“[…] the ghost tour, like the ghost hunt, is about the sadism of the living. We want the dead to suffer for our pleasure: to continue to perform their deaths in excruciating loops because we find the spectacle of this idea thrilling.”

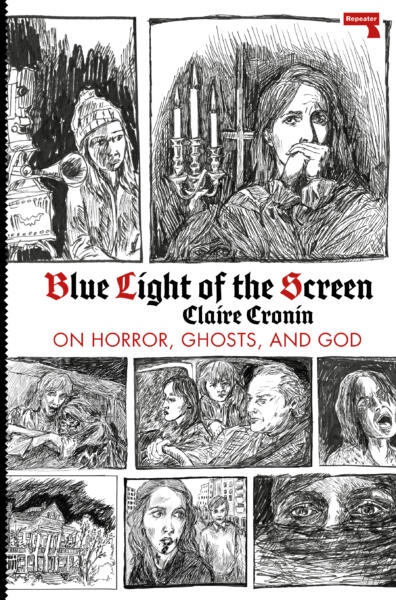

-Claire Cronin, Blue Light of the Screen: On Horror, Ghosts, and God

In May of 2018, I visited Pennsylvania’s Snyder Cemetery with my friend Q, a small cemetery where many children were buried during the 1800s. According to the gravestone outside its walls, none of the children buried in Snyder Cemetery lived past the age of 10. The cemetery is said to be haunted and a number of ghost stories exist (i.e. “Red Eyes”). Out of respect for the dead, Q and I remained behind the wall. I remember feeling very uneasy as I walked the perimeter. My body suddenly felt very warm. I didn’t feel like myself again until we returned to the car.

That same day, Q and I walked over a footbridge above a creek in a nearby park. He looked at me and asked, “You ever look over a bridge and worry you might see a dead body?” Later that evening, we came across a dead deer in the same creek. It looked like it had been shot in its stomach. Its entrails floated at the surface. Its body appeared stiff. Like it wasn’t real. We were both speechless. Who knows how long that deer had run before collapsing in the water. The next day, I was bitten by a tick. A few weeks later, after returning to Georgia, I collapsed in my bedroom. I could barely stand up or walk. I was eventually hospitalized for Lyme disease.

Many of us laugh at the thought of curses and hauntings, but I think about my visit to Snyder Cemetery often. It was as if my presence alone had agitated the landscape. And that’s coming from someone who has willingly spent a lot of time hanging out in the Allegheny Cemetery. But Snyder Cemetery felt different. An incredibly isolated tract of land, the grave markers inside the Snyder Cemetery have somehow still suffered years of despicable vandalism. I simply wanted to see it with my own eyes and maybe experience something. A supernatural happening? I really don’t know what I was anticipating. But I did not witness a happening and I did not see red eyes. I mostly felt a feeling that I can only describe as pain. The kind of lumbering, inexplicable pain that I think Claire’s book navigates in powerful, meaningful ways. Whether in the hands of the living (or the dead), Blue Light of the Screen feels like the perfect guide for exploring a variety of emotional and spiritual states.

-Paul Cunningham

Paul Cunningham: In your debut book, Blue Light of the Screen: On Horror, Ghosts, and God, you share a memory of a time when your mother had a group of nuns conduct a long-distance exorcism on you. They said you were not “possessed,” only “cursed,” but the curse had eventually been lifted. Early in your book you write, “I’ve always felt haunted.” Was there any point during that experience when you believed that you had, in fact, been cursed?

Claire Cronin: No, at that time, when I was sixteen, I didn’t think anyone had put a curse on me, and I was offended that that was my mom’s opinion. I was a depressed teenager, and my depression was a mystery to my mother, and she was very frightened by it. She went to the explanation that made the most sense to her, which was that I’d come in contact with a secret witch at my high school who put a curse on me.

