“As bodily metaphor, the grotesque cave tends to look like (and in the most gross metaphorical sense be identified with) the cavernous anatomical female body.”

—Mary Russo, The Female Grotesque: Risk, Excess, and Modernity

“Orchids of flower meal, peonies of meat, Alexander’s ampules from the Lust Garden of Suffering”

—Aase Berg, “Ampules from the Lust Garden of Suffering” (translated by Johannes Göransson).

“History itself becomes a monster: defeaturing, self-destructive, always in danger of exposing the sutures that bind its disparate elements into a single unnatural body.”

—Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Monster Theory: Reading Culture

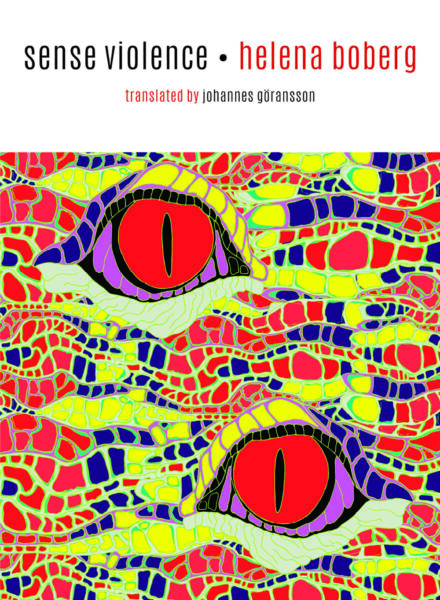

When I first read Helena Boberg’s Sense Violence, I thought a great deal about perceived monstrosity in the grotesque female body. Boberg writes, “Oh peonies / never has beauty / been so violent,” which is followed swiftly with “I wash myself in other bodies.” The constant associations of beauty and violence in this collection lend toward the horrific, the grotesque. The monstrous is always the abject, the thing which does not belong, but it is also a space of desire. Boberg’s poetry inhabits every monstrosity, showing the grotesqueness of the body and turning the mirror back to the gaze of the speaker(s) who labels it as such.

Sense Violence is gap-filled, the white space an illusion, a metaphor, a mockery. The language on the page has missing pieces. Some words are combined, removing the breath of space between them—“horrorstiff,” “bluecementhouses,” and “mouththroats”—while others stretch across the page, taking up as much space as possible:

“These

de-

composed

plant parts

that

like

in-

testiness

corrode

the air

Solve

soon

dis-

solved.”

The poems flood with syntactic precision, each slice of language placed just so. In an interview with Paul Cunningham, Boberg says that her collection could be read as an “accusation of consequences from gender normativity and masculine superiority that influences not only actions, politics, and justice, but also language.” Sense Violence physically shows the intensity of absence, the slits and fissures where pieces are missing. These poems explore how language moves among mouths: who controls language?

As the poetry shift perspectives, the pronouns and speakers altering in various sections, Boberg pays a great deal of attention to access in this collection, specifically who has access to controlling their own actions, who has access to other bodies, and who has access to language. The poems return to linguistic observation again and again to describe autonomy, specifically showing how language is male-dominated. Writing from the lyrical “I” perspective of a male voice (which I often perceive as a collective male voice), Boberg writes:

“As a word

she no longer

exists

outside me.”

The “she” becomes a symbol of the grotesque, an empty vessel that contains meaning only when in juxtaposition to the male speaker. Mary Russo writes, “The classical body is transcendent and monumental, closed, static, self-contained, symmetrical and sleek . . . The grotesque body is open, protruding, irregular, secreting, multiple, and changing.” Here, the female body fits the grotesque, lacking her own definition. Among other containers, the female body in these poems is a “bluebell,” “a clinic / with room for one,” and “Served / as an oyster.”

Each description verifies the gap of the female body, the open chasm. Again and again, the female body finds definition in relation to her lack of autonomy, a receptacle to be filled:

“The still warm smell

of a mass of people

remains

in her body

which is ours”

It is in this vessel, though, in this junction as an empty signifier that the female body in these poems enacts violence. The speaker uses this forced access, this unwanted assault, to envelop the aggressor. The self that is “barely / perceptible or / flower-like” embraces violence in return. In defiance of her own consumption, she begins to consume. Boberg returns to language as a measure of self-definition: the speaker says, “She versifies sanguinely / pushes her verbiage into my mouth.” The “she” remains abject; even her speech is bloody, the internal parts of her body exposed to the outside, but the language is her own.

The inhabitance of the poetry alters, the “I” slipping into another speech, another desire, another occupation: “I step inside the man.” These poems are slippery and surreal, engaging with so many different voices, playing card tricks with language. Boberg critiques bodily access and bodily excess, envelopment and consumption: “The only thing I’m thinking is that I want out of my own body.”

Hannah V Warren is a doctoral student at the University of Georgia where she studies poetry and speculative narratives. Her chapbook [re]construction of the necromancer won Sundress Publications’ 2019 chapbook contest, and her works have haunted or will soon appear in Passages North, Mid-American Review, Moon City Review, and Redivider.