VI KHI NAO: How is your toilet?

PAUL CUNNINGHAM: My toilet is now in its proper place. Thank you for asking.

VKN: Usually I don’t begin with such a private inquiry on such a fixed receptacle, but why not here, yes?

PC: That’s fine with me. It has been an interesting few days.

VKN: Tell me more about it. And, what you mean by “interesting”? Interesting as in chaos/turmoil? Or interesting as in excitement?

PC: I moved (again) this past fall. After taking my first shower in the new place, the towel rack fell off and took three pieces of tile with it. After an investigation, the leasing office told me the condition of the bathroom was worse than they expected. In early January, I came home to a toilet in my kitchen.

VKN: Is there a poem of yours from Fall Garment that is similar to your broken towel rack situation, creating an unforeseeable poetic havoc for your collection? Or did all of your poems arrive to this collection in perfect form with no tension nor turmoil? What poem of yours that behaves similarly to a toilet in your kitchen?

PC: No, no—nothing really ever arrives for me in perfect form. As far as “unforeseeable poetic havoc” is concerned, I will say that the title poem of the first section—“Factory Appetite”—pushed things into a pseudo-autobiographical direction that I’ve not previously gone. So I decided to explore that a bit further. The “Factory Appetite” section was also the most recently completed poems of Fall Garment. The poem is about a glass factory in the town that I grew up in. Originally called Phoenix Glass, but the factory (ironically) caught fire four times and was rebuilt four times. This poem led to me examining my teenage years. So I guess this section was the most surprising to me because I’m not normally very personal in my writing.

VKN: How come? Auto-fiction, auto-poetry have gained traction in the last decade or so.

PC: I feel like the moment you say something like that, readers want to call you a confessional poet and start linking everything you write to you. So, I tend to avoid writing about myself.

VKN: The word “confessional” always makes me think of Catholicism. As if writing poetry or the poetic act is a confession booth between the priest (published material) and the sinner (the poet). Speaking of religion, your work is quite biblical—Eve appears with bourgeois Adam and she does something urethra-like, defacing his face with piss.

PC: Same! Yes, but I will say that the first section of this book isn’t entirely autobiographical, but I tapped into some of my past a bit more than usual to do this writing. I was thinking of Sylvia Plath’s “taproot” a lot during quarantine. As far as the piss, I was thinking of Warhol’s piss (or oxidization) paintings when I wrote that poem. Thinking of art as revisionary. As making new territory for oneself. I’ve also always been fascinated by Lilith.

VKN: Oh?

PC: Yes, Lilith is like an alternate version of Eve. From Judaic mythology. I believe that in one of the versions of the Lilith story, she refuses to lay beneath Adam because she views him as an equal. The story of Lilith feels very queer compared to the story of Adam and Eve. I made a short film about Lilith shortly after I moved to Athens, Georgia. A deeply homophobic person once prayed for my flesh in the middle of an Athens post office. This person was being extremely loud and confrontational about their support for Trump’s presidency. They were talking to a younger Trump supporter in line and kept repeating “Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve” over and over. Some other people in line at the post office got involved and were trying to defend me. I thought about this event for weeks. I ended up doing a sort of drag performance as Lilith in a short film I made.

VKN: Do you have a link to this film?

PC: Here it is. I haven’t really thought about this film in years:

VKN: Also, tell me more about this word “coenésthése” from page 25 of your poem. I tried to google it, but Google wouldn’t budge and Google responded with the following: “Make sure all words are spelled correctly. Try different keywords. Try more general keywords.” What words should I try?

PC: I am trying to remember.

VKN: I just watched your video while you were searching for the epistemological depth of that word. Your relationship with hand (yours and the sculpture’s), leaf (patterns), and skulls are consistent motifs here. I try to superimpose the images from your film to the contents of your Fall Garment—the transparencies appear solitary. Do you feel that your words are much more distinct than your films?

PC: I believe “coenésthése” is an earlier spelling of “coenesthesia,” which is a kind of hallucinatory inhabiting of one’s own body, including feelings that arise from multiple stimuli from multiple bodily organs.

As far as the distinction of my words versus my films, it might depend on the words/poems. The House of the Tree of Sores consisted of mostly prose poems. Some people have described it as a novel. However, I think I am inhabiting a more noticeably lyrical mode in Fall Garment. I would say my films tend to be more surreal. Growing up, I was very influenced by Kenneth Anger and Stan Brakhage. Because their short films didn’t necessarily need to have a cast. I’m also a big fan of Man Ray’s The Starfish.

