“The inner landscapes ignore humans. They do not communicate like us. In this way, they are reminiscent of any place in nature.”

-Aase Berg on her “ur-landscapes” (from Tsunami from Solaris, translated by Johannes Göransson)

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about Aase Berg’s thoughts on what she calls the “ur-landscapes” of her poems. Especially when reading Kate Durbin’s Hoarders (Wave Books, 2021) and Evan Isoline’s Philosophy of the Sky (11:11 Press, 2021). Both books approach humans—and the lyric “I”—as a presence/absence. In Durbin’s Hoarders, the hoarded material—an excess of objects—usurps the human resident. The effect arguably exceeds juxtaposition. The “I” is nearly replaced by the human, exhausts the “I.” For example, one focal hoarder named Craig (“I’m Craig”) quickly becomes “tattered American flag next to a boot” and a narrative emerges as we read the objects. Cathy’s introduction (“I’m Cathy”) is juxtaposed with “rhinestone tiara.” As ur-landscape, Craig’s non-human representation consists of rotting encyclopedias, antebellum clothing (covered in “black dust”), Nazi regalia, German beer steins, a baby doll face “ripped from the body with no eyes.” By including italicized quotations, Durbin further contextualizes Craig’s objecthood for the reader. Like a child in Lacan’s mirror stage—trying to locate a register of the Real—Craig, who has gone “weeks with / out a bath, weeks without changing” his shirt, is both surrounded by and reflected in objects. Those objects become mirror. Ur-landscape-as-unconscious mindedness:

My daddy was a soldier in World War II and served in the elite

SS troops black and white photo of a young, smiling man in a

Nazi uniformHe was from a long line of butchers, a long line of soldiers, a long

line of white Jesus in five foot oak frameAll my daddy ever wanted was a boy baby doll face ripped from

the body and no eyes

(54)

Then there is Cathy: who consists of faded Space Jam bedsheet, pink medicine ball, coffee pods, Olaf the snowman oven mitt, and more. If the reader isolates the objects from the italicized quotations, the objects still mirror, communicating posthuman sign activity. The landscape does not “communicate like us” as Berg might say, but it does offer a fragmented reflection of the hoarder. Durbin’s poetry reveals how the counterfeit or reflection (“Target puzzle of a painting of a snowy cottage”) is what both liberates and victimizes human imagination.

In “Noah & Allie,” Durbin clues us in on an absence (“Disappearing Floor”) that is also a presence:

My husband Noah and I have been married for forty-two wonderful, crowded years Noah’s plaid tie tucked in The Canterbury Tales for a bookmark; Allie’s plaid shirt stuffed on a shelf between Nancy Drew’s Clue in the Diary and Hardy Boys’ Disappearing Floor (73)

Language in Hoarders functions as arguably useful clutter. A compact clutter-thought language. A language of memories, desires, ambitions, and dreams. Clutter becomes a way of reading/translating suffering. Durbin’s object-flooded interiors become stand-ins for the actual human inhabitants. The human names and identities not only feel dependent on how we read the objects, but also how Durbin has insightfully arranged the objects into narratives. Hoarders‘ excess also expresses and explores a recognition of loss, regret, and even, at times, shame. One of the most gripping moments comes in the section titled “Shelley,” in which Durbin hones in on a Barbie Dream House:

My hoarding has left my family in debt and my house in disre-

pair shelf of Barbies with disheveled hairLast couple of years we’ve had a problem with the Barbie Dream

House with a pink plastic roof (43)

Throughout Hoarders, Durbin’s line breaks take the reader by surprise (i.e. a literally broken instance of “disre-/pair”; a problem with an unattainable “Barbie Dream” notion of fame or celebrity). In Hoarders, it only feels appropriate that the “Andy Warhol Barbie” and its proximity to the Warhollian so on and so forth—the seemingly infinite photographic repeat—implied by the “etc” that appears in the same final line. The last word in “Shelley.” The horror vacui of museum gallery-like space of another hoarder’s home/story.

Objecthood could be thought to be functioning as a new kind of selfhood in Hoarders. Or at least a way of understanding a selfhood at odds with its self in the form of objects:

I don’t want my children to have a broken home Thomas Kin-

kade for Target puzzle of a painting of a snowy cottage, windows

aglow with golden light

It reminds me of Umberto Eco’s comments about a full-scale reproduction of the Oval Office inside the wunderkammer-like Lyndon B. Johnson Library. From Travels in Hyperreality:

To speak of things that one wants to connote as real, these things must seem real. The “completely real” becomes identified with the “completely fake.” Absolute unreality is offered as real presence. The aim of the reconstructed Oval Office is to supply a “sign” that will then be forgotten as such: The Sign aims to be the thing, to abolish the distinction of the reference, the mechanism of replacement. Not the image of the thing, but its plaster cast. Its double, in other words.

Is this the taste of America?

“I’m going to make something that makes me.

I’m going to create a monster.”

