatic in her padded room, in the institution of the image?

Here there might be a relationship between the intercutting flashes of this footage, and the exposed wire-frame joints, the nerves that link together the assembled body…

I also see here a kind of virtual poetics – where duration forces one set of images (or ream of footage) into a subordinate position to the other. I’m thinking about the politics inherent in virtual reality – that there is a real world and a subordinate virtual world.

Is there a connection between this effect of virtualization, between this virtual-world and the under-world which penetrate the surface of Djurberg’s films?

With How to Slay a Demon, what does this penetrative virtual world accomplish? And what power do we have over it?

The POV [as Paul points out] feels continuous with this discourse on the virtual. If virtual technologies function, we often say, as “empathy machines” (2), what happens when we lose control, as we do in Djurberg’s films, of the arching neck, of the unfolding scene this virtual eye blinks (us) between?

Here the power is exerted over the user, but in How to Slay, as with other films by Djurberg and Berg, I’m not yet sure what to make of these feral simulacra, these surrogate selves (or surrogate parts) standing in for the desires by which these human figures are possessed. It’s difficult for me not to see also the demon sitting on the maiden’s chest in Henry Fuseli’s 1781 painting, “The Nightmare” – most recently purchased form a New York dealer in 1955 by the Detroit Institute of Art, where it now resides. (3)

—-

From Dodie Bellamy’s comments on Diane di Prima – on the subversive potential of becoming the ‘nightmare’ – we can see how Djurberg’s films are charged with similar stakes. What are the stakes? As with the demon in Fuseli’s painting, the nightmare refuses to move, and so I see these artists as finding ways of composing with the nightmare – with addiction or depression – instead of trying to write around it.

What’s missing both in Bellamy’s account and Djurberg’s recent exhibit, however, is race. In earlier films from Djurberg, the shame she describes, that saturates her work, takes up the shame embedded in the relationship between film’s multiple I’s and the racialized body – a relationship tinged, these films tell us, with violence and complicity.

Those early films deliver a double wound, for me, one that has frustrated me (with their racism) as much as it has shown me the volatile affective space Art might occupy. A space that has racial politics.

I’ve previously written about the black bodies in these films, and the subterranean association I see between them and the factory workers in Detroit (where I was born). I am most moved in those pieces (puppets from The Parade of Rituals and Stereotypes) by the ways the ambivalent often brutal violences enacted on these black plasticine figures results in an opaline spill, what I call a violent affect fluid, that both resists categorization and breaks the spell (in many ways) of the world-space itself.

In this exhibit, Djurberg doesn’t deploy this fluid to express a world-shattering, categorically unstable violence, but I wonder if the key is instead in the POV blink, the flash, or this flickering filmic surface.

For me, the power dynamic between art-object and audience, or between user and interface, can always become racialized. If racialization, as Ruha Benjamin points out (in Race After Technology), is the experience of being encountered as a surface, what do we make of the textural surface evinced by these plasticine puppets? By these films? Or by the medium itself?

2 – https://www.wired.com/brandlab/2015/11/is-virtual-reality-the-ultimate-empathy-machine/ ; http://beanotherlab.org/home/work/tmtba/

3 – dia.org/art/collection/object/nightmare-45573

Jayme Russell:

I’m interested in the portrayal of female bodies and how the camera is used to show those bodies. In both Damaged Goods and How to Slay a Demon the viewer is voyeur. In Damaged Goods, a woman is sensually rubbing herself against the floor. Her onscreen positioning makes me think of cybersex. Her naked body dominates the room, all of the furniture looks small in comparison. Her body is the focus. The title insinuates then that she herself is damaged goods and the box full of parts makes that idea literal. A nude torso with one leg appears first from the box and begins trying on parts. Paul suggests that the scenes of assemblage may be the woman’s fantasy. I think this is true, especially since we only see the whole woman in flashes that build to a climax, but I think that all these attempts at putting together parts to form a body is there to fulfill the desires of the audience, as well. Certain body parts don’t work. Certain parts are funny. Certain parts, like the big ass, seem to be pleasing. This reminds me of the female body in music videos. Something like Doja Cat’s “Cyber Sex” is a perfect example of audience as voyeur, as well as how the female body is often thought of as a Western ideal: skinny waist, big bust, bare ass. At times, the female body in the music video is in the same position as the body in the film. Finally, the fantasy ends when all of her limbs are ripped off and her heart stops, as the subtitles say. She then stops writhing on the floor.

In How to Slay a Demon, the first shot we see is from a clown’s POV. It is lying prone and looking down at its body. The shot is sexual, because we cannot see the face and the body seems so close to the camera. The clown’s suit has a very rich texture and bold colors and makes noise when touched. Suddenly, the same shot is used as the body of a woman in gold takes the place of the clown. This female body looks pregnant and an animal claws over her stomach. Other bodies are seen through this same POV, some with open legs. Demons and animals scratch at and pinch the bodies. The audience takes on the woman’s POV but somehow, seems detached from the women. They aren’t being forced into sexual encounters with the animals and demons. They seem to welcome it, even though they may not like being pinched. In the end, there is a trick of POV when the clown is seen in front of the woman, instead of being situated in the first person POV. It’s unexpected. Although both short films are about sexual fantasies, they have different tones, set by the music. How to Slay a Demon seems much darker because of the repetition in the music, as well as how the animals and demons interact with the bodies. Movement in Damaged Goods is jerky and somewhat comical. Characters don’t really interact, whereas the smooth caressing of the bodies in How to Slay a Demon are uncomfortable.

Paul Cunningham is the translator of Helena Österlund’s Words (OOMPH! Press, 2019). He has also translated two chapbooks by Sara Tuss, Efrik: Automanias Selected Poems (Goodmorning Menagerie, 2016) and The Night’s Belly (Toad Press, 2016). His creative and critical work has most recently appeared in Snail Trail Press, Kenyon Review, Quarterly West, Poem-a-Day, DIAGRAM, and others. He is an associate editor of Action Books, editor of Deluge, co-editor of Radioactive Cloud, and co-curator of the Yumfactory Reading Series. He is a PhD candidate at the University of Georgia. @p_cunning

Madison McCartha is a black, queer multimedia artist and poet whose work appears or is forthcoming in Black Warrior Review, Denver Quarterly, The Fanzine, jubilat, Prelude, Tarpaulin Sky, and elsewhere. Their debut book-length poem, FREAKOPHONE WORLD, is forthcoming from Inside the Castle in 2021. Madison holds an MFA from the University of Notre Dame and is a PhD student at UC Santa Cruz. @MadisonMccartha

Jayme Russell is the author of two chapbooks: Pinkification (Dancing Girl Press) and Pink Poems (Adjunct Press). Her work has most recently appeared in Cream City Review, Pleiades, Heavy Feather Review, and elsewhere. She received her MA from Ohio University and her MFA from Notre Dame.