Paul Cunningham: What led you to girlgirl? Did it begin with a particular image? How was she conceived?

Kim Koga: I started writing girlgirl, I think, somewhere around 2014. It had been years since I wrote and I was looking for something inside myself. I was thinking a lot about politics, heroes and heroines, superheros, Don Mee Choi’s The Morning News is Exciting—love the language in it, and Alice Notley’s The Descent of Alette. I had long been very excited by the feel of the language in Don Mee’s poem “Manegg” and Hawaiian pidgin (my parents grew up in Hawai’i & I still have family there). I wanted to use speech and patterns/structures to create a sense of foreignness that I felt/feel as I exist in places where I don’t fit—not growing up with any Asian friends and I stick out like a sore thumb always being asked “where I’m from”. When I started writing her, I wanted to start from an invocation and a birth, most of which I’ve discarded, where she can be birthed by the world—a dedication to mother—as the concept of a mother not a specific mother, to discover/uncover/write into girlgirl.

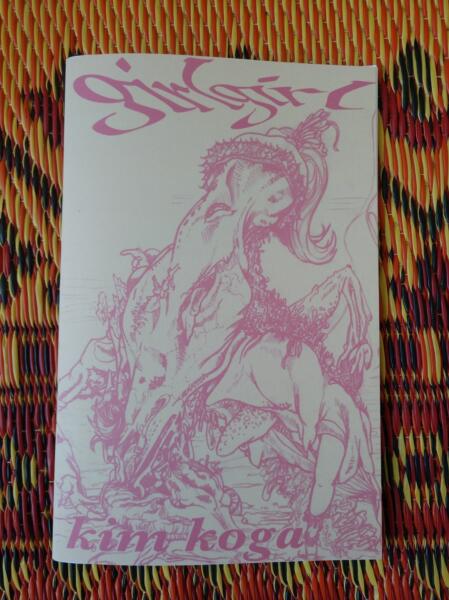

Inside my head I saw her as this superdeformed anime type girl—super cute, but also with an eye hanging out of her face and bangs in her eyes. She’s super cute and takes the form of this stereotypical anime girl—playing into a stereotype she passes as the convention that society expects of her but breaks the sidewalk where she walks and bursts asphalt as she passes; she boils from the inside. She has companions: teddyteddy, skinbag, pinkpink who are all a part of her costume and body and performance.

I let her (girlgirl) sit for a while and she slept inside my mind and after the 2016 election, she boiled up in me again—and I saw her bloom inside me—show herself to me more than I already knew. She’s a spy infiltrating a war in a post-apocalyptic landscape—she’s on reconnaissance missions, sabotage runs—as an army of one. While she destroys, she’s also this sense of/thread of anti-war, anti-violence too.

PC: girlgirl, with all her fabulous “pinkpink” and generative “skinbag” flaps and orifices, strikes me as an assemblage that also reimagines acts of looking (“piss a look”; “eyeball sung”) in order to undo the self. What is girlgirl looking for? Is girlgirl a kind of architecture from which narrative emerges?

KK: I think girlgirl is an aspect of myself—she is solitary with the companions composed of her body and performance . . . I think she is looking for survival—the means to survive and to create resources for everyone who lives beneath this surface in which the characters exist, into a space where everyone else who’s drowning might survive and then flourish. I think she’s looking to create a new world of all the creatures who don’t exist within dictated norms, if that makes sense?? She is literally looking for the spaces, small cracks in the world where she can squeeze her body into and then tear them apart.

I do think that she is her own kind of architecture from which the narrative emerges and that narrative feeds back into her and she feeds into it. Her language, which is the language of the poem, is a kind of architecture which creates the narrative too. It’s symbiotic and parasitic. Parasitic in that she is taking from pieces of and destroying pieces of others’ narratives in order to build a narrative for those who don’t have their narrative written or seen. And it’s symbiotic in that she gives voice to and empathy for those who she strives to help—they feed and support one another.

PC: girlgirl also feels like an extreme landscape. Her flesh is “torn” and she’s “got those blues.” It feels like she’s survived something and she’s trying to rebuild. Is this about the erosion of a body or the reinvention of body? Or both?

KK: I think it’s about both. I think it’s about loss and reclaiming space. These are things that I have struggled with in my life and it is something that I will continue to struggle with for the rest of my life. I think she is both within me and exists outside of me. She’s on her own journey to reclaim what she has lost and to allow her body to be both a generative, fecund space, and a space that’s fallow and filled with its own failings and death. Her body is a site of erosion in which it sloughs itself off as if her uterine lining is her epidermis, and she is allowed to purge all the manifest terror and failings of her body.