But I do mean it when I say I’ve felt haunted by an unseen, impersonal force. I’ve felt that way throughout my life – not just when depressed, though depression can feel very supernatural. It is as if an evil power within me wants me dead, and its sinister desire colors all my thoughts. When I’ve been in the grip of that, I’ve prayed like a person who is damned. But it’s a feeling distinct from a curse, which I think is about bad luck and terrible things happening to you.

More broadly, maybe everyone is haunted. We’re born into history and mortal time. We carry our familial and collective pasts within us, and so the thoughts, feelings, and experiences of people who are dead can affect us on some eerie level. The human spirit is porous.

In the book, I wanted to write about states like this without being reductive. So, that meant going beyond secular ideas of human psychology and exploring the phenomena of hauntings, possessions, and curses as real possibilities – without, I hope, falling into total delusion.

PC: You suggest praying for the dead might “invite more pain.” I wonder about this myself. You also claim that the living might have forgotten how to care for the dead. (Lately, it feels like the living have forgotten how to care for the living.) What or who do you view as responsible for what feels like increasing examples of “horror tourism”?

CC: I don’t know that we can blame horror tourism on anyone or anything in particular. I’m not sure that it’s a uniquely American phenomenon, or even a uniquely twenty-first century one. There are accounts of very macabre, gothic forms of entertainment in earlier centuries and cultures.

While I criticize ghost tours and ghost hunters for how they exploit the dead and treat trauma as entertainment, I also think I’m culpable. I’m a horror fan and I like ghost stories. I take pleasure in images and narratives of suffering. Is that sadism? I don’t know. I’m trying to reckon with it.

Maybe today’s supernatural horror tourism says something about our relationship to belief. A person participating in a ghost tour must, to some extent, believe in the possibility of ghosts, or the tour wouldn’t be scary or exciting. But if they sincerely believed that the dead persist, I think they would find the tour distasteful. Ghost tours would then become solemn events – more like a requiem mass than a carnival ride. As it stands, the idea of belief itself is titillating.

I write about this in the book, so I’ll just quote myself: “We want the dead to suffer for our pleasure: to continue to perform their deaths in excruciating loops because we find the spectacle of this idea thrilling. Do we hate the dead because we fear them? Can we fear a ghost and not believe in its existence at the same time?”

PC: I was intrigued by your concern for child actors in horror films. It got me thinking about characters like Damien in The Omen (1976)—known for its purportedly haunted film set. Can you say more about why the idea of child actors unsettles you?

CC: Haha, well I haven’t really theorized this. There’s just something unnatural and uncanny about child acting. And as a viewer, I can almost never take child actors seriously – they pull me from the fiction of the film because their lines feel doubly rehearsed. Maybe it’s because children are already putting in so much effort to perform the roles of adults, so to play a character on top of that is even more absurd, or it reveals the performance that the child is already engaged in. Or perhaps child actors are disturbing to me because I was pushed to do a lot of performing when I was a kid. I started playing guitar when I was four and began writing songs in first grade, with intense encouragement from my dad. I was very eager to impress adults, but it left me with a weird feeling later.

Illustration by Claire Cronin

PC: “I keep reading about how blue light from screens tricks our brains into staying awake. Something about halting the production of melatonin—that sleep inducing ‘darkness hormone’ I’ve taken as a pill each night since I was twelve.” Aside from the title and your early mention of blue screens, the book often feels like a meditation on the color blue (i.e. a blue house, a pale blue body, the spilling of blue wax, a blue-lit door). Does it have something to do with the suffocating trappings of screens—photographs, mirrors, smartphones? Do you believe many of us are stuck in what Baudrillard calls the “black hole” of the screen?

CC: Blue is a spiritual, ethereal color and a color of despair, so I found it poignant that the light from electronic devices is blue. Many years ago, before we were all glued to our digital screens, I remember going on night walks and seeing people in their houses watching TV – their rooms filled up with blue. It was always a melancholy glimpse of strangers’ lives. Then as now, the experience of watching TV or staring into the depths of your laptop or phone is ethereal, immaterial – you leave your body and enter a nonphysical plane. It is like dreaming or fantasizing. It’s also depressing and lonely, or a balm against loneliness.

