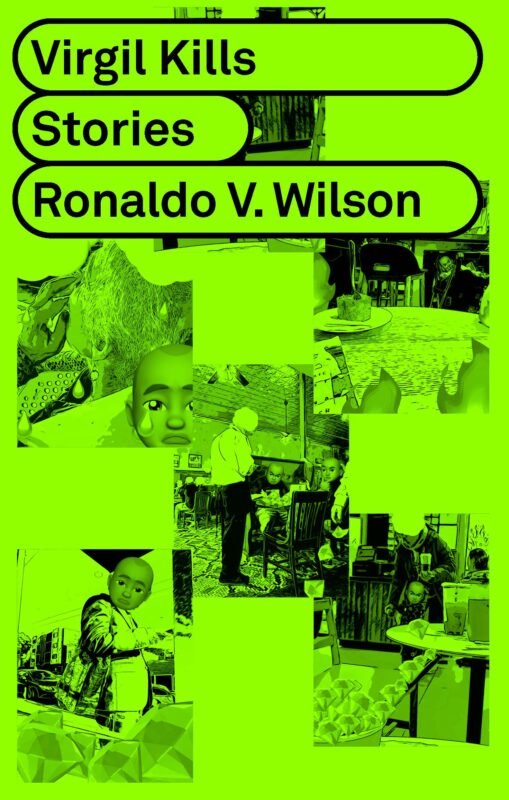

(Now available to pre-order from Nightboat Books)

The Platform

On the subway platform, Virgil shows off to the two blacks. One, he notices much more than the other, because that one is making a sound. This sound manIfests somewhere between beat box squeak and crow, or between a scream from a girl (or boy) being pounded out by a Chubold, or the actual Daddy Mugs—certainly into a boy—or the dryer which strains at an internal hinge, leaking its song, or the steel pulsing subway tracks, sound widening towards the waiting passengers.

The dream, itself, is suspended, so much so that he believes that Butch, upstairs, has died sometime in the night, or is actually dying at the moment Virgil hears these noises. But of course, Butch is alive, and the sound he makes in the night is not at all melodic, yet it’s something Virgil wants to hear.

What was that?

A bird crashing into the window.

Or maybe the sound is not a sound at all, but The Defeated’s mouth, which is like an octopus’ opening, the teeth separating. The jaws emit a beak, first, over Virgil’s eyes, jutting out to cover his face with its cutting. Virgil’s tongue is short and wide in his mouth.

Virgil’s teeth, though yellow, are symmetrical, and they keep him attuned to what he needs to make. When he tries to pull away, he is drawn back into the arms of The Defeated, dragging him from what he wants to be.

The puffy black bird—it snatches a blueberry from the bush and gorges it in the windowsill in Virgil’s vision, but the birdbath is empty. How does this absence attach itself to the fear he feels when he moves away from the blacks on the platform?

Nothing to stare at, no window, no anticipatory longing.

Virgil under attack by blacks is a racist constant—

“Let me see what you’re writing,” and Virgil, like a punk-azz bitch, says, “You mean my term paper?” and this relinquishment, forces him awake. In retrospect, Virgil cannot adequately reconstruct the dream, but he does recall the arrangement of power, a power over him, daring him to stand up from his desk by the boy, all black, while Virgil saw himself, as half, settled, even then, in the tension.

The encounter remains with him, but the dream, by the time he gets to its construction, is so far away; in fact, only the most racist remnants remain in his dream, the boy’s hair a minor fro, a muscle shirt, the ash on his jaw, his body thin, arm curvy and strong. Virgil’s body, flows, his hair, wet with Ultra Sheen, reading Tennis magazine, yellow Dee Cee’s with thin white piping down the side, all from Kmart, even then, Virgil was fattish.

It is less being between dream and memory that reveals the saliency of the experience, but something else, it’s what manifests between waking and carrying that drives Virgil’s critique. The morning (or post-nap) is the space where Virgil examines what just happened. The plot is pulling out of his own unconscious, and the plot is also pulling up something from a past he has tucked away. It is not accidental. It is, after all, a way of seeing into the questions of who that little brown boy was, and who this black man is, all in the space of saying:

I will not chase the consumptive.

I will, instead, involve myself in the productive. All against the threat of whiteness—

The sale on the Oliver Peoples frames. The artist who “redacts” language from the NYT—Blackness, or us, or all: In there, too, exists, plot.

Or the plot is in the fact that he cannot recall a single isolated idea, once it is written on the page. Perhaps it is the sea of argument he is after. CandidateOrangutan sports a red cap and wants to build a giant, beautiful wall between us and them, brown and white, and in the movie The Boy in the Striped Pajamas, there is a fence, and one boy (Bruno) goes under it, to look for his friend’s (Shmuel’s) father only to be caught up in a gang sweep and gassed to death.

He, the little white boy with brown hair and blue eyes is gassed along with him, the boy without hair and rotted out teeth. White/White. This happened, but bitch so did Slavery. So, the confusion is in the plot that divides the reality of what Virgil is into what he hopes to be, the submerged self, caught in the fantasy of becoming one wall, or the other—In other words, what sense might this scene make, and what’s the urgency of its return in the face of what Virgil chooses to watch, what’s real, and how might he sleep to disgorge these considerations?

Queen M says that the structure of the project that Virgil will carry as he moves across the fictive is bound by his dissertation, in what she names an “invisible scaffold,”—Virgil, attentive to dreams and memory, is also attuned to form. This is to say that he is interested in the ways that form works in collusion with vision, not content. Though this is crucial, Virgil knows that he’s liquid across such thoughts.

