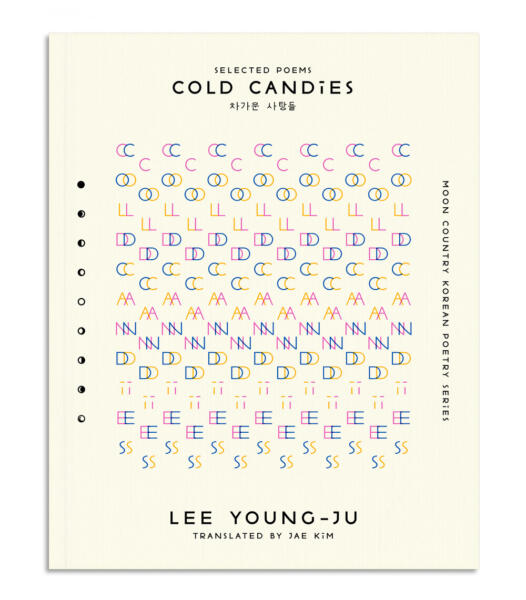

(Now available from Black Ocean’s Moon Country Korean Poetry Series)

In his translator’s note, Jae Kim states Cold Candies contains selections from four of Lee Young-Ju’s original books. Here, Kim has thoughtfully organized the translations into seven sections: “Sister”; “Roommate, Woman”; “Dyed Blue”; “Summer Mourning”; “Dear Monster”; and “Pillow.” Every poem of Lee’s is its own labyrinth. What we consider the ‘outside’ might actually be anything but freeing depending on a body’s own labyrinthine interior. A body might not even be aware of its own secret compartments. And what spills out of those secret rooms? Poetry’s stain. Death in/after life. “I dreamed I became a zombie with human principles,” she writes in “Exercises in Sentences.” Her poems are surreal and disorienting yet somehow familiar. Tinged with shades of red and blue, Cold Candies drips with the dough of sunlight, the hardness of moonlight, self-destructive dogs, shapeshifting dolls, alleyways, and basements.

I’m standing on the beach. I can’t move from here. I don’t have any rooms. Or I have too many. At times, goats on the island stop by the room I don’t have and leave through the many rooms I have. Their hooves leave behind evidence. Trying to write these stubborn stains that crumble like foam, I fall into a labyrinth (from “Guesthouse” 67)

The first section, “Sister,” introduces us to the alleyway—a dog-infested dimension that recurs throughout the collection—a mysterious zone where dolls (reminiscent of Hans Bellmer’s) grieve for limbs gone missing, where men snake about in the swirling “blond” yellow of celandines. In the nightmarish “Traversing Through the Wind,” girls cannot run, but they can float like broken necked “wildflowers.” In “Blank Notes,” girls “talk without moving their lips” and dress one another in gauze. As male figures continue to pose a threat, communication between girls—between sisters—becomes something increasingly physical. A system of touch that is often wet, damp, or warm:

I was fond of stories about the dead. Oil boiled on the stove as the sun set. I swallowed a gulp of water for each page. Sister stopped beating the cutting board and felt my forehead with her wet hand. She’d closed the restaurant for good. Meat thawed slowly in storage.

(from “If You Are Carnivorous,” 39)

With one ear buried in the pillow, Sister wipes away the flowing blood. There is a dark and wet aesthetic part of my dear sister, you see. My heart pounds when I think that no one will find it.

(from “Sealed,” 52)

“May the back alley protect me” prays the speaker of “The Girl Throws,” a deeply disturbing poem in which the deadly recorder-chorus of a middle school appears to blast a young girl apart, smearing her blood all over its walls. The girl is also missing a tooth, appears to have been victimized by someone. Given the poem’s references to alleyways and hangers, one might feel compelled to read “The Girl Throws” as an abortion allegory. However, in a much later poem (“The Winter Lumberjack”) the alleyway is described as a place where “hit and run” happens. Lee might be possibly referencing her own tragic “hit and run” accident (which we learn about from Kim’s translator’s note). In any case, this poem—like many of the others—contains a secret.

Let’s not suffer, he said. Let’s read and regurgitate.