VKN: Repetition provides a sonic texture for your work, but repetition (I leave the city/ to love my self // down the turnpike / in my high school uniform // down the turnpike / in the strange boy’s car //) can behave like prayers with votives and what not in yours as well. Tell me more about Kenneth Anger and Stan Brakhage. I am not familiar with their work.

PC: Both are experimental filmmakers. I would say I have a closer relationship with Anger’s films. Especially films like Puce Moment and Scorpio Rising. Are you a Lady Gaga fan? (I know you have that poem “Lady Gaga Apples” in A Bell Curve is a Pregnant Straight Line.) I believe she once paid homage to Anger’s Scorpio Rising with a jacket.

VKN: I am not anti-Lady Gaga—I just loved her name. It seems like a name born from a child’s mouth and stays there infinitely, in a loop of nonexistence afterwards. Such an aesthetic, sonic annihilation appeals to me greatly.

PC: I cannot remember how she altered her jacket. Anger’s jacket spelled “LUCIFER” in rainbow. Hers spelled out something different, I think. But I totally get what you’re saying about the name. I believe she has said her name was inspired by Queen’s “Radio Gaga”. Which is also a pretty repetitive song.

VKN: Are you / any Scorpio Rising in you? Or in any of your poems?

PC: I am a Scorpio. My sun is Leo. I can’t remember my moon sign. As far as my poems, probably the poem on page 32 is one of my more Scorpio poems. I was thinking about Mapplethorpe when I wrote that.

VKN: Are you a lobster?

PC: I fee like I can’t answer this question without thinking about Lanthimos’ The Lobster. Have you seen it?

VKN: I have. Scorpions are related to lobsters ( I think).

PC: That makes sense. I would say I most currently relate to a lobster.

VKN: Some of my favorite lines from your collection are “it was Triassic time/ so sic so /tri ass”—when you see the repetitious ass in dinosaurs. My favorite poem of yours lies on page 61. The last four lines: “his love/ a closet / a hiss of / gas”—I found “gas” surprisingly comforting despite its gaseous connotations.

PC: So, I’m not sure how obvious this is, but a couple friends have told me they knew right away, others did not. But “Sic Ark” is actually an erasure of Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park. I’ve never done an erasure before and I did not set out to do one. It just kind of happened spontaneously during quarantine. One of my students was very enthusiastic about Jurassic Park and I sometimes show the green Jell-O scene in my screenwriting unit as an example of suspense, pacing, anticipation, etc. One of my students suggested I revisit the novel and so I did. The novel ended up making me unexpectedly angry though.

VKN: Not obvious at all for me. Why did his novel make you angry? And, what was it like to cross out lines from his book?

PC: Because, I guess, Crichton spent like seven years working on this novel. Mostly during the 1980s. The novel very much consists of a continuous language of extinction. So even though it wasn’t what Crichton was setting out to do, all I could think about when I read this novel during quarantine was the Reagan administration’s disastrous handling of the AIDS crisis. I was thinking about that and the language of COVID-19. I had also taught Chase Berggrun’s R E D (an erasure of Stoker’s Dracula) several months prior to all the pandemic stuff happening. One day I just suddenly found myself crossing out sentences in Crichton’s novel. It happened very quickly and very spontaneously.

VKN: Was it an antidote to anger? Or did it fuel it even more?

PC: Yes, it felt like an antidote. And I wasn’t angry at Crichton, but I couldn’t stop thinking about the language of extinction in his novel. In this fictional book about resurrecting dinosaurs. While all these Republicans in the ‘80s were sitting around thinking the ‘right’ people were dying. I believe the novel came out in 1990, but was set in 1989. So I absolutely cannot imagine being a queer person in 1990 and reading that novel.

VKN: Did any of your friends die/suffer from AIDS or were the AIDS poems from your collection born from a place of Crichton rage/wrath/ire? I noticed from the footnotes that you may have done extensive research on this disease.

