Mike Corrao’s SMUT-MAKER is an important visual deployment in the realm of “closet drama”, updating it for contemporary reconsiderations of language as material (Derridean) space, emblematic of a current strain of thinking in visual and experimental writing centered around presses like Inside the Castle—that of literature and the book as a kind of ritual architecture, spaces wherein the text enacts itself.

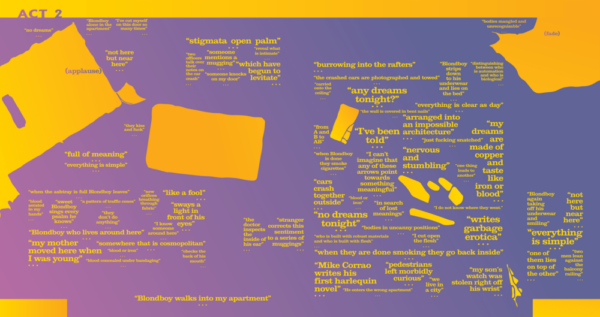

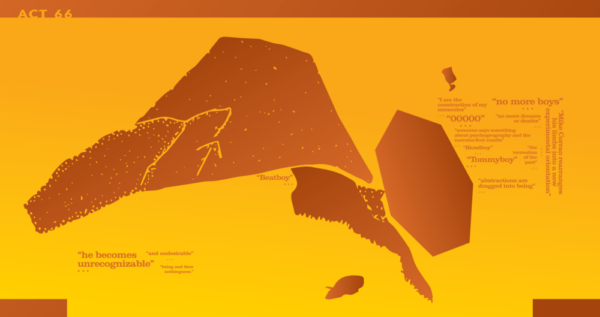

On the pages of SMUT-MAKER, we can begin to see how this thinking takes place; each double page spread besets the reader with a new kaleidoscopic color palette, splattered with blobs of color and nonlinear texts contorting themselves into various arrangements. The closet drama is a version of the verse medium intended to be read on the page rather than performed outside of it. But SMUT-MAKER extends this principle further—this 72-act play is not just intended to be read on the page, but rather the page itself is performing the play. The colored blobs often resemble ruins, rooms, and city streets, and text fragments navigate them as if they were actors moving throughout a set. The textual nonlinearity resembles the nonlinear choice of “reading” an audience has in a play: perhaps one viewer watches someone speaking; another watches a character’s reaction; yet another might keep her eye on the extras in the background milling about. In the same way, the viewers eye is encouraged to flow across the page-stages of SMUT-MAKER. And just like in a play, things may be lost to a reader—words eaten by the gutter of the book, or fragmented by the ebook’s dislocating of the two-page spreads. Only multiple viewings will allow the viewer to begin to understand the ‘structure’ of the play in its entirety. In this way SMUT-MAKER takes the premise of the closet drama and asks, “what does it actually mean for a drama to be intended for the page?” In that sense it is the closet drama for a current tendency in visual writing: if writing is physical, a codex-bound architecture, then why not perform a play within that architecture?

As a genre, the closet genre has been associated with writing outside the bounds of heteropatriarchal systems; in the early modern period, by restricting one’s readership of a closet drama to a specific readership, literate women were able to publish their writing as closet dramas, which often contained potential counter-imaginaries to dominant power structures. Take, for example Margaret Cavendish’s “The Convent of Pleasure”, wherein the characters create a cloister of unmarried women, creating (albeit however briefly and within the caveats of the historical resolution-logics guiding it) a space outside of masculine systems featuring homosexual desire and transfeminine crossdressing. Here, too, “SMUT-MAKER” evokes this tradition; depicting the three (ultimately dissatisfactory) sites of gay desire and sexuality in the form of the play’s various “boys”: “blondeboy”, “tommyboy”, and “beatboy”. These sites of homoerotic dissatisfaction each create, in their own way, various “closets” within the relational tensions each relationship inhabits and their particular social milieus. The emotionless, vomit-laden disregard, belief that one comes from the starts, the violence of drumming, a communicating that someone no interest in having sex with you are laden with reflationary tension, a suffocating anti-anti-eroticism which makes the city which that surrounds the characters of SMUT-MAKER feel like room unintended for human presence. Indeed, the city takes on this erotic tension, invoking the sexuality in car crashes, eyesight degradation, rocket explosions, and glossolalias of machine-generated text.

