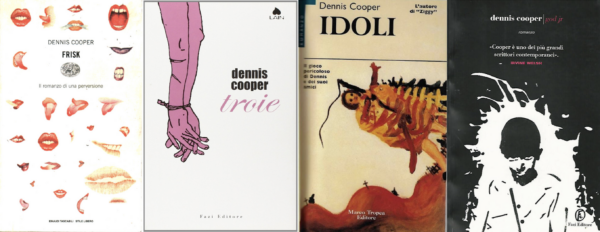

Frisk, Try (Troie), Idols (Idoli), and God Jr. in Italy

Paul Cunningham: As Diarmuid Hester points out in Wrong: A Critical Biography of Dennis Cooper, two of your earliest and most significant influences include Arthur Rimbaud and Marquis de Sade. You’ve called Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom a “giant discovery” at the age of 15. Aase Berg’s With Deer was my own giant discovery at 17. For a long time, Johannes Göransson and Joyelle McSweeney of Action Books have both argued that translation can have a renovative, transformative effect on U.S. poetry. Was it a coincidence that so many of the works that influenced you in the beginning were translations? If not, what do you think it was that was happening in those books-in-translation that maybe wasn’t happening in American poetry at the time?

Dennis Cooper: Rimbaud and Sade led me into French literature, and, really, into serious literature for the first time. And I immediately became a diehard Francophile. At the time, in my mid-late teens, the American poetry that was current and cutting edge that I knew about — the Beats, the mid-western guys, Bukowski, etc. — didn’t appeal to me. It was too freighted with autobiography and emotional crescendos and stuff, whereas the French poetry I read (Reverdy, Mallarmé, Char, the Surrealists, etc.) seemed more daring and colorful and untethered. I was doing a lot of psychedelics at the time, and the French poets were a good match. I didn’t get into American poetry until I found and fell in love with James Tate when I was about 19. His stuff led me to the 2nd generation New York School poets (Berrigan, Padgett, Notley, Mayer, Brainard, Elmslie, et. al.) whose work had the qualities I’d loved in French poetry but with this gorgeous US vernacular and lightness. After I discovered them, I was ‘all in’ on American poetry after that.

Frisk in France

PC: In The Paris Review, Ira Silverberg notes that your work was first translated into French in 1995. How did you react to this news at first? What was the first book (or books) translated into French? Do you recall any of those early reviews of your first books in translation?

DC: When my French publisher Editions POL started publishing me, it was a thrill beyond belief. The ultimate dream come true, really. They started with the George Miles Cycle novels. I think the first one they published was Frisk. And they’ve published all of my books ever since. Astounding luck. My French is terrible, and it was even worse back then, so I relied on my publisher giving me summations of the reviews. From what I gathered, they were excitingly positive and, more importantly, they seemed to really understand the novels in a way the American reviewers hadn’t. I didn’t have to deal with the ‘transgressive writer’ roadblock/tag over here because my work fits into a long-standing and respected tradition in French literature of dealing explicitly with ‘difficult’ subject matter.

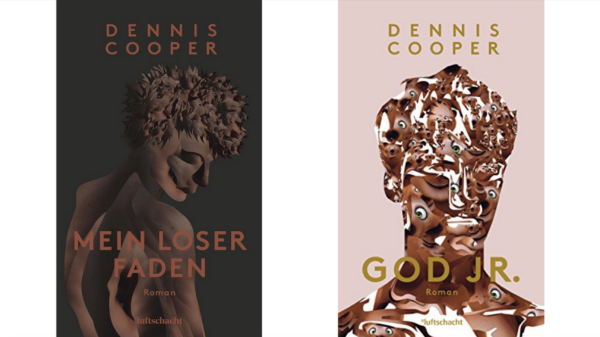

My Loose Thread (Mein loser faden) and God Jr. in Germany

PC: I remember God Jr. being published in Germany—2017, right? What was the reception of your work like there? What other languages has your work been translated into?

