“Is there any other way to be in this world?”

-Karla Kelsey and Poupeh Missaghi, “Matters of Feminist Practice: An Invitation”

In the introduction to this series, I described citational poetics as a deliberate and relational movement with other voices, one where the writer surpasses their self. Since then, I have been writing towards citational poetics as a form of being-with—a nonhierarchical form of attending to other voices, of mapping one’s own voice both in and because of the flux.

While I have explored several forms of citation in this project—through collage, text, photo and song—most recently I turned towards self-citation. Fanny Howe’s Night Philosophy, through echoing fragments from her other writings as a means of creating new and interlinked narratives, creates a sense of déjà vu for the reader. Time’s purported linearity refracts out and in.

As I was literally moved by Night Philosophy, I began to understand citational poetics as an active force. Whether one is citing their own work or the works of others, the reader is left with more to read, with more voices in circulation, with more questions and connections answered and unanswered. The reader becomes a participant in the text, tasked to follow the map of questions and connections beyond the form of the book itself. New forms of relation emerge past the page.

When I said that citational poetics are feminist and utopian, perhaps this is what I meant: the reader becomes active, expanding the map to include more and more voices. The work—not in the capitalist sense, but in the connection-making sense—is continuous.

*

At the beginning of this series, I turned to Alice Notley:

What would it be like to make a female poetry? […] What would another poetry possibly be like? […] Can there ever be any value in sexual polarization of activity? […] What is it like at the beginning of the world?

Why was it that most of the citational works I had read were by non-male writers? Why was it, that as I dove into this series, more citational works by non-male writers came to the forefront of my mind? My project multiplied. My project multiplies. I could have written about Divya Victor’s Kith, Lara Mimosa Montes’ Thresholes or Karla Kelsey and Poupeh Missaghi’s editorial work for Matters of Feminist Practice. And that proliferation is crucial: here are writers continuing this connection-making work, inviting new readerships into their citational projects, expanding connective space(s).

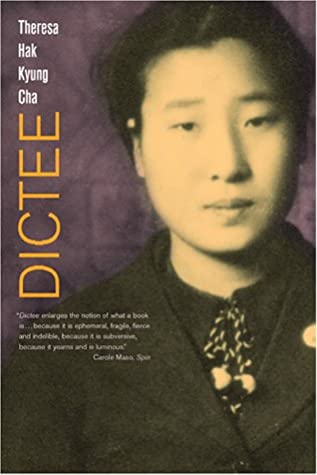

I have set this series aside for a few months, tending to necessity. But being able to re-enter this space speaks to the strength, fluidity and capaciousness of citational poetics. The work is continuous. Where I pause, others continue. In this continuation, I will think about Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee. Cha includes an allusive invocation in her text, a veiled citation.

She says it twice:

O Muse, tell me the story

Of all these things, O Goddess, daughter of Zeus

Beginning wherever you wish, tell even us.Tell me the story

Of all these things.

Beginning wherever you wish, tell even us.

*

Dictee may be the answer to Alice Notley’s question: “What is it like at the beginning of the world?” Cha’s answer, performed across a multipart, multilingual and hybrid form book, is unsettling. Despite the freedom suggested via the command “[Begin] wherever you wish,” Dictee opens with a performance of forced dictation: “Aller à la ligne” / “Open paragraph.” She “mimicks the speaking.” Through this process, this performance, we see Dictee’s “she” as a violated figure:

She allows others. In place of her. Admits others to make full. Make swarm. […] She allows herself caught in their threading, anonymously in their thick motion in the weight of their utterance. When the amplification stops there might be an echo. She might make the attempt then.

What is it like at the beginning of the world? “She” takes in speech, “She” takes in bodies, “She” takes in pain. After this, she inhabits the echo: “All the time now. All the time there is. Always. And all times. The pause. Uttering. Hers now. Hers bare. The utter.” She might make the attempt then—to begin. This she, open enough to contain the author, the author’s mother, Yu Guan Soon, Joan of Arc, Demeter and Persephone, speaks with a near-occult and opaque juxtaposition of oppression and subversion. Photographs, film stills and reproduced handwritten documents span the pages of Dictee, reminding the reader at each turn of the dynamic voices at play through Cha.

These voices feel less anonymous than the first she mid-dictation. They proliferate, at times ambivalently, cryptic in their movements. Still, there is a self behind each voice. Dictee is described as an “autobiography that transcends the self,” and with this “uttering,” “hers now,” comes a constellation of personal, cultural and political texts. In the flux, I perceive Cha: confidently arranging and rearranging, citing and ciphering. She begins wherever she wishes.

*

Cha’s mother, a recurring figure throughout the text, is shown stripped of her mother tongue, Korean. The figure of the mother parallels the opening of Dictee, wherein Cha stages a disembodied performance of dictation: She would take on their punctuation. A photograph of Cha’s mother, Hyung Soon Huo, is placed within the book. An epistolary text faces the photograph, as if Cha is speaking directly back to her mother. She writes:

Mother, you are a child still. At eighteen […] Still, you speak the tongue the mandatory language like the others. It is not your own. Even if it is not you know you must. You are Bi-lingual. You are Tri-lingual. The tongue that is forbidden is your own mother tongue. You speak in the dark. In the secret. The one that is yours. Your own.

As Cha writes of the violences of assimilation, she also performs speech from the forbidden tongue. What does it mean to own one’s tongue in secret? What does it mean to cite one’s secret tongue? The mother, the most emblematic of all female figures in Dictee—source of life while still bearing pain, still knowing pain—activates Cha’s citational poetics, grounds the project in a kind of tragic intimacy. On the final page of Dictee, she writes: “Lift me up mom.”

*

Cha achieved textual surrounding only to die in extreme violation, to be raped and murdered just days after the book was published. The dissonance between what Dictee represents and achieves, still, and what Cha was subjected to, haunts me.

She writes:

I am in the same crowd, the same coup, the same revolt, nothing has changed. I am inside the demonstration I am locked inside the crowd and carried in its movement. The voices ring shout one voice then many voices they are waves they echo I am moving in the direction the only one direction with the voices the only direction.

When I said that citational poetics are utopian, perhaps this is what I meant: there is always a possibility of violence. This is, perhaps, what the mother knows. Earlier in this series, I wrote: I wanted to be surrounded. Against violence. Is this like Cha’s plea? Lift me up mom. To continue to connect against such violence, to cite against such violence, gains power in proliferation.

AM Ringwalt is a writer and musician. Her debut book, The Wheel, is forthcoming in 2021 from Spuyten Duyvil. Called “unsettling” by NPR and “haunted” by The Wire, her newest record is Waiting Song. @amringwalt