This is what I think SMUT-MAKER and the aesthetic tendencies it has found itself involved in operate out of: the ways in which books can make space expand and contract, both in the imagination and on the page. To create texts which allow the expression of particular subjectivities (or perhaps “object”ivities) not only through the voice, but through formal reworkings of what “writing” can be. To let you sit alone, in your own dark little closet, beneath the reading lamp, and find another closet, another personal architecture, rolled up between the pages.

INTERVIEW

Ava Hofmann: On the most basic level, the first things a reader encounters about SMUT-MAKER are its use of color, shape, and nonlinear text arrangements. What was the process of generating the page layouts and the book design? What was the process of ‘arranging’ the text? When reading, I was struck by the way the abstract shapes reflected the repeated symbols of the text in these sorts of hybrid ways – a page layout might look like the layout of a city, or a labyrinth, or a penis, or a splatter of vomit, perhaps all at once. And so further, within this process of generating these spatial texts, what was your thought process about how they related to thematic landscape of your play?

Mike Corrao: Originally, I had written SMUT-MAKER as a series of quotes separated by ellipses. It was pretty straightforwardly arranged in block paragraphs with these occasional parentheticals interspersed throughout the speech fragments. Things like the (applause) or (laughter) you see in the final. It was very much inspired by some of the formatting from Roberto Bolaño’s Antwerp. After Inside the Castle picked it up, we started talking about alternative ways to present the book. Thinking of the page as the stage on which the text performs itself. Trying to visualize this non-human theater, which occurs outside of the conventional temporality and performativity of the medium. We sized the book so that each spread could fit the entirety of an act (which had originally ranged from one to four pages). We also made the pages square, wanting that full spread / act to resemble the dimensions of a stage. For the set-dressing itself, all credit goes to John Trefry. He made these beautiful abstract structures and found these really compelling ways to have them interact with the base text. At the beginning of the design process, we talked about finding this mixture of theatrical architecture and organic materials. John sent me these pictures of Greek archaeological folios that he was taking inspiration from. Which adds a really compelling kind of dilapidation in my opinion. Since we are working off the remains of these structures rather than their speculated originals. I view these set dressings as equally important and participatory in the play as the text itself. They are the mise-en-scéne. Without them, there is no environment for the actors to occupy / inhabit. The technicolor landscape gives these signifiers an additional set of symbols to attach themselves to.

AH: Near the start of SMUT-MAKER, the text begins to make an important distinction between “what is erotic from what is smut”, a theme which the text revisits continuously in several forms: from the described sexual encounters between the Narrator-Fool, and the three “boys”, to stranger and subtler elements like the description of doors as yonic, and collagist juxtapositions of sex with car crashes and rocket launches. These sorts of forays into “smut” as opposed to the “erotic” makes me think also about the history of the suppression of homosexual art under charges of “obscenity”. What was your thought process with the ways in which this text navigates the sexual and sexuality?

MC: SMUT-MAKER is deeply personal for me. It started as this kind of self-interrogation, trying to figure out how I feel and what I want. Which is the origin of the Narrator-Fool. There’s something very funny to me about placing yourself in a book, and then pointing at that character and mocking / laughing at them. That character’s failed sexual encounters I think are an expression of my anxiety around my own sexuality. A lot of the time that anxiety is expressed through this farcical failure, but other times it combines with my anxiety towards the body. Sex becomes this metamorphic trigger. It can turn a wall into flesh or penetration into a car crash. It almost feels viral. Like something that can crawl into you and fuck up your body’s inner processes. The failed encounter can be a defense against that potential metamorphosis and intimacy.

AH: Another consistent and perhaps related theme is that of the body as a site for failure—everyone’s always vomiting in this book! But more than that, there’s this ongoing narrative with the Narrator-Fool’s eyesight worsening in increasingly surreal and abstract ways, and things like Beatboy playing the drums so hard that his hands begin to bleed. Bodies may mutate and shift form or become mangled in various ways. How does your practice work through the body as a site of both failure and as a site of mutability?

MC: I have a fear that when I am not looking that my body will rot and fall apart. I have always felt ambivalent about having a body. It feels strange and foreign yet completely and irremovably part of who I am. It is me and not me. This is most accentuated in certain places of dissatisfaction—like body fat or blemishes or injuries. When I hold my stomach fat in my hands, something feels off. It feels like a mutation or an anomaly in my anatomy. As if it is not a real part of me but a cyst to be cut off. Same with blackheads or a crooked tooth. There is this sense that the body has a root form which then undergoes these mutations to become less itself. But I do not know what that root looks like. I don’t think it’s real. I think it’s the result of an unhealthy understanding of what having a body is like. But in this idea of the root, I am drawn towards the idea of stranger and stranger mutations. What if the root is not altered by blemishes but by newly sprouting limbs or slimy secretions. Contorted ribcages. The body is a site of unknowability. It is the fragile little container that we are all piloting.

