Five Poems by Sotero Rivera Avilés

Translated by Raquel Salas Rivera

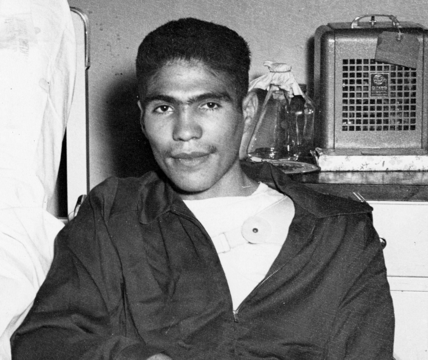

Sotero Rivera Avilés, 1953

On April 28, 1933, my grandfather, Sotero Rivera Avilés, was born in Añasco, Puerto Rico. Like most Puerto Rican towns, Añasco was built around the production of sugar cane. Rivera Avilés was the descendant of enslaved sugarcane workers. As a teenager, he worked after school in a bakery, making enough money to help care for his sisters. As he grew older, he realized very few options were available to poor black and brown men. Despite wanting to continue his studies, he soon learned that the University of Puerto Rico was reserved for the rich, which is why in 1951, without graduating from high school, he became a boxer. After a few years in the ring, he finally enlisted in the US Marines and was sent to Korea.

In 1953, at twenty-one, he was wounded during his service, losing an arm and suffering permanent damage to his left leg. During his post-war hospitalization, a family in San Francisco came across his name in the local paper on a list of hospitalized soldiers. They happened to share a last name. Basing their decision on this coincidental link, they took him into their home. With their support, he was able to complete a GED before beginning undergraduate studies at San Mateo College, where he eventually obtained an Associate degree in Arts.

After graduating, he decided to travel throughout Mexico as an independent journalist and writer. Records of this period are sparse, but the call of his barrio Humatas was strong enough to bring him back to Puerto Rico. Much of his poetry dealt with being a disabled veteran living in a small town while teaching at the nearby Mayagüez Campus of the University of Puerto Rico.

Rivera Aviles’ work is extraordinary in its scope. He most often writes within the more traditional lyrical style that was typical of the Guajana Generation. Yet he wrote about being a post-war veteran in a rural Puerto Rican town and the broken promises of Luis Muñoz Marín’s populist modernization projects. He demystified the jíbaro archetype of the naïve, but good-hearted field laborer saved by mass migration to urban centers, such as San Juan and New York. He wrote openly about his disabilities, delved into the seldom described experience of post-war return migration, and left a record of regionalisms from a world that no longer exists. His is some of the only poetry written about Humatas, and the breadth of his work never overshadowed the importance of the life he led before acquiring a formal education.

Although he is mostly associated with the Guajana Generation—named after the literary journal they coproduced—, outside of literary journals he shared few spaces with the group’s most well-known writers. There existed another Guajana, based in cities such as Mayagüez, far from the cosmopolitanism of San Juan. There, his interlocutors were writers such as Carmelo Rodríguez Torres, a Black novelist from the neighboring island of Vieques, and Luis Cartañá, a Cuban-born poet who taught in Mayagüez. Rivera Avilés organized readings and worked to keep the literary scene alive on the west side of the island. Alongside Rodríguez Torres and Jorge María Ruscalleda Bercedoniz, he founded the literary group Mester de poetas and the literary journal homónima (1967).

His early works include various poetry books: Nostalgia (1957), Abandonos (1958), Elegía mayor a la tierra: una estampa que debe leerse en tierra seca (1968), and the unpublished typewritten manuscript El Pueblo Obscuro y una puerta la jardín (unknown date), as well as a journal titled 1963. In 1974, Rivera Avilés won the Premio Ventana for Cuaderno de tierra y hombre. More than a decade later, it was followed by the publication of Nada pierdes, caballo viejo (Faena de remedios). In 1993, he finished his first and only novel, Con premeditación y alevosía: (Radiografía de un crimen).

On October 27, 1994, the man described by military officers as “a well-developed, thin Puerto Rican male who is alert and cooperative,” left us with the memory of a poet whose work was anything but complaisant. Instead of using the government check to pay for a traditional funeral, his wife and my grandmother, Virginia Castillo Beauchamp, decided to follow Rivera Avilés’ wishes. His body was cremated, and his ashes were scattered over the mountains overlooking Humatas.

Breve elegía al hermano caído

Te vi caer,

roto,

el cráneo despidiendo silbidos,

brazos y manos

como ramas desesperadas

y volviste agrietado a la tierra.

En mi recuerdo

habitas este duro pensamiento:

Sobre las rocas,

cabalgando el gatillo enemigo,

en la puerta del rifle,

y de momento,

roto,

partido en dos como una vara seca,

con ruido de astillas gritando.

Sabrá Dios

como la tierra te acogió;

qué ritmos tocará la lluvia

en la marimba hueca de tus huesos.

Yo, sin embargo,

sigo con mi tristeza de hombre alegre,

a veces exclamando:

Si tu recuerdo fuese una mano extendida.

Y otras veces

poniendo los pies en la tierra,

con deseos

de encontrarte otra vez,

Hermano mío.

Brief Elegy to a Fallen Brother

I saw you fall,

broken,

cranium sparking hisses,

arms and hands

desperate branches,

and cracked, you fell back to earth.

