Candice Wuehle: Your recent collection, Anti-Heroines, navigates between a number of fascinating genres or modes—wisdom literature, grimoire, a series of epistolary poems addressed to the moon, epyllion, and…more! There’s even a version of a panel presented at the 2018 American Comparative Literature Association. Can you say a bit about how you chose these particular modes? How do they function differently throughout the book or compliment one another?

Lo Ferris: So, part of the answer is accretion, having written pieces over the course of several years, mulling over a sustained aggregation of impulses and having them come out in different ways.

Another answer:

The original goal of the project had been to create “the critical edition of Lucia Joyce’s lost novel.” This was always a quixotic element to this attempt, because, of course, the manuscript of Lucia’s ostensible manuscript is lost. I went back and forth about how seriously to take this, and pretty quickly knew that I wasn’t actually going to write a simulated novel. The form of the book was the best I could do to reflect that inherent loss, the absence of the novel.

Also, this form reflects my sensibilities as an artist and reader. The poetics of the blog, of fragments being held together by a continuity of artistic effort sustained over time. For example, Kate Zambreno’s Heroines began on her blog Frances Farmer is My Sister. (By the way, I did of course read Heroines many years ago and it is a distant influence. I only remembered after titling my book the implicit reference to hers.)

CW: Anti-Heroines incorporates your own translations of interviews and letters written by Lucia Joyce, much of which I believe were gathered during your research at the James Joyce Foundation in Zurich. I was moved by the way these translations act as a sort of confrontation with the “regime” of English. How did these translations become a part of Anti-Heroines?

LF: Part of this was the reality of documents relating to Joyce. Her first language was Italian, then French, some German, with English learned along the way. This reality also made me reflect on my own bilingual childhood. This was part of my approach to the text. For example, I wrote a poem in Spanish and translated it—I actually have some early drafts with more of the work in Spanish translation, but decided it wasn’t the right fit for this particular project.

CW: In addition to Lucia Joyce, Anti-Heroines also considers another under-remembered artist, the French surrealist Claude Cahun. What drew you to the life and art of Joyce and Cahun?

LF: This was part of the development of the project: I became frustrated with trying to recoup the tragically lost output of a closeted queer artist and thought it fitting to look to queer women and non-binary artists at the time who actually did leave artistic legacies. The main two that end up in Anti-Heroines are Claude Cahun and Hélène Vanel, an even more under-remembered artist. The form of “Epyllion,” which is the main content of the Lucia Joyce section, was inspired by Claude Cahun’s Héroïnes.

CW: I was really struck by the final piece in Anti-Heroines, which seemed (to me) to be a hybrid of autofiction and autotheory that comments directly on the autotheoretical gesture in the lines, “To write autotheory is to retranslate a ‘theory of the self’ in the regime of English. The theory of the self is also a ‘body-essay’ in English translation.” Later on, this speaker asserts, “The body essay, you see, is my last hope.” How did autotheory enter this project? How does autotheory generate “hope” where other genres have failed?

LF: Left to my own devices, autotheory is the only thing I can reliably write. It’s my natural mode, I suppose. So I was always writing something like “autotheory” or “autofiction” even before I became acquainted with them as genre and lineage. The hope of the “body-essay” is in the body, the continued life of people who can write, a physical act.

CW: Relatedly, in our correspondence leading up to this interview, I was excited to learn you’ve recently completed your first novel, a work of autofiction. Can you tell us about this project?

LF: My novel, Zog, really sprung up alongside my work editing this book, actually. The project began when I was re-exploring this personal archive and remembered an old secret admirer of mine who started commenting on my blogs and then my best friend’s blog when I was in college in 2010 and 2011. The commenter, who went by Zog Kadare, offered pointed, accusing psychoanalytical and philosophical glosses in an inscrutable style on more personal, cryptic posts, and my best friend and I always suspected we knew them in real life but couldn’t figure out who it was. Zog’s behavior escalated in unsettling ways and eventually led to me making my blog private permanently. I had mostly forgotten this! Zog the novel came into being when I set myself the quest of trying to find out the identity of this mysterious interlocutor and (re?)discovered that they’d also created a small corpus of experimental fiction and critical writing.

The project had always been conceptual, creating plot out of my real-time investigation, but discovering Zog’s corpus invited further narrative intervention and engagement. The novel as a whole was a great opportunity to pursue my commitments to various psychoanalytical schools and writing through trauma, the poetics of genres like the personal blog, confessional emails, fanfiction, or the IMs that were the sort of “girl artist” mediums of millennials. Looking back on that time now when “Tumblr aesthetics” have been surpassed by many other currents felt valuable to me because it felt like I was contributing something to the backstory of today’s, well, online “girl” for some diaphanous value of “girl.” I think there’s a lot of tenderness between terminally online millennials and the “new” youth and their “new” mediums, and I thought there was something almost wholesome—in a rather harrowing novel—about being able to create sustained work out of the desperate, vivid chaos of being young and online in a different time. The novel also draws from my personal fondness for the anti-detective novel. Some notable books I read alongside this were Cristina Rivera Garza’s La muerte me da and Verde Shanghai, and Ottessa Moshfegh’s Death In Her Hands. I’ve considered billing it as “the worst detective novel I could write” or “alt lit trans babe strikes back.”

