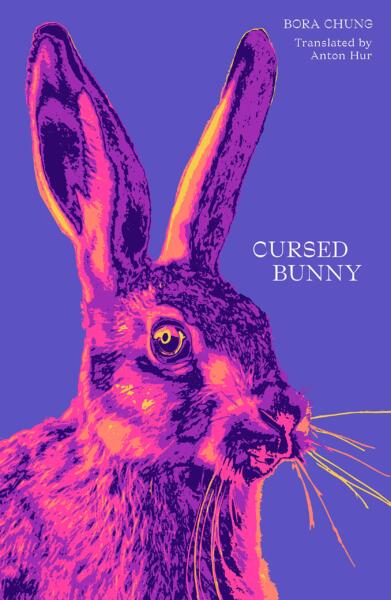

“The bunny nibbled away.” Everyone is talking about Bora Chung’s English-language debut: Cursed Bunny. A haunted toilet, an unexpected pregnancy, a cursed rabbit lamp, a car accident, a fox that bleeds gold—nothing is as it seems in these darkly funny and super-obscene short stories. Look no further than the collection’s first story, “The Head,” in which a woman without any children discovers a gurgling, menstrual blood-smeared head in her toilet calling out to her: “Mother?”

“I only want so little,” the head hastily added, “I’m only asking that you keep dumping your body waste in the toilet so I can finish creating the rest of my body. Then I’ll go far away from here and live by my own means. So please, just keep using the toilet like you always have.”

Devastated, the woman quickly learns that the talking head has been using the woman’s shit to slowly build a new body. In Anton Hur’s translation, Chung approaches the mediumicity of the body with enticingly excessive language—a poetic wastefulness—until a new assemblage emerges. This new form—or anti-form—that’s always springing up in Chung’s stories often disrupts not only the narrative, but a heteronormative status quo. Much of the tension in Cursed Bunny surrounds marriage, tradition, and even nationalism. Bodies don’t do what they normally do. Neither does blood. Or toilets. A place for waste becomes a place of growth.

All 10 of Chung’s stories feel very different, yet clearly connected by supernatural happenings, horrific excess, and existential unease. For example, “Snare” could be described as an ecologically driven fairy tale with much Cronenbergian flare,

Until he stopped bleeding gold from his forehead, his son continued to messily slurp away at his sister’s blood on his fingers and around his mouth.

The man realized what this meant.

whereas it feels more appropriate to approach a story like “Goodbye, My Love” as a work of SF:

S12878 and D0068 face each other. They touch foreheads. The capillaries on their faces—lines of their subdermal circuitry—light up in blue on the S model and sparkling green on the D. A pretty and uncanny scene that never fails to dazzle me.

I must also note the efficacy of Chung’s deceptively simple opening sentences: “She was about to flush the toilet”; “The bleeding refused to stop”; “Grandfather used to say, ‘When we make our cursed fetishes, it’s important that they’re pretty'”; “The boy was dragged into the cave.” Story after story, we arrive at some terrible new mystery. After every opening sentence, readers find themselves immediately asking, Why? Additionally, these opening sentences are often immediately complicated by enticing juxtapositions:

She opens her eyes.

Darkness. Pitch black. Like someone dropped a thick veil of black over her eyes. Not even a pinpoint of light to be seen.

Has she gone blind?

She tries moving a hand in front of her face. There does seem to be a faint object there. But nothing she can clearly discern(“The Frozen Finger”)

Given the challenges a grotesquely imaginative author like Chung might pose to a translator in terms of character range and versatility, Anton Hur has successfully rendered Chung’s psychologically complex worlds—of the living and the dead alike—with admirable dedication.

Paul Cunningham is the author of the The House of the Tree of Sores (Schism2 Press, 2020) and his latest chapbook is The Inmost (Carrion Bloom Books, 2020). He is the translator of Helena Österlund’s Words (OOMPH! Press, 2019) and two chapbooks by Sara Tuss Efrik: Automanias Selected Poems (Goodmorning Menagerie, 2016) and The Night’s Belly (Toad Press, 2016). He is a managing editor of Action Books, co-editor of Radioactive Cloud, and co-curator of the Yumfactory Reading Series. He is a PhD candidate at the University of Georgia. @p_cunning