Hannah V Warren: You’ve explicitly tied this collection to Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. Did you start this poetry project with Alice in mind or did she assume a larger part as you wrote? Even within the poems that don’t hold Alice so closely, I still see her influence. In “Three Months in Tennessee,” you write, “Seven months in this globed city, / and my husband tells me / this could never be home.” I suppose my question is, was Alice here all along?

Erin Elizabeth Smith: Some of the earlier poems in the book were written before the conceit of the collection became clear to me, but certainly edited with an eye towards that later on. Something that drew me to Alice initially, though, was the ways in which she moved through her world with a near lack of agency in the movement. She’s not traveling from place to place with a purpose, but moving forward because that’s what she has to do, a forward momentum of sorts that I found helpful in my own times of grief. The idea that we get through not because we’re trying to get somewhere else, but because that is simply how time works.

It was this realization about the book that led me to start exploring these ideas not just within the Alice story, but within the story behind the story of Charles Dodgson (AKA Lewis Carroll) and Alice Liddell. This of course opened up ideas beyond those of loss into ideas of historical inequities in who gets to tell stories and who gets to drive female narrators. In becoming Alice within the poems, I was also trying to reclaim my own story.

Alice Liddell as “The Beggar Maid” (1858) by Lewis Carroll. Albumen silver print from glass negative, 14 1/8 in. × 10 7/8 in. (35.8 × 27.6 cm)

HVW: One of my favorite movements in this collection is the shift from “The Deer,” a poem showing the contextual love of something—the irritation of deer stealing from a garden versus the “ecstasy and wonder” of seeing deer in the dark woods as a child—to “What We Undo,” a poem that so directly reflects that idea of circumstance. In terms of craft, what do you believe can be undone with poetry—can we use our language to undo? And, if so, what is the written practice of undoing?

EES: A professor once told me that the way we write is the way we remember. That the act of writing something cements the memory. In this way, writing can always be a way of undoing, of overwriting, of reclaiming. By writing the story with an eye towards hope, there becomes hope in a thing.

For me, there’s so much to the ways in which the creation of a collection, rather than an individual poem, allows for an undoing, or re-doing, of our own narratives, the ways in which we go back to our past and rework them into rising and falling action, an inevitability of character arc. I wonder, sometimes, if that is a reductive way of seeing our lives, but I think trying to find the stories, themes, narratives within our lived existence is also what draws many of us to writing in the first place.

HVW: I love the invocations of space in “Mapmaking” where I find markers of the Carolinas, Mississippi, New York, Tennessee, Illinois. “Here,” you write, “maybe I can / be another woman, free of topography.” How do you envision this liminality, this freedom from topography?

EES: When I moved to Tennessee, it was my 29th move in 28 years. I’d lived in nine states, and never been in one place for more than three years. So much of my existence was about the What’s Next of it all. To learn a place. To love a place. And inevitably to leave a place. To carry that place inside you as you moved on. Ironically, it’s in the fact that I’ve stayed still (I’ve lived in the same house now for a decade) that I’ve found myself even more tightly tied to place. While I’m not from Appalachia, having lived here for 12 years, I’ve found myself so deeply connected to this land, this history, the stories of season. I know when the redbuds will bloom and where to find oyster mushrooms after a heavy rain. I know when the sheep at our farm are ready to lamb and when to pull the last of the basil before the first frost. But in finding that sort of home, it’s also left me free of the liminality you mentioned, from the temporariness of everything that means. When I wrote these poems, I felt I had learned so much about so many places, but ultimately I wonder if I knew nothing but the veneer.

HVW: I would say that retellings seem to be in a boom of popularity right now, but I think they’ve always boomed. Can you speak to how you see yourself writing within this tradition of reframing/rewriting well-known narratives? What purpose do you believe intertextuality serves in contemporary poetry?

