1.

Whether on the page or as a poem-film, followers of Action Books really seem to love this poem by Bruno K. Öijer:

we were the last

to leave every party

and we had nothing

but our young faces

the world was sick

sick and shut down for a thousand years

red neon fell like embers

the streets ran black

and I don’t know what it was worth

or if anything survived

but it stuck to our clothes

stuck to our hair

and we haven’t come home

it’s a lie that we’ve come home

we’ll never come home

none of us will ever come home(from The Fog of Everything of The Trilogy, 202)

I think it has something to do with the fact that we’re all locked down in quarantine. I keep thinking about how quarantine has disrupted our notion of ‘home’ and this passage from Jace Brittain’s post from a couple weeks ago:

“Things only really become unheimlich for the reader with the odd repetition of Hem / home and the revelation of the doubled account of the poem that exists against “a lie that we’ve come home.” The two accounts unsettle the reader’s notions of the poem’s present.”

Our present conception of time has been deeply distorted. I think that’s why I keep thinking about the Öijer poem. If and when things go back to normal, is a return to familiarity really possible? The new normal might be unheimlich for a while. Things might never be the same. The idea of a “return” also reminds me of Zack’s post on Monday where he wrote about time “out of joint,” a poetics of “crackle”, and Twin Peaks: The Return:

“I’m wondering how crackle might be applied to the lyric, which also has a disjointed temporality—an impossible voice, both present and not. I’m also thinking of Diana Fuss’ observation that ‘the corpse poem betrays a desire to wed itself eternally to voice, a voice capable of surviving death, a voice that conveys not a distant trace but a proximate presence.’ I’m interested in a ‘poetics of crackle’ that extends beyond musical forms, tingeing the supposed stability of the lyric with a halo of noise.”

2.

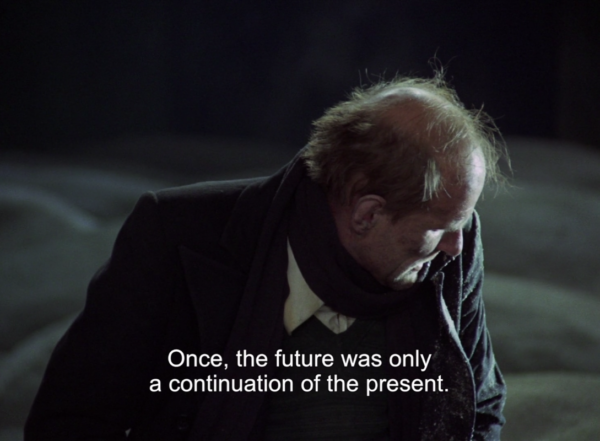

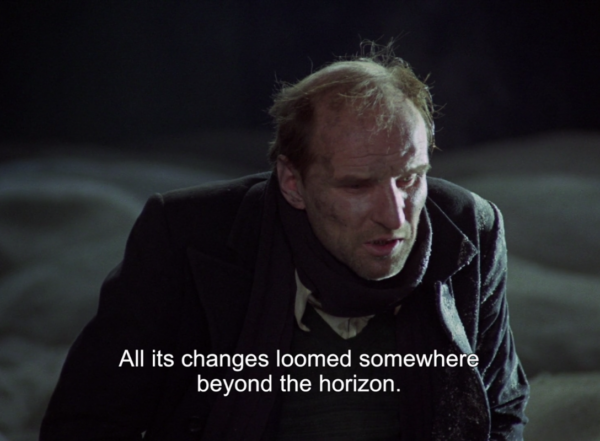

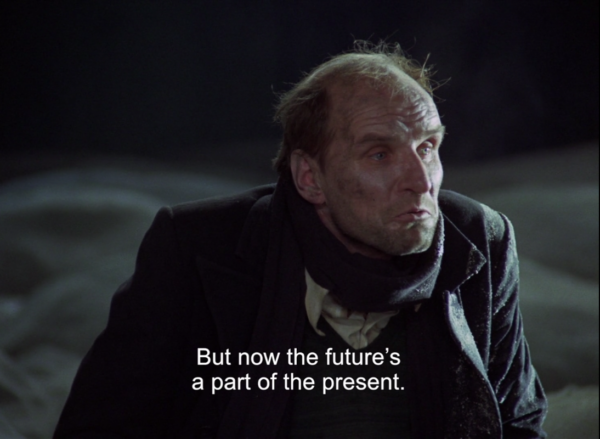

“But now the future’s a part of the present.” This is what the guide says when he and his group reach the toxic, radioactive belly of the Zone in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979). The same Zone (aka Tallinn, Estonia) that most likely gave Tarkovsky the cancer that would kill him in 1986.

