“… mankind cannot remain indifferent to its monsters.”

– Georges Bataille, “The Deviations of Nature”, 1930

1 – tortured, uneasy, ceaselessly watchful

With more arms than an octopus, sutured with legs and hands up to his neck: a

Meidosem. But not, for all that, radiant. Quite the contrary: tortured, uneasy, finding

nothing important to grasp, watchful, ceaselessly watchful, his head studded with suckers.(Henri Michaux, Meidosems)

Aspiring to symmetry, ideal proportions, unity, beauty, we are all misshapen monsters, warped assemblages of living cells, mental processes and ambiguous signifiers. We are bound up in ourselves, frustrated, lost. Our words don’t mean what we want them to mean and we don’t rule our bodies. Wretchedness is written into our DNA. More than any other poet or artist I can think of, Henri Michaux understood this. His odysseys into inner space brought him face to face with pitiful, tender monsters that express us more truthfully than any mirror.

2 – the eel of a handrail

Keen to effect the canonisation of Surrealism within the great Western tradition of Art and Literature, André Breton put repeated emphasis on beauty as the movement’s aesthetic aim. He argued that the juxtaposition or synthesis of incongruous images results in a convulsive beauty that disturbs and disrupts. He could have gone further and admitted that much of the most memorable surrealist poetry and artwork is monstrous; if it excites us, it is because it is inharmonious, threatening, wrong. We can wrangle over what beauty is, but the monstrous announces itself boldly, viscerally. Surrealism was a nest of monsters.

3 – Beauty and the Beast

Beauty and monstrosity are not wholly incompatible, of course; HR Giger’s xenomorph is one of the most beautiful organisms never to have lived.

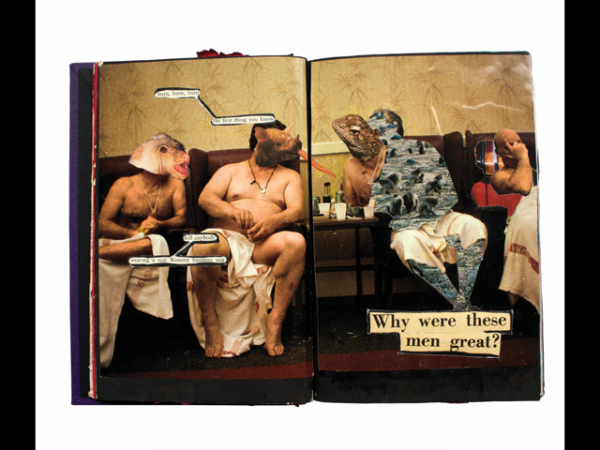

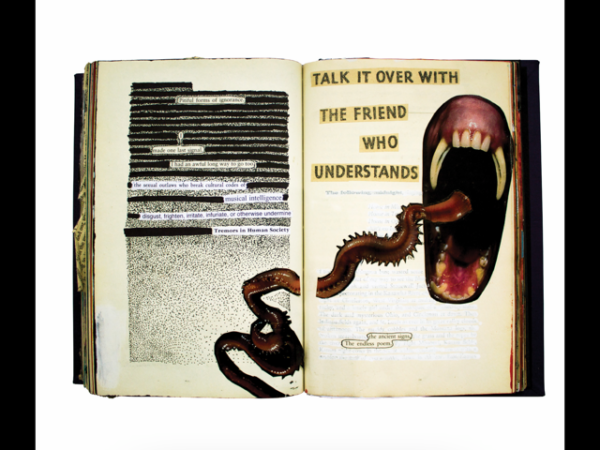

4 – the sexual outlaws who break cultural codes

Nightmarish hybridity has always been a salient characteristic of the monster, that unhappy creature made of things that don’t belong together. And how funny he looks, as well as terrifying! Cut-up and collage (processes by which things that don’t belong together are made one flesh) lend themselves to the monstrous, and to the black humour associated with it. Poet and artist ReVerse Butcher exemplifies this in some pages from her extraordinary artist’s book On the Rod (a feminist subversion of macho boy Jack Kerouac’s On the Road):

