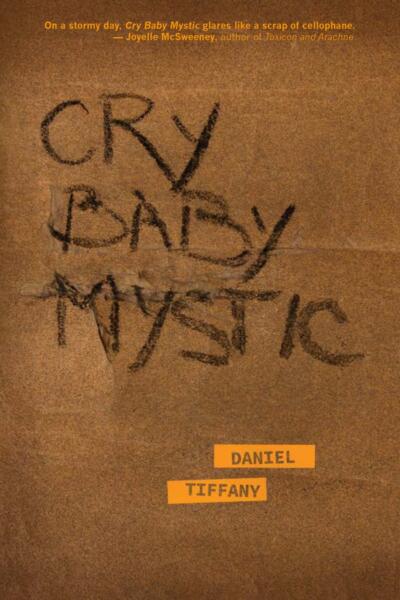

“Hyper-formal and bent out of shape,” is how Keith Tuma describes Daniel Tiffany’s latest book of poetry, Cry Baby Mystic. Divided into 10 sections ([EPILOGUE]; [CAPTION 1]; [STET]; [ALLEGORY 1]; [CAPTION 2]; [BRACKETS]; [EPILOGUE]; [ALLEGORY 2]; [TABLE]; and [STET]), this ambitious new collection from Parlor Press begins with an excerpt from The Book of Margery Kempe, in which we’re introduced to Jesus Christ’s “creature”—Margery Kempe—forced to cry pious tears at His command.

After reading several poems, I didn’t immediately understand why Tuma had described Tiffany’s collection as “hyper-formal,” and then it hit me: the syllabic patterns (i.e. two syllables in the first line of every stanza, four syllables in every second line, six syllables in nearly every third line, etc.):

“itself

be examined

mercilessly—who says

palaces ever were neat and

clean, what”(20)

“whose tracks

these are. Why art

Thou so far from helping

me and from these whispered words? Friends,

take me”(80)

Tiffany appears to be employing Adelaide Crapsey’s invention of the cinquain:

“I know

Not these my hands

And yet I think there was

A woman like me once had hands

Like these.”(“Amaze”)

Perhaps the cinquains were intended to give a formal shape to Kempe’s otherwise uncontrollable flood of tears. Cry Baby Mystic‘s cinquains might be hyper-formal, but the scope of Tiffany’s poems are startlingly capacious and, at times, reminiscent of the vast (yet miniature) worlds in the poems of Margaret Cavendish.

In a poem like “A World in an Eare-Ring,” Cavendish attempts to contain the known world in an otherwise ordinary object, similar to Tiffany’s Velázquezian mirror on page 45:

“Knowledge

of the entire

room sleeps in the mirror”

The kinesis and mimesis-driven “A World in an Eare-Ring” calls attention to both the materiality of the “eare-ring” and the vast immateriality of the sun’s orbit around the Milky Way, an orbit “we not see”:

“An Eare-ring round may well a Zodiacke bee,

Wherein a Sun goeth round, and we not see.

And Planets seven about the Sun may move,

And Hee stands still, as some wise men would prove.

And fixed Stars, like twinkling Diamonds, plac’d

About this Eare-ring, which a World is vast.

That same which doth the Eare-ring hold, the hole,

Is that, which we do call the Pole.”

Like Kempe, Cavendish, who appears in one early poem complaining about a non-functional doorbell in French (“La doorbell est fuckée”), strongly believed in the depths of one’s faith, but also likened God to the “immaterial,” something she separated from “natural reason.” Tiffany’s reference to something no longer heard—the unheimlich doorbell—again, reminds me of both Cavendish’s “A World in an Eare-Ring” and Margery Kempe’s daily tears:

“There Churches bee, and Priests to teach therein,

And Steeple too, yet heare the Bells not ring.

From thence may pious Teares to Heaven run,

And yet the Eare not know which way they’re gone.

There Markets bee, and things both bought, and sold,

Know not the price, nor how the Markets hold.”

In Cavendish’s poem, ornament (the “Eare-ring”) overwhelms both the eyes and the “Eare”. Like Tiffany’s non-functional doorbell, Cavendish’s church bells also do not ring. The speaker of Cry Baby Mystic refuses to “be sad in this world / just listen.”

Yet, to listen in these poems frequently means to contemplate the absence of sound:

“You could hear the kids put their friend’s name into the usual ring game, but without saying it aloud” (13)

“Either

of you boys want

a Coke?” I hear a smile

(26)The door-

bell is

fucked. I hate to

see the revelers go, she

says, the same one whose fingers combed

my hair(37)

you can’t be yelled

at by a tree—(56)

Tiffany asks us to listen with the “creature,” listen with the exile. And, given its curious section titles ([CAPTION 1], [BRACKETS]), Cry Baby Music asks us to listen with our eyes as a hilltop somewhere in the distance goes “mute / forgetting it spent the night as / a part / of speech.”

Paul Cunningham is the author of the The House of the Tree of Sores (Schism2 Press, 2020) and his latest chapbook is The Inmost (Carrion Bloom Books, 2020). He is the translator of Helena Österlund’s Words (OOMPH! Press, 2019) and two chapbooks by Sara Tuss Efrik: Automanias Selected Poems (Goodmorning Menagerie, 2016) and The Night’s Belly (Toad Press, 2016). He is a managing editor of Action Books, co-editor of Radioactive Cloud, and co-curator of the Yumfactory Reading Series. He is a PhD candidate at the University of Georgia. @p_cunning