What follows below is a continuation of AM Ringwalt’s Action Blog series – Citational Poetics. You can read her Introduction to the series [here] or Part I: “Cosmic Reordering” [here]. As always, thanks for reading the Action Blog!

“(We must never forget this question: what is literary criticism?)”

– Simone White, “Dear Angel of Death”

Simone White opens “Dear Angel of Death,” the concluding essay of her multi-genre book Dear Angel of Death, with an emphasis on the essay as an attempt. She writes: “We are cast about […] and must use a sense of qualities as belonging to ourselves and others to make an assay.” Since the essay itself begins after pages of a ‘playlist’—with titles of songs from dozens of musicians including Grace Jones, James Brown, Madonna and Minnie Riperton—White locates herself and her reader in a sonic space primarily consisting of Black music and thought. For the project of “Dear Angel of Death,” one examining “the question of how black innovation, literary and otherwise, is unprofitably tied up (hung up) on metaphors of musical improvisation,” a citational movement with musical and literary sources reveals the limits of the trope that the best Black art is always improvisational. White admonishes the “logic of blackness” as centering solely around improvisation—that is, White admonishes the critical reduction of Black art (and Black artists) to that of improvisation—because:

I’m concerned with the implications for contemporary black music, black writing and black life of becoming involved with a featureless invention or innovation as the main identifier of ‘African traditions of expressivity’; the implications for the space and time occupied by contemporary blackness by the call to innovate in the tradition.

Who makes this “call to innovate”? This “call to innovate” risks violence through a totalizing valuation of the Black artist’s restlessness—which seems to deny any singularity, any humanity and any need for rest. In “Dear Angel of Death,” White seeks to inhabit or at least map out a place of rest, while still exploring other modes of Black art and thought beyond improvisation, to answer the question: “How is it possible to get and stay between words?” To “get and stay between words,” for White, is an act resistant of the colonial violence of restlessness, an ongoing act performed by the essay itself through its emphasis on the spatiality of citation, one of a “bridge.”

White also implicates her reader through the opening of the essay—we are cast about, she writes, inviting her reader to apprehend the urgency of her project of reconfiguring. White notes that such an attempt can only happen through a twofold movement with the self and with others. As the essay progresses, White clarifies this intentional reconfiguring: “This is about how to learn. This is about […] taking part in radical desire to test new arrangements of the self.” White places her thinking in movement with others: W. E. B. Du Bois, Amiri Baraka, Fred Moten, Nathaniel Mackey, Vince Staples, Emily Dickinson. The essay—the assay—is structured in sections to contain and interlink each pair of thinkers and the thoughts that she constellates around them. Through foregrounding her writing as an attempt, and with the openness that the essay’s performative movement towards definition yields, White is able to flexibly move through several interrelated ideas. What begins with an exploration of citation as “linguistic intimacy” morphs into a movement with Deleuze’s folding (a movement that ultimately prioritizes Moten and Mackey’s folding); of gnosticism and betweenness; of nihilism, nothing. In this blog post, I will focus on White’s movement with linguistic intimacy in “Dear Angel of Death,” as all of the interrelated phenomena emerge from and are sustained by this motion.

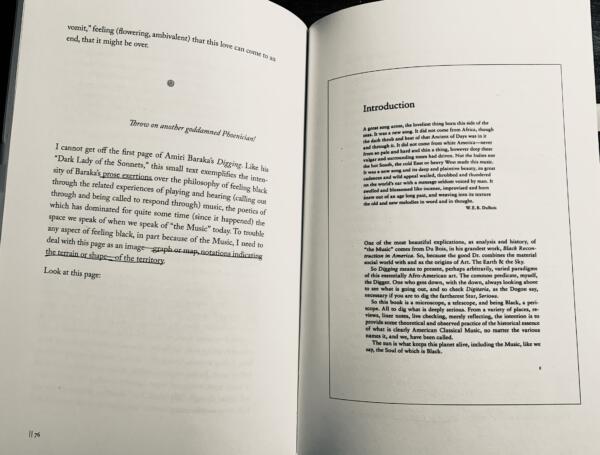

To get at this idea of citation as spatial, White provides a choreography for her reader. Mere pages after asserting “we are cast about,” White demands her reader’s participation. As White begins discussing the first page of Amiri Baraka’s Digging, she expresses a need to “deal with this page as an image—graph or map.” She needs her reader to deal with the page as an image, too. She demands: “Look at this page.” I perform her choreography by beholding the page. There, in the space of her essay, White includes the first page of Digging: half epigraph and half text, half Du Bois and half Baraka. This formal choice foregrounds the significance of citation, a process through which the “long quotation” functions as a “visual/verbal bridge” signifying an “order of linguistic intimacy.” After her inclusion of a long quotation, White outlines the readerly movement necessitated by citation—she performs the reader’s movement over this “bridge.”

First, she asks: “In order to look at the page, before we begin to read the words, professionally or unprofessionally, of, first, W. E. B. Du Bois, then Baraka, what actions must we take or must we take part in? I mean this both somatically and in terms of thinking.” White notes that Du Bois’ text, as epigraph, translates his very being (“all that he is”) into Baraka’s work. We apprehend the epigraph as an image first—an image of Du Bois—and then as a unit of Du Bois’ thought, and then as a symbol for Baraka’s inspiration and thinking. As “reader and text” draw close, as we “look at this page,” White clarifies the racial context of Baraka’s project of citation and moves towards the framework of her own project of citation. She notes that “the masculine order of black writing is an order that values being seen together: it is an order of claiming being together, not of hiding, not of disguise, not of suppression. The compositional assertion that the texts must be read together means something.” To cite is to defy the personal and social forms of hiding, disguise and suppression demanded by colonialism and by white supremacy. Instead of such an erasure, citation allows for a radical intimacy against colonialism and white supremacy, an intimacy where “these men [give] language to each other as its own kind of wanting to be together and wanting to be loved.”

