Do I personally attend to sound in an aural space? Do I read in “poet voice”? Do I verbalize my poems’ most sonic qualities? These are all questions we might have asked ourselves at one time or another. A contemporary poetry reading (virtual or IRL) should at least attempt to intoxicate, not anesthetize. I know Zoom poses certain limitations, but – back when we were still doing the IRL thing – I have absolutely dozed off during poetry readings (and I don’t blame myself). A poem read silently on the page might not be boring, but what happens when a poet doesn’t appear to know how to read that same poem aloud? Perhaps a question to ask ourselves is: Does my relationship with my own poems lack intimacy?

In Dominic Pettman’s Sonic Intimacy, the author suggests that a voice “has the potential to create a glitch in the humanist machinery, when it surprises us with the intensity or force of an ‘aural punctum’—a sonic prick or wound, which unexpectedly troubles our own smooth assumptions or untested delusions.” As poets, isn’t this what we should be striving for? If you’re voluntarily reading your work to a live audience, shouldn’t you want your voice to sound wild, unmediated like, say, poet-medium Hannah Weiner? Or elongated and unnatural like Bruno K. Öijer? In Monday’s blog post – “Formal Contortion and Two-Way Distortion Between Poet and Performance” – Jace Brittain asked an intriguing question about reading versus performance:

What makes these performances (or any poetry reading, obviously) engaging and memorable? I don’t know whether I intend to make a distinction between performance and reading, but I do see something unique in Öijer’s work—the performance seems to get at something that both is and isn’t in the text (I almost want to say it isn’t just a reading). Why do Öijer’s performances and written poems seem both separate and yet inflect upon each other in such interesting ways?

I do intend to make a distinction between performance and reading. I think there’s a clear difference. I think as soon as any poet or critic begins describing a “style of reading” they are tapping into something more performative.

I’ve also been thinking a lot about last week’s post from Johannes on occult ekphrasis and the part of Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty where the author suggests making language more spectacular, giving words “something of the importance they have in dreams.” I think of some of my favorite poetry readings when I read Artaud’s description of spectacle:

Cries, groans, apparitions, surprises, theatrical tricks of all kinds, the magical beauty of costumes taken from certain ritual models, dazzling lighting effects, the incantatory beauty of voices, the charm of harmony, rare notes of music, the colors of objects, the physical rhythm of movements whose crescendo and decrescendo will blend with the rhythm of movements familiar to everyone, concrete apparitions of new and surprising objects, masks, puppets larger than life, sudden changes of lighting, physical action of light which arouses sensations of heat and cold, etc.

Candice Wuehle has been sharing recordings of herself reading poems like “telephone scatalogia/gothica” and “waxed” from her new book Death Industrial Complex, but they sound like they’re playing from an old and ghostly gramophone. This really adds to Johannes’ post responding to two recent reviews of the book:

[…] by naming her poem after Woodman’s photograph, Wuehle makes a double of the self. In his review of the book in the journal Empty Mirror, Tom Snarsky argues that what Wuehle’s doing is closer to “cloning.” I like how in both of these responses (Snarsky and Corrao), the reviewers describe a poetry that doesn’t follow the communication ideal, but rather follows a gothic logic of doubling. Wuehle doesn’t see then recreate, depict.

On the one hand, we have Candice Wuehle – the poet. Through occult ekphrasis and the creation of these ghostly recordings, we receive a signal from beyond. A second Candice – a double – who, through occult ekphrasis, helps us to read from a doubled position: Francesca Woodman.

Like how when i located the missing girl i knew here name was Double.

Like a mirror is not a weapon.

Like i had never locked smallest fingers with another girl and sworn to stay

just exactly the same.

In the same way ghostly voices would interrupt during a Hannah Weiner reading, the reader of Death Industrial Complex might gradually begin to believe they are receiving transmissions from the dead. It might even be fitting to describe occult ekphrasis as a translation of the dead.

Valerie Hsiung is another memorable performer. I recently saw her give several readings from You & Me Forever. At multiple off-site events I attended while in San Antonio, Hsiung would make sudden movements and direct eye contact with spectators during her readings. Such an intense and intimate performance might even make readers feel implicated when Hsiung addresses the “You” of You & Me Forever:

If you didn’t do anything then why would you be worried? would you be scared

You can think whatever you want…

About me… The people… I cared about.. And you can think it’ll get to me somehow… That you’ll get what you want… Out of me…But you’ll never

never changemy mind…

Many of the off-site venues didn’t have stages, but Hsiung needs no stage. Again, when thinking of Hsiung’s own stage-less theater of action, I am reminded of what Artaud says will happen if we “eliminate” the stage:

A direct communication will be reestablished between the spectator and the spectacle, between the actor and the spectator, because the spectator, by being placed in the middle of the action, is enveloped by it and caught in its cross-fire.

