Don Mee Choi’s new pamphlet from Ugly Duckling Presse, Translation is a Mode = Translation is an Anti-neocolonial Mode, explores translation as a radical regime utilizing the lenses of poetry, cinema, and American colonialism.

^

Don Mee Choi is a Korean-American poet and translator, primarily translating works of feminist Korean poetry, such as that of Kim Hyesoon.

^

The Korean Peninsula has been afflicted with many troubles caused by American interventionism since at least the start of the Cold War. “I come from a land of neocolonial fratricide.” Neocolonialism is a severing of autonomy. In the case of South Korea, it partially reveals itself through the dense spread of active US military bases across the country.

^

Mythologized warships perform drills in the surrounding waters. “It floats. It kills.” The Peninsula is disturbed by a totality of oppressive bodies (their symbols / their gestures).

^

Deleuze and Guattari say, “There is no mother tongue, only a power take over by a dominant language.” Choi expands upon this, saying, “So my tongue even before it had ever encountered the English language was a site of power takeover, war, wound, deformation, and, ultimately and already, motherless.”

^

Language is not an apolitical and ahistorical system. Its mutations are engendered by existing or emerging power structures.

^

The tongue is the vessel of language. It is the tool of utterance, but it is simultaneously the tool of consumption as well. And because these actions occur in the same space, they are inevitably capable of infecting one another.

^

Choi uses the example of oksusuppang. Oksusuppang, a food which was fed to South Korean school children after the Korean War, can be translated as cornbread in English. But these words do not equate to one another. They do not share the same distinct histories and contexts. These children did not eat cornbread, they ate oksusuppang. Even if the words, linguistically speaking, can be directly connected.

^

How does the translator navigate this system then? In which utterance and consumption infect one another, and in which seemingly correspondent words cannot embody one another?

Don Mee Choi says, “I traverse such order-words and map them, and superimpose another kind of map—the map of my dislocation…”

^

This dislocation, it seems, corresponds to a zone of deformation—the place in which these base terms mutate / where disconnects between language systems are further accentuated.

^

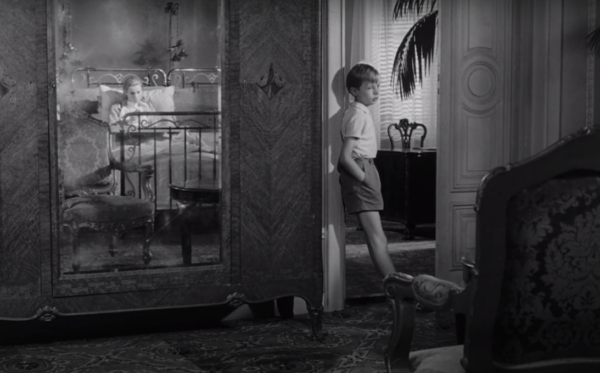

In the latter half of Translation is a Mode = Translation is an Anti-neocolonial Mode, Don Mee Choi analyzes scenes from Ingmar Bergman’s The Silence, which features predominant use of mirrors.

^

The Silence (1963) Directed by Ingmar Bergman

Choi formulates the mirror as one of these deformation zones. In which gestures are translated across the reflection of the surface. First from the primary body to the mirror to the eyes. Then from the primary body to the mirror to the film camera.

^

The deformation zone’s abstracted tactility spawns mystic qualities. Choi notes that the mirror is commonly used in Korean shamans’ rituals.

^

Mirror as translation surface

Mirror as armor

Mirror as chthonic navigator

Mirror as energy intensifier

^

“Inside this dark womb the possibility of all life is held.”

^

The mirror creates an ethereal space operating outside of the conventions of temporality. In Kim Hyesoon’s poetry, it is able to translate across generations and tongues.

^

The Silence (1963) Directed by Ingmar Bergman

In Bergman’s The Silence, it can be utilized for a kind of self-translation. Choi discusses in brief a scene in which one character looks at themselves in the mirror of a powder case. The powder case is empty, and thus the character is using instead to look at themselves—to translate.

^

The mirror infers a self-translation. The self-translation infers a separation between parts of the self. In the case of the powder mirror, it is a separation between the self and the facade. The facade displays a gesture (an utterance of the body) which the self is not inherently connected to.

^

The deformation zone of the powder case unifies the self and the facade. But because it is a deformation zone, it also formulates a potential for this gesture to be mutated or to be severed of its context.

^

The mirror is a set of armor, but its translation also creates the potential of mis/re interpretation. The self may read the gesture without its context. Or perhaps does the self formulate the context of the gesture, which then the facade is able to project?

^

The Silence (1963) Directed by Ingmar Bergman

Don Mee Choi’s prose is imbued with a poetic power.

In her summary of The Silence, she says, “Ester, an ill translator, coughs up blood. The boy is Johan… who is not a translator, and therefore not ill.”

There is a concise yet expansive beauty to lines like this.

^

Here, translation is imbued with the image of sickness or illness. There is a way in which the deformation zone potentially affects the body that occupies it. The translator operating within this zone is then subjected to the dissonance between language systems.

^

The mirror’s use in chthonic navigation arises again. Thinking of this deformation zone in a context similar to the underworld—as a space in which the past can be visited /spoken to / at times resurrected.

^

Choi’s discussion of Korea and Bergman reconvene in the image of a newspaper of gibberish language. She notes that this scene in the film is most relatable because it is how she saw English as a child—as this utterly unfamiliar scribbling. As an other.

^

Gibberish is the language of a perpetual foreign-ness. It is always outside of understanding, although it is at times at least identifiable. But this gibberish is not apolitical. In Choi’s example, it accentuates the predominance of colonist powers in Korea.

^

“Interpretation is a political art.”

Translation becomes a radical regime, converting materials across form.

^

In the span of only 26 pages, Don Mee Choi is able to adeptly convey the expansive potentials and nuanced politicality of the translator. All of this while simultaneously detailing the oppressive neocolonial powers looming over the Korean Peninsula, and calling her peers to fully utilize their position as translator.

^

“The empire’s belly is perpetually bloated by war.”

Mike Corrao is the author of two novels, MAN, OH MAN (Orson’s Publishing) and GUT TEXT (11:11 Press); one book of poetry, TWO NOVELS (Orson’s Publishing); two plays, SMUT-MAKER (Inside the Castle) and ANDROMEDUSA (Forthcoming – Plays Inverse); and two chapbooks, AVIAN FUNERAL MARCH (Self-Fuck) and SPELUNKER (Schism – Neuronics). Along with earning multiple Best of the Net nominations, Mike’s work has been featured in publications such as 3:AM, Collagist, Always Crashing, and The Portland Review. He lives in Minneapolis. @ShmikeShmorrao