Throughout the poem I think she is able to reclaim more and more of her autonomy in her body, but she must also reconcile its limitations. I am not done writing the poem yet and she still has a long way to go but part of the extreme landscape that she travels through, in small part, is horror of her own body manifest outside of itself; and in a large part the horror of what the brain creates, and she is the horror of what the body endures.

PC: Repetition is a major part of girlgirl. Language spasms and scrapes the reader into pink. It’s leaky and dynamic. The sonics are dialed all the way up. The excess of girlgirl (even in the title itself) is hard to shake. It functions like a constant echo, just as girlgirl involves a constant expansion. What is this repetition—this excess—rebelling against?

KK: I think it rebels against everything that you were told is right and what is right about language—how to use it to express yourself or not use it to express yourself. It rebels against the secret languages of people and public ways that it’s mocked. Language creates so much of the self and it’s been stripped away from cultures/people who are forced to be one thing or another. I think of Kayo Hatta’s Fishbowl—a short film based on an excerpt of Lois-Ann Yamanaka’s Wild Meat and the Bully Burgers—in one scene these kids in Hawai’i in an English class in which the teacher tries to strip the pidgin from their language, remove their accent and force them to speak ‘properly’ but it’s also a stripping of identity and culture and pushes the idea that there is only 1 way to survive in the world and ‘make something of yourself’ which just isn’t true. By allowing the language to creep, expand, explode, and leak its excess everywhere it takes all of that language that was stolen from people’s mouths and spits it back into a poem, a book, and allows it to exist, breathe, reclaim space, and puke all over the success that it was told it could never have if it remained true to its origin (the mouth of the speaker from which it was stolen). Not that the language of the poem is Hawaiian pidgin—it’s not; it’s more of breaking language and allowing it to exist brokenly.

Kayo Hatta’s Fish Bowl (2006)

I think the word “girl” is so often used as a diminutive thing—meant as an insult, or used to talk down to someone. I wanted to double it up and put her back into something that someone determined that she couldn’t be. She takes her name from something that is doubly insulting, doubly cute, doubly child-like, doubly diminutive and sweet and exists as something that is cute but also with very hard edges that leak and bleed I get tired of feeling like the word girl is not ‘supposed’ to be used to talk about an adult; I’ve always thought of myself as a girl—I’m a girl. I want that language for myself. I want to push back against a feminism that denies me the word “girl” and denies all the complexities of being an Asian girl in the US.

The repeated echoes throughout the book is way to force the language to exist in a space where it’s not only in front of your eyes but talks to each other and you (the reader)—bringing it into a deeper conscious because as it echoes throughout the pages it also comes back to talk to itself—generating its own conversation between the pages and thus in a way, bringing that language, that voice back to life again.

I wanted the language to be very sonic and hard—many consonants, but also language that sometimes softens into a rhyme and resists it at the same time (like the line about a birth control machine) it feels like it both gives itself to the rhyme and chokes on it at the same time. It feels a little too cute for me, but it’s her language and it’s what she needs. It’s joyful, cute, rebellious, painful, shrieking, and powerful.

PC: What are you reading right now? Any recommendations?

KK: I recently read Melissa Febos’ Abandon Me—again. There is so much there that reminds me of the need in myself and ways in which I’ve broken and wanted to break myself. I am currently reading Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls by T Kira Madden. I am struck by how she captures her life as an adolescent and teen and adult, and find echoes of myself, and recognize the otherness of self. Lois-Ann Yamanaka’s Wild Meat and the Bully Burgers always makes me cry. Cynthia Arrieu-King’s The Betweens holds so much of my heart. And Kim Sagwa’s Mina (translated by Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton) is horrific and beautiful—I am reading it again right now.

Copies of girlgirl are available from Asterion Press. Purchase one [here]

Kim Koga is the author of Ligature Strain from Tinfish Press. Her work can be found in 1913 a journal of forms, Erotoplasty, Burning House Press, the tiny, and more. After completing an MFA at the University of Notre Dame and returning to southern Calfornia she started working in tech. Writing, making art, gardening, and maintaining a breadbox expand the loss of time. Her latest chapbook girlgirl is available from Asterion Projects.