Typically, Hsiung would already be sitting down at a random table when she would begin her reading – sometimes sitting across from someone she knew or someone she didn’t. Eventually Hsiung would carefully stand up with her book and slowly approach different spectators. If there was chatter in the bar or restaurant, you could literally hear its volume drop as Hsiung began her performance. Male audience members typically looked nervous when she approached them, not knowing what to expect from this mobile poet. This is precisely why I love Hsiung’s reading style. Because her audiences are at her mercy. She becomes the room and we are enveloped by her poems, caught in the cross-fire.

The poet is in control.

*

Additionally, an already engaging performative voice might only be further enhanced by added theatrical or visual effects (i.e. masks, costumes, voice-altering devices, animal calls, projections). I think a “mask” can be many things and none of those things should necessarily be considered false. Think of the “mask of art” as a doubling of your poetry’s potential. Perhaps your poem, your mask, can even be a threat to a homophobe, a racist, a chauvinist pig etc. Whether you mask your voice or your face (or write in a persona), I believe the overall affect can only be heightened. I think Joyelle McSweeney says it best in The Necropastoral: Poetry, Media, Occults:

“[…] the Mask does not conceal an authenticity but insists on a doubleness, a nonidentity in the circulation of signs. Looked at another way, if power requires mimicry, a subject of difference that is almost the same, but not quite, and realism as a photographic genre is a compulsory mimicry of the regime of the ‘real’, the Mask of Art widens this aperture, amplifies the ‘not quite’, creates a chaotic antirealm that claims the city for Art. The city is stamped with Art. It is wounded, punctured by Art. It is posed and punctured with a junkie’s needle. It swoons. It takes the Drug of Art. It wears the Mask of Art.”

Don’t just read your poems, perform them. Consider also how you could fuse the landscapes of your poems with your ideas of selfhood. When it comes to pop music, musicology lecturer Adam Harper writes, “No longer is the voice merely a figure in the landscape, but it fuses with the landscape.” In other words, we should be intimate with our poems and become their landscapes. Perform, sing, and scream the trees, the pollutants of our poems!

Finally, here are some recent performances I haven’t been able to shake from memory:

When attending a reading at La Villita Café in San Antonio, I was wowed by the poems of DJ Ashtrae (aka Joshua Escobar) as well as the queer tangles of his tubular mask. At the Letras Latinas Blog, Escobar has previously discussed why multiple pronouns are used in Caljforkya Voltage: “Is this a chronicle masked as art? What do we make of a voice that isn’t easy to locate? I hope my work raises these questions before it can be typecasted or dismissed.” Similarly, the notion of “voice” or “body” might be difficult to locate in Wuehle’s Death Industrial Complex.

Escobar’s first full-length book of poems – Bareback Nightfall – is forthcoming from Noemi Press.

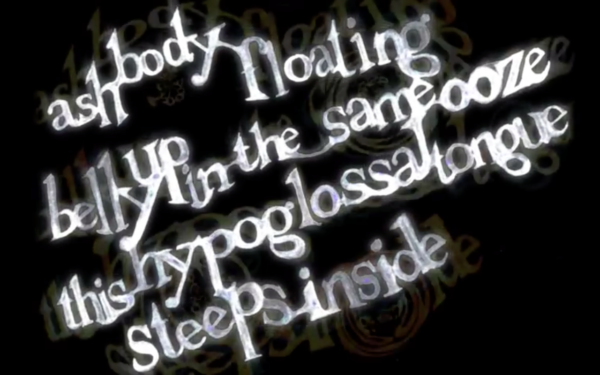

Fellow Action blog contributor Madison McCartha gave an exhilarating reading from his forthcoming Freakophone World (Inside the Castle, 2021) at the 2019 &Now Conference. Note how he alters his voice alongside his video poetry. (You can read Madison’s most recent Action blog post here.)

To promote Ready for the World, Becca Klaver has been giving witchy readings live on Instagram where she applies different filters to her face. Follow her project here.

*

Shouldn’t we all want to perform our poems to make spectators’ perceptions “glitch” in new ways? Ways that are humanly and conceptually baffling? Don’t you want your poems, on and off the page, to re-shape the room? Take control? Poetry can be your force.

Your frontline. Your weapon.

Paul Cunningham is the translator of Helena Österlund’s Words (OOMPH! Press, 2019). He has also translated two chapbooks by Sara Tuss Efrik: Automanias Selected Poems (Goodmorning Menagerie, 2016) and The Night’s Belly (Toad Press, 2016). His creative and critical work has most recently appeared in Snail Trail Press, Kenyon Review, Quarterly West, Poem-a-Day, DIAGRAM, and others. He is an associate editor of Action Books, editor of Deluge, co-editor of Radioactive Cloud, and co-curator of the Yumfactory Reading Series. He is a PhD candidate at the University of Georgia. @p_cunning