In my memory

you inhabit this hard thought:

On rocks,

riding the enemy trigger,

at riffle’s door,

and suddenly,

broken,

in two like a dry rod,

your kindling screeching,

God knows

how the soil received you;

what rhythms the rain beat

on the hollow marimba of your bones.

I, on the other hand,

keep up my happy man’s grief,

sometimes exclaiming:

If only your memory were an offered hand.

And other times

placing my feet on the ground,

wanting

to find you again,

my Brother.

Vestigios de pólvora

En la noche rabiosa,

después de aquel incendio y lamento,

quedamos muchos muertos y callados

en la agrietada luna de Korea.

(Charcos rojos mojaron el verano.)

Luego nos fuimos remendando

y otra vez

aprendimos a cantar canciones bajando otras montañas.

Mas,

si a cada día expiado

mi silencio es más hondo, más seguro,

aún escucho cierto ruido a fragmentos,

cual mensaje de hierro

con anotaciones de pólvora y tibio olor a sangre.

Así a veces me voy: taciturno en la noche;

débil en mi tarea de soldado ya viejo

que recuerda la guerra.

Gunpowder Vestiges

In the furious night,

after all that fire and lament,

many of us were left dead and stayed silent

in the cracked Korean moon.

(Red puddles soaked that summer.)

Later we started patching ourselves up

and learned once more

to sing songs descending other mountains.

But,

if with each atoned day

my silence is deeper, more secure,

I still hear something akin to fragments,

like an iron message

set down with gunpowder and a warm trace of blood.

Sometimes I wander like that: taciturn at night;

weak in my old soldier’s mission,

remembering war.

Epanáfora del vacío

Después de la gran borrachera nocturna

vago calladamente bajo los altos árboles.

Las viejas cogedoras de café me observan sentenciosas,

con un ritmo temblón y chismoso.

Piensan que soy un torpe vago,

que me baño desnudo en el río,

y recibo una pensión del gobierno.

Como el tedio me invita,

vuelvo por tardes a la tienda cercana

y me emborracho viciosamente.

Luego por las mañanas un poco frías

vago otra vez bajo los altos árboles,

sin nada que decir, ni pensar, ni esperar…

Anaphora of Emptiness

After the great nocturnal binge

I roam quietly under tall trees.

The old women who gather coffee observe sententiously

with a trembling and gossipy rhythm.

They think I’m a clumsy, lazy drunk,

that I bathe naked in the river,

and receive a government pension.

Since boredom’s paying,

each afternoon I return to the nearby store

and shamelessly drink.

Later, in the slightly cold mornings,

I roam again under tall trees,

with nothing to say, or think, or expect…

Domingo sin iglesia

Mi brazo artificial,

echado sin reparos sobre un mueble,

puede reír igual que un zapato sin rumbos,

destruido,

tirado a lluvia y noches

en el patio de entonces.

Comprendo su ironía

y he pensado

en viejos almanaques,

en toallas obscuras,

en vapores de incienso

cuando monjas

pasan bajo el calor de mi ventana.

…Y es que mi brazo artificial

………………comprende—

tiene ese don supremo de reírse

cuando piensa en el cura y las señoras viejas

que alzan su rabia y destrozan púlpitos

cuando ven pocos pecadores.

Churchless Sunday

My artificial arm,

carelessly tossed on some couch,

can laugh like an aimless shoe,

destroyed,

thrown to nights and rain

in what was once my yard.

I understand its irony

and have thought

of old almanacs,

of dark towels,

of whiffs of incense

when nuns

pass beneath my sweltry window.

…You see my artificial arm

…………………..understands—

it has that supreme ability to laugh

when it thinks of the priest and the old women

that raise their rage and destroy pulpits

if they see too few sinners.

Monday, July 22

203rd Day–16 days to come

Campo muerto, tiempo seco,

la herrumbre de la historia

Monday, July 22

203rd Day–16 days to come

Dead fields, dry season,

the rust of history

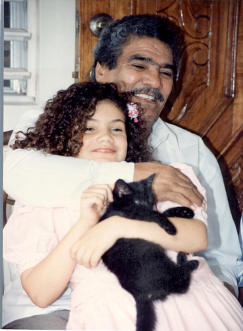

Sotero Rivera Avilés with translator Raquel Salas Rivera, early 1990s

Raquel Salas Rivera (Mayagüez, 1985) is a Puerto Rican poet, translator, and editor. His honors include being named the 2018-19 Poet Laureate of Philadelphia and receiving the New Voices Award from Puerto Rico’s Festival de la Palabra. He is the author of five full-length poetry books. His third book, lo terciario/ the tertiary won the Lambda Literary Award for Transgender Poetry and was longlisted for the 2018 National Book Award. His fourth book, while they sleep (under the bed is another country), was longlisted for the 2020 Pen America Open Book Award and was a finalist for CLMP’s 2020 Firecracker Award. His fifth book, x/ex/exis won the inaugural Ambroggio Prize. antes que isla es volcán/ before island is volcano, his sixth book, is an imaginative leap into Puerto Rico’s decolonial future and is forthcoming from Beacon Press in 2022. He holds a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature and Literary Theory at the University of Pennsylvania and now writes and teaches in Puerto Rico.