For me, Beauford Delaney is always connected with the sound of Elvin Jones’s ride cymbal. And if I were to think about describing that effect in terms of a particular word, not only at the level of meaning but also phonically, it would be “shimmer.” There is shimmer in Beauford Delaney’s painting in the way that there is shimmer in Elvin Jones’s playing. And for me that shimmer is totally bound up with what Samuel R. Delany calls “the motion of light in water.” When I hear that phrase, “motion of light in water,” it’s connected to a sound. And also, because it’s a motion, it becomes a question about movement. In a way, I feel like what I’m doing is a kind of reverse engineering, so to speak, of what immediately shows up as a synesthetic experience. You know, it requires a linking together of all these folks.

-Fred Moten in conversation with Jarrett Earnest, The Brooklyn Rail (Nov. 2017)

Originally, I wanted Elvin Jones’s shirt to have been painted by Beauford Delaney. I wanted to talk about Beauford as the greatest painter of yellow in the history of this world and any other. That whole Apollonian symbolic chain that associates yellow with sun, light, enlightenment, intelligence, revelation, brilliance seems so clear until you look long enough into the wreck of the collective head to see how and what yellow obscures and protects and enfolds and embellishes not unto the disappearance of the object but rather unto the continually Dionysian reappearance of a way. And so, with Elvin’s encouragement, and by way of the beautiful homophony that cymbal and symbol share, and practice, I realized we better try to approach Beauford’s yellow through his blue(s) which are not all blue. Imagine, then, this painting as if it were a singer—let’s call her Ethel, since in looking through the window of this painting, the sky is liquid with motion.

-Fred Moten, from “Blue(s) as Cymbal” (Nov. 2020)

Beauford Delaney. Blue-Light Abstraction, circa 1962. Oil on canvas, 25 3/4 x 21 1/2 inches

I recently attended Fred Moten’s lecture, “Blue(s) as Cymbal,” which reminded me of the 2017 interview above where he points out a sonic shimmer. A similar shimmer is at work in his 2014 book, The Feel Trio:

take your chance to make it up.

the sparkly blue is your engine.

the tree becomes your parapet.

the party that can make you fly.

you be the margin on the way.

Moten describes the blues in Delaney’s “Blue-Light Abstraction” as “not all blue” and as “liquid with motion.”

When it comes to Delaney’s work (an artist who is frequently associated with the color yellow), I remain mesmerized by the way neither yellow or blue feels dominant in the above painting. Knowing how Moten associates Delaney with the ride cymbal, I can, musically speaking, see how the presence of blue results in a more excessive yellow. And, vice versa, the presence of yellow causes a more excessive blue. Blue(s). The cymbals/symbols clash, perhaps resulting in, as Moten suggests, a “Dionysian reappearance of a way.” All or nothing.

Partially inspired by the Decadent queerness of the Yellow Nineties, I’ve spent several years amassing a collection of film stills for an ongoing color study centered around the presence of yellow in queer cinema.

Dorian Gray (1970) Directed by Massimo Dallamano

3 Women (1977) Directed by Robert Altman

I’m saving my thoughts on Dallamano and Altman for later. For now, I want to focus on the ways Moten’s thoughts on Delaney’s blues and yellows led me to revisit ideas of queer excess in a series of stills from Barry Jenkins’ 2016 film, Moonlight.

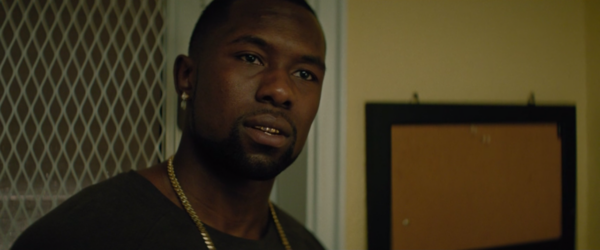

In the film, there is a scene where the younger version of the closeted character Chiron has a dream about Kevin—another closeted gay Black man—the morning before meeting him for a private moment on a moonlit beach. In the voyeuristic dream, Chiron watches Kevin have sex with a woman. Instead of exchanging eye contact with the woman, Kevin turns to face Chiron.

In Chiron’s dream, Kevin doesn’t mind Chiron watching him. He continues having sex with the woman.

For Chiron, this erotic fantasy—this excess of clashing blue(s) and yellow—is a way.

In Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, Lord Henry gifts Dorian a mysterious “yellow” book. From the description, it seems rather obvious (i.e. references to perfumes, ennui, etc.) that Wilde is alluding to Huysmans’ excessive French novel, A rebours. Dorian is comforted by this book. Like a drug, it becomes his own intoxicating and Decadent Bible:

It was a poisonous book. The heavy odour of incense seemed to cling about its pages and to trouble the brain. The mere cadence of the sentences, the subtle monotony of their music, so full as it was of complex refrains and movements elaborately repeated, produced in the mind of the lad, as he passed from chapter to chapter, a form of reverie, a malady of dreaming, that made him unconscious of the falling day and creeping shadows.

In Moonlight, the queer excess of Chiron’s sex dream feels appropriate because the future for Chiron (who is nicknamed “Black” during his youth) remains uncertain.

As long as Chiron remains in the closet, all he has is fantasy.

The Black characters in Jenkins’ Moonlight are often lit in soft blue and silver tones—an implied moonlight. During the scene on the beach, differing concentrations of yellow shimmer form around the heads of Kevin and Chiron. Kevin’s shimmer is more pronounced and halo-like. His yellow shimmer is reminiscent of the way Shelley Duvall’s face, the subject of Sissy Spacek’s desirous gaze, is sometimes juxtaposed with a yellow lamp in Robert Altman’s 3 Women.

“You cry,” asks Chiron. “Nah. It makes me want to. What you cry about?” replies Kevin. Kevin eventually drops the tough-guy act and the two men share a kiss. Kevin, after masturbating Chiron, wipes his hand off in the sand.

Kevin, in the moment, refuses to accept the reality of Chiron. No future with Chiron.

Chiron becomes a residue.

Additionally, it’s important to note that the audience is never shown the moon. Instead, we, the viewers, are positioned where the moon should be, catching the queer gazes of Kevin and Chiron. We are forced to look down on the two men as Jenkins casts a light on forbidden queer desire.

Jenkins uses moonlight in a painterly way. He uses moonlight—shimmer—to translate the same-sex desire of two queer Black individuals.

“You ain’t never done nothing like that before, huh?” Kevin drives Chiron home. The car ride is a silent one. Chiron exits the car and thanks Kevin for the ride. “See you around,” says Kevin. Despite the warm tones, there is a coldness to the scene.

Alone, Chiron turns his back to the audience and we follow him into a blurring shimmer of lights. At one point he appears to smile, but it quickly fades.

Haunted by the ways he wronged Chiron, we eventually meet the adult version of Kevin, surrounded by cage-like yellow walls that resemble the pattern on the younger Chiron’s yellow shirt. Meanwhile, American flags, protruding from boxes of artificial yellow flowers, appear to taunt him.

The idea of a cage is, again, referenced in the concluding scenes.

A few drawings—one of a setting sun—swell between the two men as they finally stand together, reunited, in a yellow kitchen. Kevin cooks for Chiron. After turning on the stove, Kevin asks, “Who is you man?”

“I’m me, man. I’m not trying to be nothing else,” says Chiron. The atmosphere grows tense. Kevin sadly admits to Chiron that he never ended up doing anything he actually wanted to do. “I only ended up doing things that folks thought I should be doing,” he says. “I was never really myself.”

The film concludes with Chiron recalling his much younger self staring into a blue moonlit ocean. The young Chiron, symbolically lost at sea, suddenly turns to face the audience. Jenkins, confronting the viewer, takes the private and makes it public. He confronts the audience, holding them accountable.

…a malady of dreaming, that made him unconscious of the falling day and creeping shadows.

A yellow/blue crash of cymbals.

Paul Cunningham (b. 1989) is the author of the The House of the Tree of Sores (Schism2 Press, 2020) and The Inmost (Carrion Bloom Books, 2020), and the translator of Helena Österlund’s Words (OOMPH! Press, 2019). He has also translated two chapbooks by Sara Tuss Efrik: Automanias Selected Poems (Goodmorning Menagerie, 2016) and The Night’s Belly (Toad Press, 2016). His creative and critical work has most recently appeared in Snail Trail Press, Apartment Poetry, Kenyon Review, Quarterly West, Poem-a-Day, DIAGRAM, and others. He is a managing editor of Action Books, co-editor of Radioactive Cloud, and co-curator of the Yumfactory Reading Series. He is a PhD candidate at the University of Georgia. @p_cunning