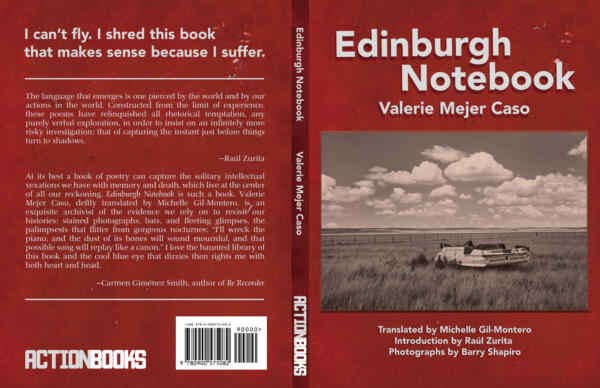

Valerie Mejer Caso’s Edinburgh Notebook (Available March 1, 2021!)

Katherine M. Hedeen: How did you encounter Mejer Caso’s poetry? This is the second book you’ve translated by her. Have your translations of her work evolved and changed? How? Why this book?

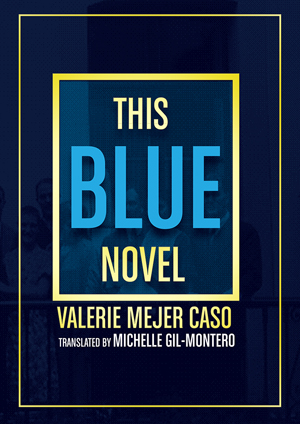

Michelle Gil-Montero: I read Mejer Caso’s poetry for the first time when C.D. Wright sent me Esta novela azul and asked if I would like to translate it for the Selected she was editing, Rain of the Future. I wish I could take more credit for that first encounter, but really, it was a generous, unexpected gift from a former professor whom I admired immensely. Joyelle McSweeney then published it as a separate book.

This Blue Novel is a book-length poem that flows like a novel, and I translated most of it in one rapt sitting. It caught me in its current—I never work that way! About a year later, I wanted to translate more of her work, so I began with the Movements section of Edinburgh Notebook. Those poems, as the ars poetica series in the book, were my door, and key, to the rest.

This time, so many echoes and cross-references guided my process; for that reason, I prefer to translate more than one book by a poet. The first time I read Edinburgh Notebook, I thought of a line from This Blue Novel: “I will introduce you to my dead, one by one.” I clung to that common thread: both books address the dead and greet loss as a defining presence in the poet’s life.

This Blue Novel alerted me to the importance of the apophatic approach in Mejer Caso’s work, especially in Edinburgh Notebook. The poem “The Creature,” for example, cobbles the speaker together with negations: “I’m not this,” “I won’t be that,” “I don’t have this.” The via negativa extends to time and memory as well: the present is merely a residue (“now is the echo”) of the past. Presences, and the present time, come to us already broken. In This Blue Novel: “the vase shatters and sings the song of the broken./ I squeeze a shard in my hand and bleed.” I can’t think of a better metaphor for the poetics of Edinburgh Notebook.

KMH: Could you speak to your influences in this translational process? Specifically, were there any poets, authors, translators that you were dialoguing with when you were translating? Who? Why?

MGM: Translation is a space riddled with rabbit holes. Every book has a different required reading list, playlist of songs, and gallery of images. I chased down many of Edinburgh Notebook’s epigraphs and references: Hemmingway’s “The Old Man and the Sea,” Pound’s poem “Portrait of a Lady,” a painting by Kobayashi Kiyochika, Camus, Duras, and others.

The Movement section of Edinburgh Notebook begins with the epigraph: “All shattered writing has the form of a key,” which is from The Book of Questions by Edmond Jabès, translated by Rosmarie Waldrop. That book influenced my translation in so many ways. I even used Waldrop’s word “shattered” (instead of broken) in several places throughout the translation because I wanted to echo this line.

I read The Book of Questions, which is a masterful translation, alongside Waldrop’s mediation on her process, Lavish Absence: Recalling and Rereading Edmund Jabès. Both books helped me to conceptualize Edinburgh Notebook as “shattered writing” and, through that lens, to recognize the ambivalence at the heart of the book. Like the Book of Questions, which is also a book of grief and exile/estrangement (Mejer Caso wrote this book while living in New York), Edinburgh Notebook desires, but fiercely resists, closure.

This ambivalence pervades the thought, torques the form. I caught on when I was reading Waldrop’s discussion of the ‘questions that answer questions’ in Jabès (“One of the disciples is driven to despair when he learns that every question only leads to more questions,” etc.; Waldrop 5). I spotted the same movement of thought in Edinburgh Notebook:

“Last thoughts?

The strange arrangement of clouds? The window, waiting?

Nothing, nothing, nothing? Or the faces of his girl and boy?”

And:

“Why does death wear fins like a diver? Why does its black, transverse scythe look like a flag?”

There is a nomadic, deflective movement of thought throughout Edinburgh Notebook. In my reading, the book rages against coherence and completion, because they are death; the poem always contains the “kernel of a severance” (Waldrop 7). “Shattered writing has the form of a key”—it unlocks closures, leads the way inward and onward.

This poetics resonates with me a lot as a translator—never a perfect answer, the text always necessarily incomplete, always deferring its finality, pointing elsewhere. Translation also responds to loss, and even grieves, in a way.

