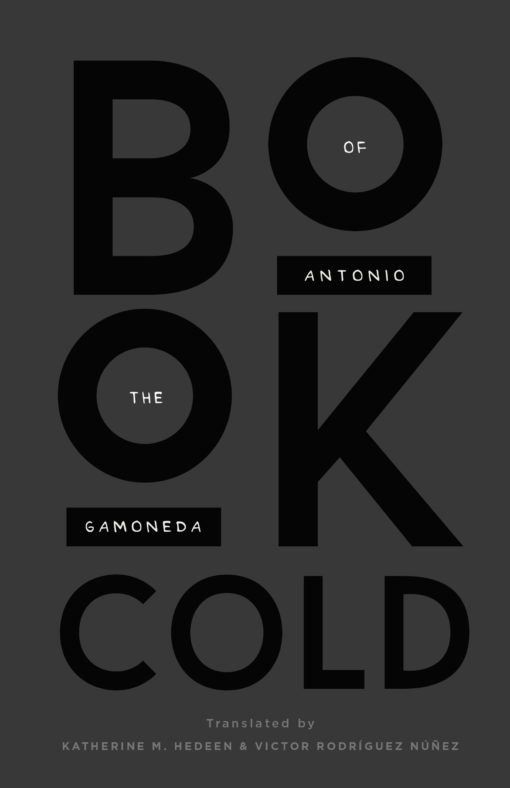

In Book of the Cold, memory burns up like flowers; vertigo stills a reader’s perception as much as it dizzies; and sight-blurring rainfall rages like a sculptor’s hands. Brilliantly translated by Katherine M. Hedeen and Víctor Rodríguez Núñez, Antonio Gamoneda’s Book of the Cold is a breathtaking exercise in synesthesia (“I smell the linseed and shadow”); verbal intensities (“Before the winterscorched vineyards I think of fear and light”); and ecological phantasmagoria (“All the trees have begun to howl within my mind as they / remember your underclothes in the darkness, the light under / your skin, your living petals.”). Fans of Aase Berg’s heavy scenes of clay (“We galloped across the field this empty day as it rained clay and lead and the snow lay half-melted here and there in the flaccid landscape”) and Paul Celan’s compressed yet plentiful lines (“Silence! The thorn drives deeper into your heart: / it is in league with the rose”), will surely appreciate this poet’s radical reconfiguration of nature:

Is the light this substance that birds move through?

In the silica tremor quartz and thorns settle smoothed by the

vertigo. You sensethe seahowl. Later

cold of limits.

What exactly might Gamoneda mean by the “cold of limits”? According to the translators’ note, after the Spanish Civil War, Gamoneda was “fiercely opposed” to Francisco Franco’s dictatorship and joined a resistance movement in response. It’s no shock that critics haven’t since classified Gamoneda as a poet of the “establishment”. Hedeen and Rodríguez Núñez note:

There, in the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War, [Gamoneda] witnessed firsthand the repression brought about by the dictatorship of Francisco Franco, in power from 1939 to 1975. He taught himself to read with his father’s poetry and abandoned his schooling completely by age 14, taking a job as a messenger at a bank to help the family.

Perhaps this is why Gamoneda’s poetry feels so limitless, especially in learning that he used his father’s poetry (who actually shares his name) to teach himself how to read. Knowing this, an aesthetic limitlessness (or poetics of excess) might be an attempt to move beyond this metaphorical cold—beyond “abyss”:

I am cold beside the springs. Climbed until my heart was weary.

Black grass on the hillsides and violet lilies in the shadows, and

still, what am I doing facing the abyss?

To lock oneself in Gamoneda’s whitening “prison of cold” is to question that which seems abysmal. To see a darkness in light. To see and be split by a language of corrosive images. Like caustic soda (also known as “lye”), his poems depend on absorptive images and a white deathly atmosphere. White kitchens, white grass. At different times, the color white appears to evoke the “sweetness” of sugar or blood or sex.

Someone has moved into the white memory, into the heart stillness.

I see a light beneath the mist and the sweetness of error makes me close my eyes.

Book of the Cold feels like a relentless search for purity. The sickening sweetness of a memory. A loved one’s suicide. A mother’s touch. Early in the collection, the speaker associates a “softness” or “sweetness” with notions of mother. Later, a mother’s flower-like “armpit”. As each poem unfolds, the purity of memory feels like both lye and lie. A purity that increasingly resembles poison and remedy: pharmakon. Memories like sugarcubes. A sublime sweetness.

Slajov Žižek has likened Plato’s pharmakon to a shadowy double, a form of madness. Coincidentally, drunkenness and shadows also frequently haunt Gamoneda’s poetic sequences:

You hear the wood destruction (the blind termites in its veins),

see the needles and wardrobes filled with shadow.It is the mortal nap. So much childhood beneath the eyelids!

Like with the sad horsefly in summer, you brush your mother’s

black serge from your face. Youwill awake in oblivion.

Fatal if swallowed, but also used in the production of soap, Gamoneda’s lyes and lines blend with the natural world, forming steel-cold songs of darkness and light:

Birds. Moving through rains and countries by the fault of magnet

and wind, birds flying amid the ire and light.Sibylline they return under the laws of vertigo and oblivion.

What is cold? What is purity? What is light? What is love? Gamoneda’s Book of the Cold asks complex questions and much of the collection feels like a poet’s desperation to move beyond the shadowy, existential coordinates of existence. Move beyond limits! Yet—memories swell like creeping fungal blooms. Rich in natural imagery, one cannot shake the notion of a mother earth turned tragedy. A “carbide sadness”. A song of ceaseless “birdflow” and “ire”:

Nothing is quick in your memory except the eyes of the suicide,

the one who set trees to fire with hands expert in poverty and ire;nothing is true and the omens hopelessly moving through your

ears, oh wretched one before the snow.

To enter the Book of the Cold is to enter the wound of an ultimate poetry.

Paul Cunningham is the author of Fall Garment (Schism Press, 2022) and the The House of the Tree of Sores (Schism Press, 2020). His latest chapbook is The Inmost (Carrion Bloom Books, 2020). He is the translator of Helena Österlund’s Words (OOMPH! Press, 2019) and two chapbooks by Sara Tuss Efrik: Automanias Selected Poems (Goodmorning Menagerie, 2016) and The Night’s Belly (Toad Press, 2016). He holds a M.F.A. in Creative Writing from the University of Notre Dame and a PhD from the University of Georgia. He co-manages Action Books.