I don’t think the world of the screen is a black hole we can be trapped in forever. The real world still exists. But you can become lost there for a long time, and the reality of the screen can blur with the reality of the rest of life.

PC: “When people claim that horror is morally perverse or that the genre is symptomatic of a decadent, diseased culture, then we are once again entering religious territory.” Absolutely. We re-enter religious territory because horror—and its Decadence—is about the obscene ( the out-of-sight). Decadence, like horror—written in an “age of progress”—is always having to apologize for its excess, its stories of apocalypse. Can’t horror be progressive? What does horror expose?

CC: Sure, horror can be and has been progressive. I feel like the main discourse about horror films these days is about how progressive the movies are (or aren’t), which is boring to me. Art doesn’t merely “reflect” cultural values or instruct viewers in what to believe. The experience of watching something violent or horrifying is much more complicated than that. Each viewer has her own set of beliefs, values, and identifications, and they might shift throughout her viewing of a film. So each horror story exposes something different… But in general, horror movies are about fear, and in general, people are afraid of violence, evil, misfortune, disease, death, the afterlife (or lack thereof), and the return of trauma. So horror exposes all of these things, whether or not we want to judge the genre as progressive.

PC: “Awakening at 3 am most nights, poems were delivered to her from some dark, unseen author.” I’m fascinated by the connection your book makes with Catholic superstitions, the number “3” (“3 am is the inversion of 3 in the afternoon, which is said to be when Christ died on the cross”), the way the past lives on as “dark sonics,” and Sylvia Plath. Would you say it’s accurate to approach Plath as an occult poet? A mouthpiece for the dead?

CC: Yeah, I think Plath fits within an occult poetic tradition, but in a more buttoned-up, formalist way than figures like H.D. or Allen Ginsberg or Jack Spicer. I don’t get the sense that she was visited by angels and spirits, like H.D., Blake, and Rilke. It isn’t ecstatic writing. She was certainly interested in occultism and practiced divination, and there is something necromantic and possessed about her poetry. I don’t know what supernatural or magical experiences she actually had.

PC: Can you speak about your fascination with the occult and how it extends to your poetry?

CC: Deep in my heart, I want poetry to have the efficacy of magical, ritual language. I want the words in a poem to not merely refer to real things, but to conjure them. I want the visions in poems to be real, supernatural visions, which reveal the past and future. I want the dead who speak in poems to be real ghosts, transmitting messages through the page.

I’m not sure if this desire can ever be fulfilled, but I sympathize with other artists who have also felt this longing. Some of them, like me, have found more inspiration in spiritual rituals and texts than in literary theory or art history. In prayers and spells, a string of words can cause the world to bend.

As for the occult in general, it’s something I keep returning to, and the debates I have with myself about its dangers and ethics are not unlike the debates of Renaissance monks. I wish I could talk to one of those guys about it.

I think the occult has always appealed to artists because it positions the imagination as the ground of reality. And occult rituals – both high and low – can be very artful and creative, involving music, movement, color, language, and mental imagery. The logic of magic – where one symbol, tool, or ingredient stands for something else and also calls it into being – is the same as the logic of metaphor. The state of mind required to create art “out of nothing,” so to speak, is similar to the mindset required for magic or deep prayer.

On a personal level, occult and religious paradigms help me to think about realities beyond the human. Spirituality is an antidote for (or escape from?) the deep trouble I think we’re in as a species and the frustration I feel with our limitations and failures. Other people might turn to Artificial Intelligence, or nonhuman plant and animal life, to feel hope about the future, but I prefer to think about God, ghosts, demons, and angels.

Claire Cronin is a writer and musician based in California. Her nonfiction book, Blue Light of the Screen: On Horror, Ghosts, and God, was published in October 2020 by Repeater Books. Cronin is also the author of the poetry chapbooks A Spirit is a Mood Without a Body (Salt Hill) and Therese (H_NGM_N). As a musician, she has released albums on Orindal Records and Ba Da Bing and toured nationally. @churchofdespair