In his latest book, Poetry Against All: A Diary, Johannes writes:

“I read poetry for the ruins because they reminded me of Stalker, where the guide brings customers into the Zone, which may be the area infected by a toxic disaster or may be the Zone of Art, where every desire can come true. The guide’s hair is gray in tufts and his child was born misshapen because he has spent too much time in Art’s evil zone; it is has made him an outsider in his town, a foreigner in his own family. Art affects the body like cancer. Home is where your heart is, homesick is what your heart is. What evil it is to be so saturated by art’s strangeness.”

Now, in quarantine, our only future is the present. “Decadence” – decay – decline – a declyining – cadēre – a fall.

Zack’s post reminded me of the very last episode of Twin Peaks. Where Dale Cooper looks at – an alternate version of Laura Palmer? – as if he’s just had an important realization, and asks, “What year is this?”

It feels like we’ve been falling for a while now.

What year is this?

De- is our new de-fault mode.

What month is this?

We are Decadent again.

What day is this?

2.

My own poetics is perhaps located somewhere between what Joyelle once called New Decadence and an anthropogenic literary imagination similar to what David Farrier describes in Anthropocene Poetics:

“[…] I follow the prompting of Neimanis and Walker to explore the thickening of the present as a point of confluence between deep pasts and deep futures. This viscosity – devolved across species and objects, as well as the divisions of place, time, culture, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and capital that carve up the anthropos – is the basis for a new and necessary imaginative project, a world-making for the Anthropocence, in Deborah Bird Rose’s sense of becoming with others, and of Earth itself as a work-in-progress. Intimacy allows us to imagine worlds of possibility; whether in terms of texture, sensuality, or violence, intimacy achieves a form of knowledge in the traffic between entities” (19).

I feel like I have a deeply intimate understanding of my mortality (maybe it could be called a thanatopic intimacy) when it comes to our ailing, carved up planet. Lodged in the present, I feel like a Decadent in the same way some artists think of themselves as avant-garde. Not in the historical sense obviously. The ‘avant-garde’ is not necessarily a historically fixed phenomenon and I believe the same is true of Decadence. Ideologically, the Decadence of those arsenic-yellow 1890s feels reminiscent of the Graveyard Poets of the eighteenth century. I feel like all of these things – a Decadent, a Graveyard Poet, etc.

And what about the Gothic?

For instance, is Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray a Decadent novel or a Gothic novel? The distinction doesn’t really mater to me and I appreciate that the lines get blurred. I believe the Gothic is an ancestor of Decadence. Either way, excess lives on. Undead. Zombie-like.

I appreciate, most of all, that Decadence was not planned or born out of an institution. It came without instructions or a formal rubric. It was something viral, contagious.

You just wake up one day and suddenly – like it or not – you’re wearing a Mask.

3.

“At any rate, it is a very queer new sort of quarterly.” Critics were outraged by the Decadence of The Yellow Book and Aubrey Beardsley’s illustrations were often described as grotesque and pornographic. In an 1894 issue of The National Observer, an anonymous critic resorted to using medical terms to criticize the “hyper-sebaceous” and “fatty” Decadence of the third volume of The Yellow Book:

“The truth is that Mr. Beardsley scorns to picture any person who is not suffering from xanthelasma, which is defined in medical books as an appearance ‘caused by hypertrophy of sebaceous glands and fatty degeneration of the subcutaneous connective tissue.’ This extreme xanthelasma is the reason that Mr. Beardsley’s figures are attenuate where you would expect plumpness, and sebaceous where you would expect them to be slim. Mr. Max Beerbohm’s caricature of George IV. is also hyper-sebacious: it rather resembles a study in viscera. The ‘note’ which accompanies it is not quite clear to the ordinary intelligence. But that is because Mr. Beerbohm’s intelligence is not ordinary.”

Exactly. Art that is “hyper-sebaceous” or “fatty” – too much – is always a threat to the “ordinariness” of the poetry establishment. My grotesque and bilingual Swedish-English poems, for example. A collection of these are forthcoming from Schism Press later this year. More about that in a future post…

4.

I think many Victorian studies scholars have been puzzled by my desire to link Decadence to an ecopoetics because we usually associate ecological awareness with ‘progress’ or moral ‘progressive’ acts, but when we think of Decadent characters in fiction, we often think of villains (i.e. a blood-sucker like Dracula or the wasteful Eugene Wrayburn of Dickens’ Our Mutual Friend). Characters who have gone too far. Obscene, tasteless excess.

Impurity. Evil. Chaos.

The Zone of Art.

Mondo Trasho (1969) Directed by John Waters.

Maybe my own queerness is the truest of crimes! Maybe a queer is always-already gossip! Maybe when I translate new poems into English, my threat level rises! Maybe I love when my threat level rises! Maybe I’m a threat to the “gold standard“! Maybe just maybe my bilingual poems, my camp, my puns, my gore, my excess. My poetry is my weapon. The kind of weapon I wrote about in my first post. The kind of weapon that Audre Lorde has described:

“I am here because I am greedy, and curious. I believe I am an endangered species the same way each of you is endangered, and poetry is a weapon” (Conversations with Audre Lorde)

Maybe Queerness and Decadence go hand in hand.