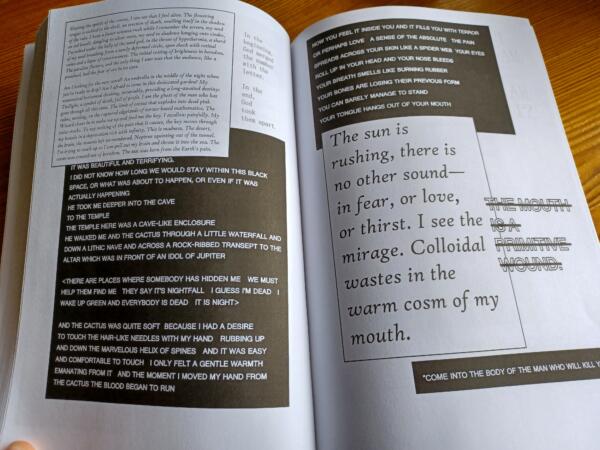

While the human subject feels distant from a body or vessel in Isoline’s Philosophy of the Sky, it also reads as more monstered than some of the subjects of Durbin’s poems. The simultaneous presence/absence of humanity in this book felt similar to my own first-time experiences of exploring the haunted interiors of Blake Butler’s EVER or the glitch-glitz gore of Cronenberg’s Videodrome:

A thing I am, a creature

an act I do

an eye I see

an object I become

I see myself in everything, in every thing

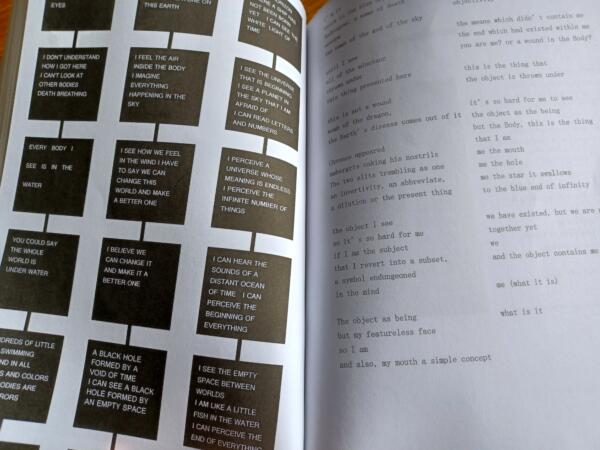

The autonomy of Durbin’s ur-landscapes is signified by object-subject relations, whereas Isoline’s book itself (and its design) becomes its own dizzying ur-landscape of unpredictable collisions, allusions, and visual booby traps. Isoline’s language—an excessive clutter-language like Durbin’s—is consistently demonstrative of a kind of hoarding (“A THOUSAND MILLION NEURONS”; “A THOUSAND TRILLION GALAXIES”; “A THOUSAND MILLION YEARS OF EVOLUTION”; “SEVEN BILLION, BILLION, BILLION OF THE ATOMS IN MY BODY ARE / NINETY PERCENT OCEAN AND TEN PERCENT STAR”).

Philosophy of the Sky also contains no page numbers. It’s more “simulation” than book, as author Gary J. Shipley has stated. The lack of page numbers make the experience feel less like reading and more like one is bearing witness to a mutation. The way a cell divides, multiplies. A mutation, a revision of interiority.

More accurately, the so-called lack of page numbers is not “lack.” I, as reader, have been conditioned to believe in page numbers as something necessarily Real. But “lack is not real,” writes Isoline.

There is only abundance:

Each of Durbin’s Hoarders poems feels like an art gallery. Isoline’s Philosophy of the Sky behaves in similar ways. Page after numberless page, installation after shark-infested installation, Isoline’s landscapes feel reminiscent of Lynchian environments consisting of new, uncanny ideas of body as opposed to cohesive, recognizable bodies. He writes of “monstered” objects that inspire “horror and disgust / and love inside the fetishist.” The excess offered by Isoline’s oceanic abjection is precisely what the reader (or fetishist) desires. The idea of an original breaks down in Philosophy:

But lack is not real

and I will show them my proof, my monster

weaponless

in the ocean of the sky

The reader-fetishist, ever-desirous of the Real, is at the mercy of ur-landscape. Like it or not, it unfolds like “a-thing-that-looks-like-you,” but it is not you. This form of abjection, as Madison McCartha has suggested, is perhaps something better described as “in between”:

Becoming the border between self and other offers another way of inhabiting the racialized surface Hartman describes; but while the abject, indeterminate state endured by the body can be world-shattering–this exceptional “faint” Kristeva describes is by no means out of the ordinary. On the contrary, abjection is both a normalized feature of, and even common to the experience of being racialized, institutionalized, instrumentalized, and mediated—indeed, of being used—by systems of power under which the self cannot be defined as either subject or object, but as something in between.

Perhaps to best explore this in-between is to monster or mutate ideas of self.

Much later in the book, Isoline writes:

An object that is a living thing

a-supersense

a vegetable you plant with your teethan-other

a-thing-that-looks-like-you

a-thing-at-the-other-end-of-thatan object which appears to be floating

an object which stops moving when you touch itanxiety about what will happen next

an object that seems too real to be realsomething-happening-on-a-neuro-cellular-level

sparks pouring from the eye of a cephalopod

dopamine-trees

Again, Berg says the “ur-landscape” or “ur-place” of her poetry is not static. Her ur-landscapes do not necessarily prioritize humans. They are more reminiscent of any place in the natural world. Such landscapes—like Durbin’s and Isoline’s—are perhaps better approached as haunted interiors, uncanny rooms “full of ghosts.” Snapshots from planet Solaris.

Paul Cunningham is the author of the The House of the Tree of Sores (Schism2 Press, 2020) and his latest chapbook is The Inmost (Carrion Bloom Books, 2020). He is the translator of Helena Österlund’s Words (OOMPH! Press, 2019) and two chapbooks by Sara Tuss Efrik: Automanias Selected Poems (Goodmorning Menagerie, 2016) and The Night’s Belly (Toad Press, 2016). He is a managing editor of Action Books, co-editor of Radioactive Cloud, and co-curator of the Yumfactory Reading Series. He is a PhD candidate at the University of Georgia. @p_cunning