CW: Garza and Moshfegh are both absolutely fascinating and that idea of telling a story that isn’t one is so ghostly to me. You know—the idea of the body that isn’t there, the corpse we frantically try to reanimate. This idea of “re” “animation” and the occult makes me think of the way tarot card readings direct, disrupt, or generate the flow of several poems in Anti-Heroines. I had the sense at points that Anti-Heroines was actually taking advice from the tarot on how to be a book or which directions to unfurl in. How do devotional or occult poetics figures into your work?

LF: It’s really funny you noticed that, because I think I didn’t notice that, but you’re right. The real answer of course is that the Tarot disrupts because I was actively reading the cards throughout. It’s a part of my way of being. The term “occult poetics” is very interesting to me. I would say the closest my poetics turn to the occult is in mediumship. I often do feel like I’m possessed by projects. In the course of writing Zog, the novel, I did a deep dive back into Jack Spicer—an early influence—remember how the collected poetry came out in 2008!—and was newly struck by some of his lectures on “dictation” and poetry. I think this is very close to my own position, that there’s something—at least experientially—in writing poetry that feels like it’s emerging from the aether, making use of your material, “building blocks for the Martians,” as Spicer would say.

I think many occult and devotional practices are excellent tools for communicating with “Outside.” It’s not a substitute for assembling your “building blocks” but it can certainly offer an invitation, open some space. I bet you and I, specifically, could probably go back and forth happily for hours on how to balance the movement of the psyche and the demands of rigorous aesthetics!

CW: Absolutely. I specifically think of this in relation to how time flows through the body and turns into memory and of the body as a sort of flesh radio whose signals distort (or clarify), which actually leads me to the way Anti-Heroines considers but also incorporates time and memory. The collection is divided by season as well as by specific dates, which really emphasizes the sense of personal and historic scope this collection exists in. Do you see these elements impacting the structure of this collection? Or, to put it differently—and much more vaguely—what do time and memory mean to you as a writer/archivist/translator?

LF: This was partially a manuscript strategy—it occurred to me that there was something significant about how the work had accumulated over time and, finally, I thought a chronological approach had the advantage of being a bit more recognizable and simple and would be a welcome contrast to the stylistic variety of the work.

Time and memory are everything to me as a writer, actually, because I think they’re the most elusive enemies of literature. Capturing the passage of time is an extremely difficult feat, and I feel like most writers are trying to contest this difficulty. Memory likewise is extremely difficult for the literary. It’s like the final boss.

CW: The final boss. I love that phrase—it sounds to me like the plane where TLC television shows meet Lauren Berlant. Thank you for speaking with me, Lo! This was a delight.

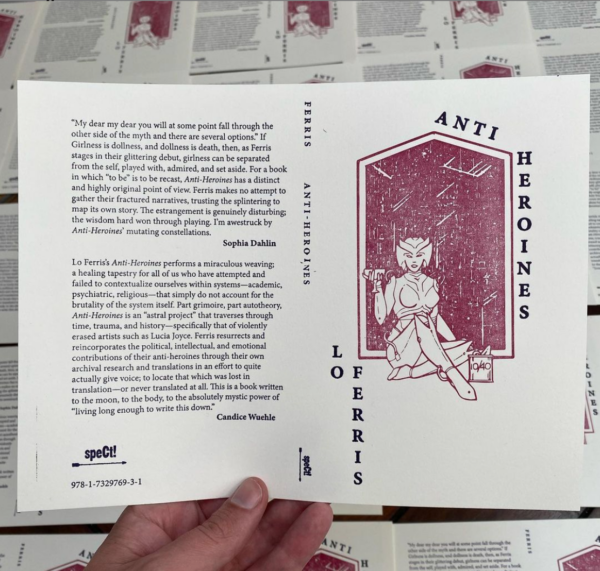

Anti-Heroines is now available for pre-order from speCt.

Lo Ferris is a poet, writer, and translator local to Oakland, California. They are the author of Anti-Heroines (speCt! 2021), and their work has appeared in Fence, Bombay Gin, The Atlas Review, and Prelude. They have an MFA in creative writing and literary translation from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Keep in touch on Twitter or Instagram: @lo_k_ferris

Candice Wuehle is the author of the novel MONARCH (Soft Skull, 2022) as well as the poetry collections Fidelitoria: Fixed or Fluxed (11:11, 2021); 2020 Believer Magazine Book Award finalist, Death Industrial Complex (Action Books, 2020); and BOUND (Inside the Castle Press, 2018). Her writing has appeared in Best American Experimental Writing 2020, The Iowa Review, Black Warrior Review, Tarpaulin Sky, The Volta, The Bennington Review, and The New Delta Review. She holds an MFA in poetry from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and PhD in Creative Writing from the University of Kansas.