DC: I’m not sure what the reception of my work is like in Germany really. I keep getting published there, so I guess the response must be pretty good. Let me think … off the top of my head, the other languages my books have been translated into are Dutch, Swedish, Danish, Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, Greek, Polish, Hungarian, Hebrew, Chinese, Japanese.

Closer (クローザー), Frisk (フ リ ス ク), Wrong (その澄んだ狂気に), and Jerk (ジャーク) in Japan

PC: What works in translation have you read recently? Anything you’re looking forward to in 2021?

DC: Recently I’ve read the two Nathalie Leger novels that Dorothy published (The White Dress and Exposition), Ariana Harwicz’s novels Feebleminded and Die, My Love, Aase Berg’s Tsunami from Solaris, and I forget what else. Some small US press is publishing Pierre Clementi’s book Quelques Messages Personnels next year, and I’ve been dying to read that for decades, so that’s probably my biggest want.

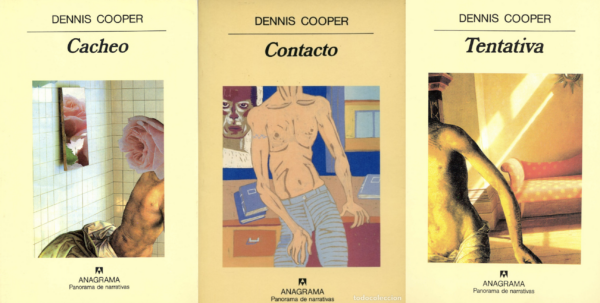

Frisk (Cacheo), Closer, (Contacto), and Try (Tentativa) in Spain

PC: Are there any untranslated French poetry collections or novels that you would like to see someone translate ASAP?

DC: Lots. People here in Paris are always telling me how much I would love a certain novel or poetry collection that hasn’t been translated. So many that I wouldn’t know where to start. I’ve long hoped that someone would translate Pierre Guyotat’s novel Prostitution. One chapter was published years ago in the US by Red Dust, and its translator, Bruce Benderson, told me it was absolute murder to even render that little piece of the novel into English because it’s basically impossible to translate. But that’s my translation-related pipe dream.

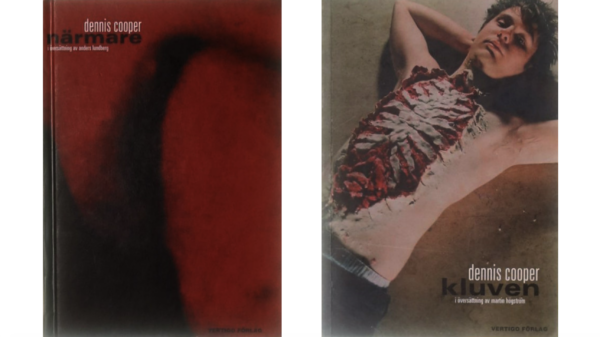

Closer (Närmare) and Frisk (Kluven) in Sweden

Dennis Cooper’s tenth novel, I Wished, will be published by Soho Press in September. With artist/filmmaker Zac Farley he has co-directed two feature films — Permanent Green Light (2018) and Like Cattle Towards Glow (2015). He has composed five internationally acclaimed first-of-their-kind fiction books composed entirely of animated gifs, most recently the gif novel Zac’s Drug Binge (Kiddiepunk Press, 2020). He lives in Paris and Los Angeles.

Paul Cunningham is the author of the The House of the Tree of Sores (Schism2 Press, 2020) and The Inmost (Carrion Bloom Books, 2020), and the translator of Helena Österlund’s Words (OOMPH! Press, 2019). He has also translated two chapbooks by Sara Tuss Efrik: Automanias Selected Poems (Goodmorning Menagerie, 2016) and The Night’s Belly (Toad Press, 2016). He is a managing editor of Action Books, co-editor of Radioactive Cloud, and co-curator of the Yumfactory Reading Series. He is a PhD candidate at the University of Georgia. @p_cunning