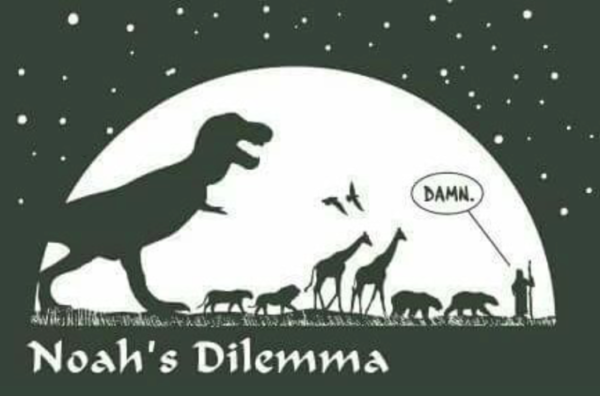

PC: I don’t have friends who have died from AIDS, but I do have friends who are HIV-positive. Yes, I did a lot of research about AIDS as I erased Jurassic Park. I wanted to include that research somehow alongside the erasures, so the footnotes felt important. I was thinking about the story of Noah’s Ark, too (and the Noah’s Ark-themed creationist theme park’s past discrimination against LGBTQ people). So when I erased the title—Jurassic Park—I was thinking about that “ark” sound and meaning as well as how “Sic” sounds like “sick.” But also how the term “sic” typically comes after a quotation or the reproduction of the work of another.

VKN: You must have this shirt then?

PC: Oh my god. LOL.

VKN: Your publisher (Schism)—they only publish men, yes? I was scrolling through the folks they publish predominately male writers. I mentioned “male writers” because it reminds me of religion again. Of something secular. The men are segregated from the women—the priests and the nuns.

PC: Not to my knowledge. I know they have published works edited by Edia Connole and she is one of the editors at Schism. They have published a large number of women in their anthologies. I am perusing the catalog now though. Yes, a lot of men. All I can say is that Gary J. Shipley believes in my work and I have had a very difficult time finding a place to publish transgressive queer writing. It feels increasingly like American poetry wants their queer writing to be tidy, moral, ethical, neat, etc.

VKN: And, you must feel deeply supported by them. Why do you think it’s that way? Neat? Tidy. Moral.

PC: I do feel supported, but it would be great to see more women authors published at Schism. I know they don’t solicit authors and they read submissions on a rolling basis. To respond to your other question, there just seems to be this pervading idea that “good” poetry is poetry that is accessible, relatable, honest (i.e. personae poems are “bad”). Readers want something that remind them of themselves, etc. I don’t want to read poetry that reminds me of myself. I liked what Fran Lebowitz said recently in Pretend It’s a City: “A book isn’t a mirror, it’s a door.” That philosophy works for me, but I realize it might not work for everyone else. Ultimately, a translingual book like The House of the Tree of Sores was a finalist in a lot of poetry contests, but no one wanted to publish it. Schism did.

VKN: Could men have a boys club for themselves? Outside of the context of politics? And, PR? Can beautiful things exist in isolation? Do you think it is naive or not coeval enough to have things—publishing things exist—without having to worry about equity for all the sexes? Is it possible for public things to exist without a thundercloud of sexism hovering over it, reshaping it?

PC: Possibly. I’m not sure. I know the Schism anthologies have featured women writers like Öykü Tekten, Amy Ireland, Alina Popa, Heather Masciandaro, Teresa Gillespie, Caoimhe Doyle, Katherine Foyle, and others. I also know that the kind of writing I’m doing (i.e. the butterfly/piss poem you mentioned earlier) would ‘never’ be published by certain publishing houses. Some editors want to publish queer writing, but it has to be a certain kind. Very accessible and optimistic. They don’t want to publish queer transgressive writing. A lot of journals (online or print) wouldn’t touch a poem like the one you mention, which is why I’m grateful that journals like Evan Isoline’s SELFFUCK exist. I do also write about personal trauma in Fall Garment, but I clearly don’t do it to appeal to certain presses. To be honest, I’m increasingly disgusted by how certain poets treat trauma like it’s a brand. Or use it to guilt people into buying books. It feels very trendy right now.

VKN: What disgusts you about it?