AH: SMUT-MAKER has an extremely interesting, direct approach to the theoretical-philosophical and artistic thinking which has defined its approach in a kind ‘cloud of allusions’, from Sun Ra to Derrida to Bolaño to (not) Proust. Indeed, the text almost has this lackadaisical approach to these texts, an ambivalent or half-hearted set of formulae which gesture at theorizing itself. The text might make jokes about difference/différance, or deploy its repeated frame-formula “in the tradition of [blank]”, cycling through a wide array of contradictory thinkers and artists. There’s even this hilarious sequence wherein the text introduces this idea of the “schizopastoral” which is then quickly and continually “criticized for its underdevelopment” and “reconsidered”. How did you go about involving a wide variety of theoretical and artistic traditions as a part of your practice in these direct, allusive ways?

MC: Thank you! I’ve come to kind of love the schizopastoral—the landscape of mouths. I don’t entirely know where it came from haha. The name is a play on Joyelle McSweeney’s necropastoral, but beyond that… I don’t know… I’m interested in the disembodied voice, and especially in this theatrical setting, how disembodied voices interact with one another. Often it feels like they are not in conversation but that their function is instead more textural. They are materials used in the construction of a building. Components in the collage. The appearance of theoretical-philosophical figures act as a kind of shorthand. It forms a portal between this work and the figures / concepts mentioned. Much of the writing process for me is (to use Monica Belevan’s term here) semiautomatic. It isn’t necessarily guided by the unconscious, but by some other hand—what I’ve been reading and watching and playing. With what I’ve been interacting with. I like to take in a lot of media while I’m working, whether that be watching YouTube videos or playing music. I’m very much drawn towards this idea of the mass of data. Of creating a work that is not narratively cohesive necessarily, but rather gathers all information that could surround a narrative. Kind of like a TTRPG book creating the world and its rules rather than the strict stories that occur within it. I am much more interested in potentials than actualization. T use of those theoretical-philosophical figures is most often a means of expanding the reach of the text, and bringing these complex, outside readings into the mix.

AH: I also want to expand on this idea of ‘formula’ or ‘algorithm’, because several moments in the text seem to operate as if they were the shifting around of variables or numbers. There are obvious things, like the repeated invocation of “0000” and several pages at the end which employ long streams of random characters that evoke URLs, but there other, more language-driven ways in which these kinds of formulae appear—the pages which employed “an X which looks like X” comes to mind, as well as a page which seemed to iterate through random variations of “I” “you” “uh” “no” “know” “mean” and “yeah”. What is the role of these automatisms in this play, and in your process as a whole?

MC: I’ve slowly been incorporating more and more automated processes into my work. A few years ago I started teaching myself how to use a program called, Twine, which is often used for choose-your-own-adventure games. But I learned that there’s a lot of interesting it can do with probability and with boolean functions. So I started making these smaller programs to determine segments of a text. With SMUT-MAKER I wanted to expand the schizopastoral beyond traditional speech. I wanted to work in this kind of glitchiness to an extent, like not all speech was real. Some of it was an error or nonsense or formulated rather than felt. Without the automations, the schizopastoral felt more like eavesdropping than occupying a landscape of utterance. But with this added repetition that idea of language as a material comes back. Seeing a base-phrases with new variables is like seeing the same trim around the base of one room as in another. It’s a haptic kind of motif. Not necessarily a recurring idea, but a recurring mechanism. Which I find really compelling. I feel that a lot of writing is not concerned with the mechanical act of writing or the mechanical construction of language as this system of symbols. With these weird little automations, I wanted to play at the structural qualities of words / glyphs.

AH: What is the role of architecture, cities, and labyrinths in your work? My impression of SMUT-MAKER consists of a series of revisited and personal rooms—laundromat, coffee shop, bedroom—juxtaposed with the larger physical systems in which these things are embedded—“the city” and its towers, with repeated mention of a labyrinthine “minoature”. And this city is full of violence / surveillance—tenements waking up, cops forging evidence, and rockets exploding in the sky. All of these ideas feel connected to me in this book—for you, how are violence, architecture, and surveillance related?

