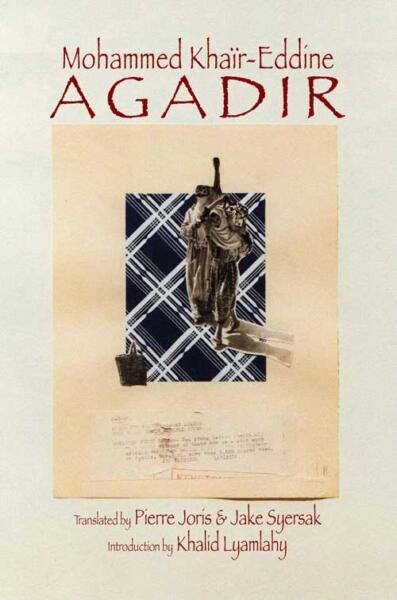

“I don’t have time for sleep.” In 1967, a devastatingly fierce 26-year old named Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine—fueled by the poetry of Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and Mallarmé—won Jean Cocteau’s “Prix des Enfants terribles” for his explosive, genre-defying book, Agadir (Lavender Ink/Dialogos, 2020). Thanks to the visionary intelligence of translators Pierre Joris and Jake Syersak, Khaïr-Eddine’s first full-length work of prose (or “hybrid novel-play”) can now be experienced by readers for the first time in English. Ferociously beautiful, Agadir follows a civil servant tasked with documenting the ghostly ruins of a destroyed city (“My city is not a vulgar jumble. It took me ten years to get to know it street by street, square by square”). Scarred by the events of the 1960 earthquake that resulted in 12,000 deaths, Khaïr-Eddine’s decadent speaker who “lives in the present,” endlessly wanders an Agadir that eventually feels more like an idea,

The city oozes, a red and white-veined yellow oil drops onto my memory’s soft folds. Roads in fits and starts toward the pale nakedness hoisted by the pylon’s night and the wind. The City toward the port, the railway station platforms, the swimming pools, the Kon-Tikis where my legs used to split the marine foam: My City that I carry along in my briefcase, My-City-Knife-Of-The-Sun. I don’t exhibit myself, I easily risk being understood. Here I reel in overheated tar on construction sites the tourists will discover at dawn. I mope and mope and scar by scar I feather my time, the time of a true tree frog.

or a piece of theater:

THE OLD MAN

It will never see the light of day, your city. Maybe it did exist, but I wouldn’t linger here anymore, I’m neither an archaeologist nor a kid. Look, I’m entrusting you with this piece of writing (he gives me a few handwritten pages); it appears to belong to a time when I was like you, but that time is fossilized, forgotten, buried under clods and embers of days and nights. I too thought I would make my way to a city. I didn’t get there. I FAILED.

While it’s no surprise that I remain perplexed by publishers of translations who willfully forego translator notes or Introductions, I must say how grateful I was for Khalid Lyamlahy’s highly informative contribution (“From the Wounds of the Past to the Library of the Future”). Newcomers to Khaïr-Eddine might very well wonder: Why has this so-called “major Francophone avant-garde poet” been so neglected in American conversations surrounding the avant-garde? Thanks to Lyamlahy’s Introduction, I learned many helpful details surrounding the censorship of Khaïr-Eddine, important biographical elements, his subversive aesthetic choices, and the historic influence of Moroccan rebellions. As more Americans make the choice to embrace new works of poetry-in-translation (i.e. Jorgenrique Adoum’s prepoems in postspanish; Yi Sang’s Selected Works), I cannot help but wonder: what long-term effect this will have on American critics’ conception of the avant-garde?

Paul Cunningham is the author of the The House of the Tree of Sores (Schism2 Press, 2020) and his latest chapbook is The Inmost (Carrion Bloom Books, 2020). He is the translator of Helena Österlund’s Words (OOMPH! Press, 2019) and two chapbooks by Sara Tuss Efrik: Automanias Selected Poems (Goodmorning Menagerie, 2016) and The Night’s Belly (Toad Press, 2016). He is a managing editor of Action Books, co-editor of Radioactive Cloud, and co-curator of the Yumfactory Reading Series. He is a PhD candidate at the University of Georgia. @p_cunning