And as for cut-up monsters, look no further than the hilarious products of consumerism and celebrity culture fabricated (in part) from Men’s Health by Matthew Haigh in Death Magazine:

To play a monstrous vermin, De Niro didn’t just pull half his body out of

the living room but boxed with the boss. He also broke co-star Joe

Pesci’s numerous legs in one of the boxing scenes. De Niro’s jaws were

naturally strong.(“Robert De Niro”)

5 – re membering

Of all the arts, visual poetry is one of the most appealing. Much of the best visual poetry is elegant, intriguing, aesthetically pleasing, a playfully subversive processing of familiar signifiers. But there is a place for ugliness and monstrosity too; visual poetry should not limit its expressive range. Surrounded by the monsters of renascent fascism, environmental catastrophe, capitalist brutality and the Covid-19 pandemic, the visual poet can afford to get ugly.

6 – fearful symmetry

Symmetry is often considered the foundation of beauty, but the artwork of Alex Stevens reveals that the monstrous character of a disturbing image is multiplied exponentially by symmetrical figuration. Enjoy these examples: “Phantoms of the NeonCortex.”

7 – to find the core of body-flesh

The monstrous inhabits Johannes Göransson’s translations of Aase Berg, not just in its imagery and its interrogation of what it is to be human, but on a grammatical level: phrases and clauses are stunted or hideously deformed, words interpose themselves where they don’t belong, all is twisted, spiky, writhing. The poems read all wrong.

One morning I would hear you. The horn folded out and widened. I would

hear your waves break. I would feel the heart scream, hear the landscape

heave out of you. Where you come for to shine the Dovre meat through me.

Where you come shivering and hunched over your deformity.(“The Dark Dovre” in Dark Matter)

In Berg’s world the monstrous reveals itself in all life, animal and vegetable, sometimes combining those two categories, frequently encompassing raw mineral materials:

Where does this mass end? I search inward through strata to find the

core of my plasma wet from juices, to find the core of body-flesh

despite the outer, surrounding flesh, the naked body’s stable surface,

a kind of human here inside the bluing, plant-becoming.(“Life Form” in Dark Matter)

This imaginative synthesis of categories of matter embodies the surrealist adventure in a strikingly refreshing way.

8 – I stare at its tiny, grinding teeth

We are all too familiar with the comforting eeriness of the unheimlich, the deliciously fearful frisson we feel when a familiar object is subtly unfamiliar, or when home is not quite home. How much more powerful is the monstrous defamiliarisation effected by a hydra-like capitalism, insinuating itself into the very concept of home! In The House of the Tree of Sores, Paul Cunningham immerses the reader in a circle of hell constructed from IKEA flat packs:

The swelling mattress sides burst open, pushing milky leaves from their

coiling insides. Rusty springs and tangles of chicken wire. One mattress

pukes out a little girl covered in steaming leaves. Another mattress grunts

out a little boy covered in soil and wiggling maggots. My nervous system

aches.

The monsters of late capitalism father us, give birth to us, smother us. We may kid ourselves that’s not the case, but it’s healthier to face the basilisk, even as it destroys us.

9 – 666 likes

We try to mould ourselves, eliminate the outward signs of our monstrousness, our essential ugliness. We Botox lips and foreheads, look up at cameras, suck in cheeks, Facetune our selfies. We hide where the light is poor and filter out the ruin. But in all these attempts we make ourselves more absurd, more vulnerable. We attenuate to filaments and threads, snapping in a void, the reflections of Michaux’s Meidosems.

James Knight is an experimental poet and digital artist. His books include Void Voices (Hesterglock Press), Self Portrait by Night (Sampson Low), Chimera (Penteract Press) and Machine (Trickhouse Press). Website: thebirdking.com. Twitter: twitter.com/