EES: Persona for me is a way for me to give new language and context to my own experience, to view through a funhouse mirror and see what new things I can learn. When writing “Alice to Alexandra,” for example, I was thinking about my own experience in my 20s of dating much older men. I had just found out that one of those people was now dating someone even younger than I was at the time. Realizing that you are a proclivity and not an exception to the rule is a hard space to be, and while I was not yet ready to write a poem dealing directly with that, I was able to instead focus on writing a poem about Carroll’s photography which focuses on putting young girls in provocative poses.

Alice Liddell (Summer, 1858) by Lewis Carroll. Wet collodion glass-plate negative, 6 in. x 5 in. (152 mm x 127 mm)

In looking to fiction as a way of looking to the self, we can see our own life as part of larger patterns—of hope, of love, of abuse. It shows us that we are not alone in the world and gives new ways for us to examine the context of our experiences.

HVW: In rewriting Alice’s narrative and placing her character in new, unexpected situations—on OkCupid, in a CVS parking lot, in Kentucky and Louisiana and Mississippi, in rooms with the red-shoed Dorothy or James Franco—how do you envision Carroll’s writing haunting your own?

EES: The further I got into the project, it was less the idea of Carroll’s Alice that haunted me as much as the girl behind the story, Alice Liddell. The idea that Alice does indeed grow up and fall in love and get married and make mistakes and exist for herself, those were the things that I wanted to see. While the child Alice is fascinating in her ability to adapt and inquire, I wanted to know the grown version who almost became a real-life princess. (Prince Leopold and her were thought to have had romantic inclinations towards one another.) To understand what it was like living under the shadow of this story that someone else told about you. (The haunting that that must have done to her!) To take the story back from the person who tried to name you something other than yourself.

HVW: Anyone who knows you also knows you’re a fan of culinary exploration, and this passion seeps through your manuscript, especially in descriptions of time and place. Even the seasons are defined by consumption: “November opens again, / to devour our sacrifice.” If you were to imagine your manuscript as a decadent set of recipes, what dishes would your audience find in the index?

EES: There would definitely be a peppery pork stew. Rabbit and dumplings. Crawfish. Directions on how to crack oysters and mix the perfect dirty martini.

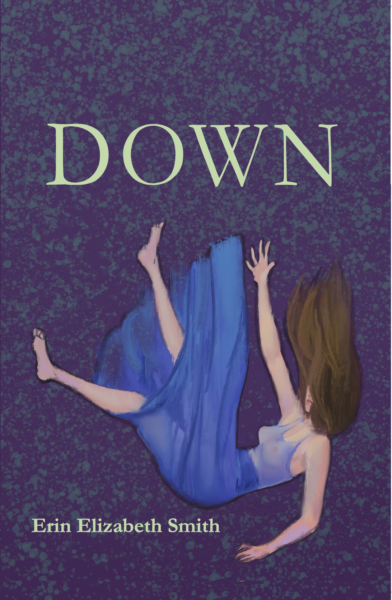

Erin Elizabeth Smith is the Creative Director at the Sundress Academy for the Arts and the Managing Editor of Sundress Publications. Her third full-length poetry collection, DOWN, was released in 2020 by Stephen F. Austin State University Press. Her poems have appeared in numerous journals, including Guernica, Ecotone, Mid-American, Tupelo Quarterly Crab Orchard Review, and Willow Springs, among others. She earned her PhD in Creative Writing from the Center for Writers at the University of Southern Mississippi and is now a Distinguished Lecturer in the English Department at the University of Tennessee.

Hannah V Warren is a doctoral student at the University of Georgia where she studies poetry and speculative narratives. Her writing and research interests focus on the grotesque, post/apocalypse literature, and representations of alterity. Hannah’s chapbook [re]construction of the necromancer won Sundress Publications’ 2019 chapbook contest, and her prose and poetry have haunted or will soon appear in Gulf Coast, Passages North, The Pinch, Strange Horizons, THRUSH, and Fairy Tale Review, among others.