He understands this by way of walks—even in a Port Jefferson Station strip mall parking lot, he attempts to figure it out. This time, he is talking to Stream, who is

interviewing to elevate into another strata, from now being out of work, to the prospect of being in charge of directing cruises for the rich, those who can charter yachts to freedom, any single booking, a business expense.

Battle into whiteness, a city by the sea—

To work in prose, for Virgil, is not like working in collage, or in poetry. It is closer to being free. The freedom to pursue a line remains the source of the possible, to remain nimble in order to engage in the present, so any one encounter is only a set of coordinates as artificial relations between the subject and the scene, or the scene as the encounter becoming palpable within the scope of the dream—or chance—Virgil’s notations, life, etc.

By the gassing, Virgil is not devastated, but he wants amends, amends that cannot be made outside of what he renders or recalls. In the second part of the dream, Virgil looks at the unveiling of a boring party. There are Asians in that dream. The party, unveiled in stages, is a picture, opened up in sequences. The dream is staggered against this. A sequence is formed. Wind chimes, birds garble, and bark, too.

The Conversation

Some go on vacations to get away, but Virgil understands he must remain in one place even if Virgil goes. On vacation, Virgil likes to stay in the hotel, or he goes nowhere, or he goes back home to understand the limitations of who he is.

When Virgil returns to Sacra, to his childhood home, his father, Forgetting, To Live says, “You look just like Daddy….When you came into the house, you looked just like Daddy.” Virgil reasons it is only because of his baldness, but he realizes it is not only because of this, because Forgetting, To Live says, “Isn’t it funny how heredity works?” And he looks at Virgil closely to see something in his face, a long-remembered glance between a father and son from a past in which Virgil and Forgetting, To Live, connect.

On the other side of the green wall is a poster where DaddyJoliet is depicted running for an elected position. Virgil will read the poster, but before he does, he thinks Gubernatorial, a tangle in his head, and tongue, too, so he looks up the spelling before he writes it, but not after lifting himself out of bed into the home office to greet the old black and white poster that reads: Assistant Supervisor.

Knowing that DaddyJoliet was invested in a political life guides Virgil in the complexities of the conversation he has on the telephone with an editor. He tells the editor that he has written a play about his engagement with diaspora and mixed-race identity, things that Virgil negotiates, but are never spoken by MommaSpine, though Forgetting, To Live is the one that often recounts her past, in stories, to their children.

They hold memory, in secrets, in just out of sleep conversations behind their bedroom door, in the quiet early morning, and Virgil, as he can, listens and records. What to carry forward, and what slips out in the process? Virgil imagines himself a mobile site of identity, a wire trick in which he is: a gesture, a resin, through which to communicate, a way in—

Virgil: I see the rationale for the POV of the main character, from the buzz of the military biplane, and the water below its belly returning to the sea.

Editor: I don’t understand—it seems so abstract, though I suspect dense enough for unpacking.

Virgil: Look closely, you will see in me, a story of my mother’s fear, the fear in leaving behind who MommaSpine loves, her yellow family, for the black man she also loves, but the trouble is there is a radical fracture in this leaving, in the resultant family, a family with severed histories, a family heard in sing song voices submerged in a Skype call between CeSis, MommaSpine and those still alive. The main character cannot engage—right now—and so suspends in this refrain:

If they did not leave the Philippines, they’d be caught, and hung by their toes.

In the Skype call when MommaSpine returns from the hospital, she learns another brother has died. Her sister has died. She knows it. Her family has stolen, money, again, and things.

We wanted to send for them, to go to school, here.

Editor: But do you understand these parts? Are they retrievable? Do you understand how they may figure into a cohesive unit?

Virgil: Lots of questions, but I think so—Perhaps there’s a connection that has to do with me being the conduit for the very desire of their love, and its separation—to think through all the parts left in that Subic Bay Grey shot from inside the plane, out—this is the difference between memory and what’s on the Super 8 reels, what’s left behind “at the bottom of the sea,” as Forgetting, To Live sometimes says.

Editor: I don’t understand how it imports, but I do understand that it has to do with being mixed between incomplete, yet received and worn histories—this is something I do hear in your echoing so often, maybe even subliminally, the haunting phrase: WHO DOES HE THINK HE IS?

Virgil: Mixed is not like being a mix, like a mutt, but something else—It’s like struggling, or hanging on, or splitting yourself from the core of who you think you are and attempting to mine the vocabulary of the self, as in a café where I am marked as Brazilian, or when I say I am Filipino, marked, actually, as Black, which is, what I am, too. All of this is surface. Loss links, and so too, does violation, and of course, so does escape, and its cousin, exile.

Editor: I do understand some of these relationships to your vexed past, but what excites me is that there is, through it all, something that cannot be captured, yet still must be shown. I, too, am tired of the black and white dyad, and because I am tired of it, I move around wanting to know more about it! But my excitement, perhaps, I must submerge. But I might ask you to ponder the exilic.

Virgil: Yes, maybe, you’re right. The real engagement, after all, is a break from knowing. When I was watching myself online, I looked very fat until I saw myself move back from the lectern, looking into the sky, into the light, into the knowing of who I wanted to be. There my face was thin, so isn’t this the point, too? When I don’t eat, shadows.

Editor: I see what you mean, for sure, and I will consider this, but do remember I am taken, mostly by your ability to listen, and who you are on the other side of the phone, what you may be, and how you might help us to see you.

Virgil understands the source of his body as fact, as a point of realization, the connections less between each story than their being wed to a path that marks the past, circling around the desire to know, and to understand what can’t be connected. Virgil’s interpretation punctuates his desire for feeling, for an understanding of his own body, less grounded, but turning, into an inside, nonetheless, he makes.