(from “Book Club,” 26)

In “The Girl Throws” the girl with the missing tooth describes herself as “ill” and swallows a razor blade. She then aligns herself with trees that “can’t bandage their aches.” Trees, like humans, tend to suffer in Lee’s poems. They are cut, burned, surrounded by trash, etc. Trees and humans alike feel disrespected, discarded, exiled. Helpless as a tree, the girl in “The Girl Throws” prays to the alley. Spends her time waiting for the future by looking toward the sun for warmth. In the end, she finds herself on a “hanger at the cleaners.” There’s no easy answers in Cold Candies—only secrets. The poem’s title itself suggests this, leaving us asking: What does the girl throw? Does she throw up? Is she forced to expel her self? What is a self in these poems? Additionally, the blood-red leak of “The Girl Throws” is quite the contrast to the blue-blood interior of “Intimately.”

Falling asleep next to me, carrying my sleep beside me were beautiful geometries. I drooled on the hemp blanket on those warm nights, and the slobbered, wet blanket slid down past my feet. It crawled out to find the lover’s facecloth tucked away outside the door. My feet were bare. Blue blood ran through my soles, and I felt strangely confident that the clouds could be touched if I managed to fall asleep.

(from “Intimately”)

In the poems of “Sister,” the interior is what always eventually leaks. In fact, in the title poem, Lee calls this “damp, decaying” interior: “Sister.” The leak continues throughout the collection. In a later poem (“Anniversary”), the speaker says,

The souls who died unfortunate deaths purify themselves by drinking water that allegedly cleans their memories—but I spill mine.

Pain and suffering is what spills from these wounded bodies. The hidden truths of their tortured interiors cannot be contained.

In the “Roommate, Woman” section, the “Sister” and the basement of leaky language returns as a body-rearranging, house-disappearing flood. “A Girl and the Moon” opens with a little girl calmly telling her mother that a strange ladder-like bone is growing from out of her back. She worries about the rest of her bones, too. She worries about the hardness of moonlight:

saw it off, Mother, please.

There are a number of instances when Lee’s speakers return to the growth of the ladder-like bone (or the implied removal of a tail—later associated with a “wound”). At times, the girls of these poems take on dog-like attributes. Given the role of moonlight and the strange bone-growth in “A Girl and the Moon,” one cannot help but think about werewolves throughout this collection:

White light pours out of Mother’s back. Only then do I bark, cackle until my throat stings. The sound that a hard rain makes.

(from “Summer Mourning,” 59)

In “Roommate, Woman,” Lee also positions the reader “face-down” on the floor of a tavern, often moving our eyes up and away from the floor. It’s as if we’re underwater, but we can’t look away from the moon. It’s as if we’re moving up and down at the same time. Up the girl’s ladder-like bone, up like the smoke coming from the soles of a barefoot child. But what’s that under your foot? The poem leaves us bobbing up and down after the floor floods, disappeared by what began as a “trickle” coming from a man who decided to write “everything.” And what accumulates in this everything? Only that which eventually vanishes.

While we sit on leaking fuel tanks and watch the pale clouds, our joined hands slip out the door. You pick up one of my eyes worming under your foot. It may snow. Snow (not an eye) like the bandage around my hand, smeared in crimson light.

(from “Roommate, Woman,” 31)

Like the alluring darkness of a basement or alleyway, Lee proves the prose poem remains an undeniably irruptive force. A sublime portal that offers anything but direct access to the mind of a poet. The “beautiful geometries” of her images destroy clarity and transport readers to an excitingly monstrous surreality. A provocative exploration of violence, selfhood, and grief.

Paul Cunningham is the author of Fall Garment (Schism Press, 2022) and the The House of the Tree of Sores (Schism Press, 2020). His latest chapbook is The Inmost (Carrion Bloom Books, 2020). He is the translator of Helena Österlund’s Words (OOMPH! Press, 2019) and two chapbooks by Sara Tuss Efrik: Automanias Selected Poems (Goodmorning Menagerie, 2016) and The Night’s Belly (Toad Press, 2016). He is a managing editor of Action Books and co-editor of Radioactive Cloud. He is a PhD candidate at the University of Georgia. @p_cunning