In the Decadent scriptures of Huysmans’ A rebours, Des Esseintes recalls the “cherry lips” and “hips” of his male companions. I think we can learn a lot about Decadent appetites from the excess of A rebours. And we can definitely learn a thing or two about Huysmans in Robert Baldick’s biography. Here, an 1890 letter from Huysmans to Raffalovich:

“Your letter and your book bring back to mind some horrifying evenings I once spent in the sodomite world, to which I was introduced by a talented young man whose perversities are common knowledge. I spent only a few days with these people before it was discovered that I was not a true homosexual – and then I was lucky to get away with my life […] Never in my life have I seen anything so sinister.”

A few days?

5.

Interestingly enough, Regenia Gagnier has written about Decadence as a form of “progress”:

“Progress was decadent because increasing individuation led to the disintegration of the whole. In similar formulations, moral character, as the alignment of individual development with the goals of the state (what we now call governmentality) was precisely what Bohemians – both soft Bohemians such as Bloomsbury and hard Bohemians such as Verlaine or Jarry – resisted.”

Gagnier’s idea of a disintegrating “whole” comes from Nietzsche’s 1888 essay, “The Case of Wagner: a Musician’s Problem”:

“What is the sign of every literary decadence? That life no longer dwells in the whole” […] “The whole no longer lives at all: it is composite, calculated, artificial, an artifact”

This echoes Johannes’ thoughts above on ruin porn (“I read poetry for the ruins…”).

The whole – aka society – was/is still sick.

We were sick whether this pandemic happened or not.

This is why many of us continue to make art.

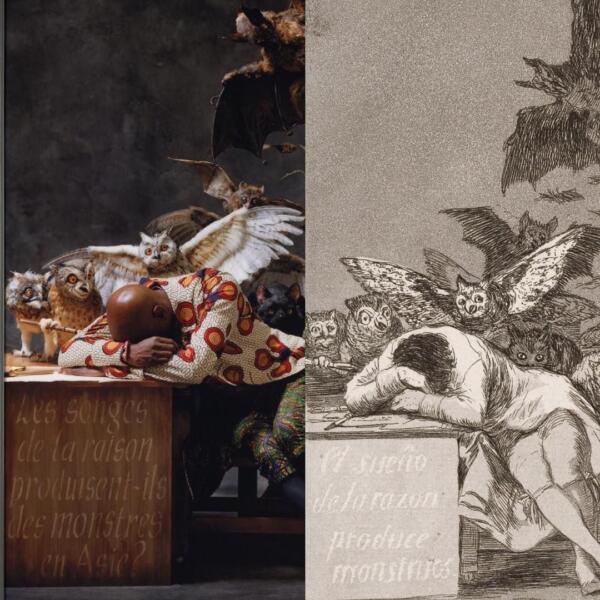

Yinka Shonibare’s The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (Australia). 2008.

6.

A self-described “trojan horse,” the excess of Yinka Shonibare MBE represents the blurred lines of Decadence and the Gothic – or even the Decadence of the Gothic. Shonibare’s Decadence in particular has been called “postcolonial Decadence.” Whether Shonibare’s work is reimagining significant moments of Britain’s colonial history in vibrant African-Dutch-Indonesian patterns, or inserting himself into The Picture of Dorian Grey, Shonibare’s excess is infectious and unapologetic in its restagings of Rococo artworks, Italian opera, Wildean antirealism, and more!

Above, in his reimagining of Goya’s The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, the specter of unreason haunts five different sleeping figures across five different continents. It reminds me of what James Pate writes in Flowers Among the Carrion:

“In the Gothic, we are no longer placed on a pedestal above other phenomena due to History or God or Nature. In the Gothic, we are small beings under the night sky, limited in our knowing and capabilities. There is always a House of Usher or a planet called Melancholia to remind us of our finitude” (3)

Quarantine feels like haunted sleep. We think we wake up to the news and coffee each morning, but it’s just more retweets of the same irrational nightmare.

The same sickness. It never goes away.

What day is this?

7.

Maybe the future was never a continuation of the present. Maybe it was a contamination of the present.

8.

we were the last

to leave every party

and we had nothing

but our young faces

Maybe we are Decadent again.

Paul Cunningham is the author of The House of the Tree of Sores (Schism Press, 2020) and the translator of Helena Österlund’s Words (OOMPH! Press, 2019). He has also translated two chapbooks by Sara Tuss Efrik: Automanias Selected Poems (Goodmorning Menagerie, 2016) and The Night’s Belly (Toad Press, 2016). His creative and critical work has most recently appeared in Snail Trail Press, Kenyon Review, Quarterly West, Poem-a-Day, DIAGRAM, and others. He is the managing editor of Action Books, editor of Deluge, co-editor of Radioactive Cloud, and co-curator of the Yumfactory Reading Series. He is a PhD candidate at the University of Georgia. @p_cunning