From this articulation of intimacy, White presents her citational poetics. She notes that the “discourse of digging” dominant in Baraka’s work represents a possibility (or probability) of gendered violence. To “dig,” she reasons, is to “get with.” She writes: “Ask a woman what happens when a thing is acted upon in any of these gendered ways. (I want to get with her. I got with her. She could get it.)” Instead of digging, White seeks a consensual linguistic intimacy. When White cites, she does so with the other voice. Baraka’s “digging,” White notes, risks a physical and psychological moving into. She writes: “When I am ‘with’ the down, I am always free to get up and leave, to go back to the highly preferable up.” The freedom White writes of depends upon an environment of consent. To “always [be] free to get up and leave” comes from a trust in one’s safety; such a trust can only sustainably exist in a culture of mutual respect. When White performs citational poetics, it is with a freedom to affirm that “we are here together.” When White performs citational poetics, then, it is against Baraka’s “digging” and towards “the capacity of black people to move in a motivated way through time-space, toward the end of white supremacy, which is freedom, or also, the end of time.”

The particular freedom White consistently performs through citation in “Dear Angel of Death” is shadowed by the captivity of restlessness—and in her progression from R&B and jazz towards rap, White presents rap as functioning against “how freedom might be achieved,” signaling instead “what we are never going to have; […] what never comes.” She writes, first, on the restlessness of innovation:

I cannot hold the idea of innovation and the idea of tradition in my mind at the same time without thinking, but how does black writing take place if it is subject to the rigors of never resting? […] Is it possible to read a writing that never rests? How is it possible to get and stay between words?

And, in a fascinating and haunting movement with the near-Dickinsonian poetics of Vince Staples’ “Blue Suede,” in an articulation of how rap inhabits the impossibility of freedom (which she calls “the abyss, the organized space of blackness”) she writes:

A song like “Blue Suede” attempts to work in Dickinsonian ways; it cannot, although it SOUNDS like it does. Vince’s dexterity, his flow, his dark dark humor, the stuttering/scratchy grind that attempts to perforate the wail that swallows up loudness (producer=Marvin “Hagler” Thomas); these language and sonic acts work in the register of command. But achieving the “commanding certificate” (as Emerson says) is a cheap rap music trick that attempts to circumvent the grammars of race and structural poverty.

The Black artist-as-improviser exists in constant performance, flux, instability. This flux-as-violence, White suggests, yields the ever-active possibility of more violence—take Baraka’s Digging, for example. White writes, then: “JAZZ IS DEAD.” So, what space does rap inhabit? She says: “In rap music there is no inner space, no privacy, no singularity; there is, far in the future, the destruction of these conditions; there is the future.”

And where, then, does this leave Black writing?[i] White’s question of getting and staying between words—resting between words—heightens in urgency.

In White’s with-ness, I see a potential for new spatial movement, new forms of creating and new forms of rest. Through an articulation of citation as linguistic intimacy—where being with represents consensual relation—White provides a decolonial form of literary criticism, reading, writing and thinking. And that question was there all along, in her essay and catalyzing my writing by way of epigraph: “(We must never forget this question: what is literary criticism?)” White’s question of engaging with epigraphs specifically—and with citation more broadly—reaches towards social transformation, a transformation that charges a new kind of literary criticism: What actions must we take or must we take part in?[ii] The performative definition of the “drop” that takes place at the end of the essay—“‘TO DROP:’lose control over digital manipulation of; lose control over the musculature of one’s body/to fall down or faint/to lose consciousness; to render another person unconscious; […] to kill”—violently and vitally demands such active transformation.

__________________________________

[i] She writes: “The objective is that, for me, language that goes off doesn’t aspire to the condition of music; it aspires to itself.”

[ii] In an interview with Andy Fitch for the Los Angeles Review of Books, Fitch asks White: “Your fleeting reference to “black arts traditions” (lower case) points me towards this book’s wide-sweeping, transhistorical interest in ‘the question of the relation of black intellectual practice as art practice,’ but also towards the specific Black Arts Movement itself, with its uniquely (perhaps with Du Bois as precedent) generative fusion of poetic and critical and first-person practices. So how does Dear Angel’s hybrid project simultaneously point forward to what black arts or Black Arts still might become, what scholarship still might become?”

White replies: “Well I definitely do think of the Black Arts Movement as engaged with this question of: what is the relationship between black expression, action, and politics? I think of that as BAM’s fundamental question, coming out of Du Bois, and with ‘politics’ meaning a kind of totally self-transformational effort, and an engagement with the public, which doesn’t have to take some familiar form of political activism. So yes, to that extent, I do think of my intellectual work as weird political theory — as completely rooted in that particular procession, that particular history, and with multiple people taking it in different directions at present. You see a large effort by a lot of folks thinking: Well how does our work relate to larger questions of the survival of black people in the United States and worldwide?”

AM Ringwalt is a writer and musician. Her words appear or are forthcoming in Jacket2, Black Warrior Review, Peripheries and the Washington Square Review. Called “unsettling” by NPR and “haunted” by The Wire, her newest record “Waiting Song” will be released on October 2, 2020. @amringwalt