MC: Surveillance and architecture are both integral to the maintaining of contemporary power structures. They control the movement and behavior of bodies through a space. Architecture determines your route, and surveillance records your interaction with that route. The city combines these tools with an overwhelming density. There is this way that surveillance seems to be the secondary function of most contemporary technology as well. Phones record the path you’re walking to work everyday or where you’re going out to eat. Your laptop is recording what sites you visit and what products you’re buying, or even just looking at. It feels impossible to conceal yourself fully. But even then, it seems that surveillance is for the most part a strange formality. Most of this information never really gets used. Google recorded your hike and stored it, although it’s unlikely that anyone will ever look at that. But in that refusal of privacy there is a potential violence. There is this looming threat. The hypercapital will always know what you want and where you can buy it. These systems for the most part just flaunt that fact, so that when they actually use it, you think it’s normal or unavoidable. Maybe the point I’m circling here is that architecture and surveillance normalize violence.

AH: Lastly, what is the role of dreams in your work? Throughout the text, dreams are mentioned and explored in many ways – not having dreams, wishing one could have dreams at a certain time, being questioned about one’s dreaming. Even finnegans wake, that crucial avant-garde work about dreaming, is alluded to. Yet I would not quite call this involvement with the dream literally surrealist, but as almost the removed sign of surrealism, or surrealism emptied of its content—the question, “any dreams?” repeated over and over with answers in the negative. It’s kind of an anti-surrealist or post-surrealist approach to dreams, wherein the very language we use to talk about subconscious experiences stands in for the dreams themselves.

MC: I rarely ever have dreams, or if I am dreaming, then I don’t ever remember them afterwards. The few that I do, don’t feel like dreams, they feel more like fake or false memories. Like I’ll have one of a friend making plans with me or of a conversation with my mom, and it’ll be believable, and then I’ll wake up and realize that it didn’t happen. Or it’ll occur to me later that it was definitely a dream. So my experience with them is as this slight mottling of reality—a minor distortion. The phrase ‘any dreams’ is almost a confession in my eyes. When you say ‘no’ you are admitting to some extent that the book’s strange reality is real and that all of these things that you’ve said and done are real.

I like this label of the post-surrealist. When I was starting to work in this kind of wonky / abnormal space, people would often assume that the work was about dreaming or about a character on hallucinogens and it always frustrated me. It feels like such an easy / lazy out to say that it’s all in someone’s head. But to me there’s so little interesting about that. I am infinitely more drawn towards this world of anomalous acts. So maybe the ‘no’ is also a refusal of those interpretations.

AH: One more fun one: what’s a work of art or writing you feel ambiguously about, something that you could not earnestly recommend, but which still provokes something in your practice as a writer?

MC: Ha. I love this question. I play a lot of old video games. Stuff from the early 2000s like Deus Ex or Omikron or Gorky 17. I’m really drawn toward the aesthetic of low-poly graphics and the kind of campy writing that was so ubiquitous. There’s something so mysterious and interesting to me about these strange flat surfaces with warped textures mapped onto them or these weird little assemblages of jagged shapes that you are supposed to view as a person. Often these games will have some seams showing. I’ve had a lot of fun clipping outside the play area or trying to sequence break. It opens up this access to an otherworldly kind of backrooms area. But to answer more specifically about something I couldn’t recommend, I recently finished playing the PC port of Metal Gear Solid 2 and it was pretty rough. The game has a lot of interesting anxieties about surveillance and American intervention and nuclear weapons, but also the controls for that PC port are disgusting. It feels like mashing broken fingers against a keyboard. But the way that game (that series) tries to explore these ideas definitely had an impact on me. It’s helped fuel my continuing interested in visibility / concealment / surveillance. The way that those concepts can happen in media or be exhibited as elements of said media. Like a text trying to conceal itself or trying to make itself more visible. Or anti-surveillant somehow.

Ava Hofmann is a trans writer currently living and working in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. She has poems published in or forthcoming from Poetry Daily, Black Warrior Review, Fence, Anomaly, Best American Experimental Writing 2020, The Fanzine, Datableed, Peachmag, Always Crashing, and Foglifter. Her full length collection […], is forthcoming November 1st, 2021 with Astrophil press, with more books on the way. She also runs SPORAZINE, a magazine of experimental writing written by trans people. Her website is www.nothnx.com and her twitter is @st_somatic