PC: There are poets I know with trauma who can barely read their poems aloud in a public setting. And that has been upsetting for me to watch. Because they are usually friends and I know it’s genuinely difficult for them to read those poems in front of a crowd. However, I think there are also people out there who think they have to write about their trauma in order to publish. Pretty much every poet I know has some kind of trauma. (I think that’s why so many of us are poets?) But I think it might also be dangerous to let your trauma become your personality. A quick example of what I’m trying to describe might be a conversation I recently had with someone: “Oh, did you like that book?” “Yes, it’s really great. It explores trauma.” “Okay? Is that the only reason I should want to read it? What are the poems doing beyond that? What about sound? Imagery? Language?” I guess I hate when casual conversation begins to feel like a point system i.e. This book is good because: trauma... This book is good because: gay author… I won’t speak for others, but I need something more than “You should read this book because the author is gay.” That’s not good enough for me. Tell me what the book is about.

VKN: I am curious about these last four lines of yours from page 15, “somehow i was always outside/the principal’s office laughing// somehow i always fell/ for a hometown mirage.” I really love those last two lines. “Hometown mirage.”

PC: The lines you bring up from page 15 are a reference to my high school experience. The town itself never felt like home to me. I was involved in many physical fights. Lots of bullying. Mostly about my weight or the way I carried myself. (I didn’t come out until I was 21.) I won most of those fights.

VKN: Tell me more about being bullied? How did you arm yourself from being ambushed? Did you train? What techniques did you use to win fights?

PC: I was just bigger. No technique really. When I was 14, I weighed around 230 pounds. It’s funny how if you’re fat you can spend a significant amount of your life being made to feel small. And then one day during eighth period gym class, you take everyone by surprise and start swinging back. It’s funny how things change after that.

VKN: Was it empowering? Or did you fear your strengths? Which poem(s) of yours reflect this empowerment? Which poem feel like you have extended your arms to take a swing at the world? Was it satisfying?

PC: I’m not sure I even really thought of it as strength. I think I just threw some punches at boys who never expected it. If it was satisfying, the feeling was only something temporary.

VKN: The phrase “hometown mirage” gives me the impression that there is a mirror somewhere in there. And, the last line of the page of the poem from “Factory Appetite”—has this line “i only know the tiny window where i sit/ steady mirror i call home” and if this mirror is a home for you and a “hometown mirage” has no homes—what is the “steady mirror” that that you call “home?”

PC: Sometimes all you have is you. Sometimes you have to force yourself to love yourself. I learned from Don Mee Choi that the great poet Yi Sang used to carry around a mirror because he didn’t have other children to play with during childhood. It’s intriguing to think of a mirror as doll-like. As an imaginary friend. Knowing that makes many of Yi Sang’s poems even more intense for me. I have admittedly cried reading translations of his poems.

VKN: Also, what was your ideal comfort food that winters you through some social hardships? I am really drawn to rice even though there is a lot of arsenic in it. And, carbohydrates. Even though there is no winter in rice. Only summers and springs.

PC: Well, because you mentioned rice, I would be lying if I didn’t say sushi. But I wasn’t eating sushi in high school. Today, if I’m having a tough time, I’ll absolutely opt for sushi. It’s something I savor. I’m trying to think about the past though. A past comfort food. This might sound strange, but cereal. I would eat cereal throughout the day–as opposed to just breakfast. Honey Nut Cheerios. Golden Crisp. Mostly Golden Crisp.

KN: I used to do that too! Eat cereals throughout the day. They are like desserts ! Almond Honey Bunches of Oats. The sound they make when you crunch into them. Very satisfying.

PC: Yes. I agree.

VKN: Do you consume poetry like the way you do with cereal? So poetry is also your comfort food?

PC: Absolutely!

VKN: What is your favorite poem from this collection, Paul?

PC: I think that would be “Largo”–from the title section (“Fall Garment”).

Fall Garment is available from Schism Press as a $9 paperback or a free digital ebook

Vi Khi Nao is the author of six poetry collections: Fish Carcass (Black Sun Lit, 2022), A Bell Curve Is A Pregnant Straight Line (11:11 Press, 2021), Human Tetris (11:11 Press, 2019) Sheep Machine (Black Sun Lit, 2018), Umbilical Hospital (Press 1913, 2017), The Old Philosopher (winner of the Nightboat Prize for 2014), & of the short stories collection, A Brief Alphabet of Torture (winner of the 2016 FC2’s Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Prize), the novel, Fish in Exile (Coffee House Press, 2016). Her work includes poetry, fiction, film and cross-genre collaboration. Her first play, Waiting for God, is out of Apocalypse Party in January 2022. She was the Fall 2019 fellow at the Black Mountain Institute: https://www.vikhinao.com