I. Container

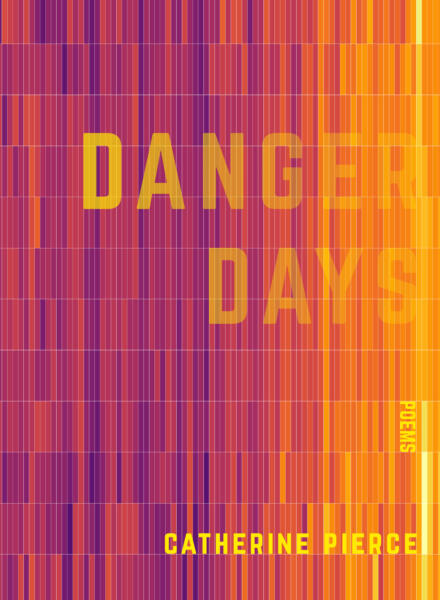

Catherine Pierce’s Danger Days is an overflowing vessel, containing so many worries and desires and disasters. The days are dangerous because of rising temperatures, rotten limbs, toxic algae, hybridity. The Anthropocene. Somehow, Pierce tucks us all within the world of her poetry, forcing us to reconcile her neatly lined poems with their critique of our effects on the planet: our inheritance and our legacy is destruction. And we cannot forget. “We remember, is what I’m saying,” Catherine Pierce writes. The hurricanes. The heatwaves. The television that “droned on about ozone / and acid rain.” Here, there’s no escape.

This collection provides a problem and hope for a solution: in the same poem—the final poem in the book—Pierce writes, “I’m ashamed / to say that most days I forget about this planet” and “I’m trying to see this place even as I’m walking through it.” In a way, this book works as a coy invitation, a call for readers walk through the world, “this place,” and imagine possible and impossible futures.

II: Horrorscape

Underlying this collection is horror, brief glimpses of skin-crawling. Pierce writes, “The soft brush / against your legs maybe fern, maybe fingers- / through-the-manhole-cover. Who could say.” These poems steep in something we can’t see, an unnamable fear flushed through the language that leaves us wary.

Pierce has a sly way of metastasizing ordinary experiences, connecting them to the strange, the unfamiliar. She invites terror into our homes. To speak of motherhood, Pierce speaks of space travel:

When the astronaut returned

to earth, more tests were run.

Scientists discovered that

seven percent of his genes

had changed in space.

He left the planet

as himself. He came back

as himself, rearranged.

Reading Pierce’s work, I remember the transformational bodies in both German fairy tales and contemporary horror films, the snap of a woman’s wrist as she turns into a laurel. Pierce tells us that a body changes. She tells us the world changes.

The apocalyptic poems, though, are unexpectedly tender. At the end of the end, after the inevitable burning of the earth, Pierce’s “Fable for the Final Days” suspects there will be “no weeping after a couple of weeks, / and then no people at all…as mothers turned / to bones and then to loam.”

III. Memorialized Future

Pierce’s knack for estrangement highlights the danger of it all. She marries the past with the future. In a poetic letter addressed “Dear children,” Pierce speaks from a collective voice, the we remembering what it was like to inhabit a child’s body: “[W]e understood that the future / was a country our parents would have / to navigate but had nothing to do with us.” Here, in the juxtaposition of memory and the imagined future, is the center of Danger Days. Urgency pulses through the poems, a call to look toward the inheritance we create for others—our left-behinds, our dim vision of the earth.

All the while, Pierce unremittingly returns to immediate physicality—the tactile present, rather than the past or future. She writes, “Do our crow’s feet show, and if so, / is it in the most self-assured way?” This collection vies with what it means to be alive and aging in a world falling to dust and what it means, in motherhood, to introduce a new generation to a place ravaged by destruction while remaining beautiful.

Pierce leaves us with a slip of advice, a warning: “Don’t be afraid. Or do, but / everything worth admiring can sting or somber.”

Hannah V Warren is a doctoral student at the University of Georgia where she studies poetry and speculative narratives. Her chapbook [re]construction of the necromancer won Sundress Publications’ 2019 chapbook contest, and her works have haunted or will soon appear in Passages North, Mid-American Review, Moon City Review, and Redivider.