KMH: What are some of the main challenges you’ve encountered in translating this work? What creative possibilities did they open?

MGM: I felt anxious in my responsibility to the autobiographical dimension of the book. Accuracy is always stress-inducing, but the events that inform this book are real and traumatic. The first section, which contains language quoted from her brother’s suicide note as well as references to traumatic experiences in their childhood, felt particularly delicate. Her brother’s last words felt almost untouchable.

Early in my process, Mejer Caso talked to me a lot about the book. She is a phone person—I really like that! She told me about her brother Charlie, their father, and other people who appear in the book. She elaborated on passing references. She invited me behind the curtain, in a sense, and brought me closer to the book’s generating impulses. This knowledge gave me more confidence to edge beyond a superficial translation of the poems.

That said, Mejer Caso’s lines are incredibly inviting to translate—they make me itch to write. They feel malleable, maybe because they so quickly go beyond verbal play (which is Zurita’s observation). If I’m laced tight and aspiring to perfect literalism (as most translators do, on some level, at least at first), it isn’t long before I’ve abandoned that folly in favor of trying out sounds, leaps, little new feats of English. These poems, in all their own fluidities and freedoms, seem to ask for a translation that is willing to go beyond literal accuracy whenever the need for other kinds of accuracy (tonal, musical, etc.) arises.

I tend to work independently of the Spanish for at least a draft. Then, when I return to a line-by-line comparison with it, I sometimes leave minor omissions, additions, or restructurings. To do a translation that ultimately pleases me, I have to make room for my own intuition. Always, of course, I hew very close to the text and let it lead me. In one poem, Mejer Caso (who very rarely makes prescriptive suggestions) thought that I should add the word “Chilean” to a line. That addition clarified the historicity of the scene, yet frankly, I would have felt intrusive had Mejer Caso not invited it. I’m glad that Mejer Caso, a translator herself, is willing to “make originals” in this way (cf. Karen Emmerich). Why not? The book is fluid, never fixed, for Mejer Caso. Someone else has died, and now, we need to include those poems, too. In fact, several poems in this book did not appear in the edition published in Spanish.

KMH: Edinburgh Notebook includes collages made by the poet as well as photographs by Barry Shapiro. How did these other artforms inform your own work as the translator?

MGM: I’m glad you asked this question—it’s so important. I read the whole book as collage, in the way it confronts loss. It combines a reparative impulse to collect, and to re-collect, with the violence of that confrontation. There are so many sharp edges, violent positionings, recontextualizations. I was very happy that the collages were included—they are a map to the shatter, the “piecey-ness,” of the book.

The artwork informed my translation process directly, too—especially in the Postscript. They gave me another “original” —a proto-original—to reference. In some cases, they helped me to concretize details, to settle on the right modifiers. Translation and ekphrasis run so parallel, as it is. Translating ekphrastic poems is a double-response.

Fun fact, the book dialogues with a few pieces of art that are not included as well. The poem “In the Foreground” (which begins: “The four who face me, glaring. An astronaut, a shepherdess-poet, a village pianist, a woman in furs who rests her chin on the palm of her hand”) addresses the figures in a photograph (one of the four is García Lorca). Also, there is another collage of “The Creature,” which I like very much, that is addressed but not included.

KMH: What are you reading right now?

MGM: I recently finished Laurie Sheck’s lyric novel A Monster’s Notes, but I’m re-reading and taking notes for something I’m writing about monsters in translation. The Selected Works of Yi Sang, edited by Don Mee Choi and translated by Jack Jung, Sawako Nakayasu, Joyelle McSweeney, and Don Mee Choi—a marvelous, bursting-at-the-seams book. Yesterday I read Wild Peach by S*an D. Henry-Smith.

Michelle Gil-Montero is a poet and translator of Latin American poetry, hybrid-genre writing, and criticism. She has been awarded fellowships from the NEA and Howard Foundation, as well as a Fulbright US Scholar’s Grant to Argentina and a PEN/Heim Translation Prize. She is the author of Attached Houses (Brooklyn Arts Press) and Object Permanence (Ornithopter Press). She is Professor of English at Saint Vincent College, where she directs the Minor in Literary Translation. She publishes contemporary Latin American poetry in translation at Eulalia Books (eulaliabooks.com).

Katherine M. Hedeen is a translator, literary critic, and essayist. A specialist in Latin American poetry, she has translated some of the most respected voices from the region. Her publications include book-length collections by Juan Bañuelos, Juan Calzadilla, Juan Gelman, Fayad Jamís, Hugo Mujica, José Emilio Pacheco, Víctor Rodríguez Núñez, and Ida Vitale, among many others. Her work has been a finalist for both the Best Translated Book Award and the National Translation Award. She is a recipient of two NEA Translation grants in the US and a PEN Translates award in the UK. She is a Managing Editor for Action Books and the Poetry in Translation Editor at the Kenyon Review. She resides in Ohio, where she is Professor of Spanish at Kenyon College. More information at: www.katherinemhedeen.com

Poesía en acción is an Action Books blog feature for Latin American and Spanish poetry in translation and the translator micro-interview series. It was created by Katherine M. Hedeen and is currently curated and edited by Olivia Lott with web editing by Paul Cunningham.