To further support Action Books’ growing community of writers and readers, we’ve decided to launch a new initiative on the Action Books Blog. Selected by our editorial staff, a recurring series called Action Fokus will highlight excerpts from 12+ radical manuscripts submitted by poets and translators during our 2022 Open Reading Period. Today we are featuring excerpts from Eric Wayne Dickey’s translation of Arnfrid Astel’s Iamb(s) and Butterfly(lies) or Amour & Psyche: A Butterfly Study.

The narrative arc of this book journals Astel’s coming to terms with the loss of his son to suicide. Astel’s poetics deliver in ways that will add to American poetry sensibilities. It is of no single “school” of poetry. While it incorporates science and biology, travel and place, it seeks to document the personal growth and transformation with processing grief. The book is meditative and stream-of-consciousness-like, using free and blank verse, haiku, iambic pentameter, and the German alexandrine. It is hypnotic in its repetition and cadence, and we easily lose our minds, as Astel must have, navigating the emotional abyss created by his son’s suicide.

It is difficult for me to characterize this book. Since it includes Latinate and common names of plant and animal species, it reads like a scientist’s field notebook. It also reads like a travel log. On one hand it is a book of short poems, on the other it can be read as one long poem. Divided into six parts, each part is composed of shorter poems, and each part can be read as a poem itself. In that sense, it is fractal and looks at the very small to see the very large. The six sections are followed by a playful epilogue. Each section brings the reader closer to Astel’s own grief. The book starts in denial, writhing in the mud with mussels and snails. Section two takes a close look at butterflies and discovers a path to acceptance. Sections three and four are the physical and mental journey to a place of healing and are a “Joseph Conrad/Heart of Darkness” exploration: The book was published during the Bosnian War, and the fourth section documents a trip to the Dalmatian coast: The metaphor is a retrieval quest, where the poet describes the landscape beauty in the middle of turmoil. Section five is filled with recovered memories of happier times. And section six is the actual coming to terms with the loss. For Astel, the butterfly represents Iambe, the aged maid who helped Demeter forget the loss of her daughter Persephone.

The book will appeal to poetry writers and translators, to scientists of biological oceanography and of entomology, to travelers in Europe, to students and teachers of language and language arts, and, on a very personal level, to readers dealing with loss. The translation manuscript went through eight or more drafts and has incorporated the criticisms and suggestions from over a dozen people, poets and translators and a university professor of German. It is a very precise translation that captures Astel’s poetics and the poetics of the German language in ways that will challenge and appeal to readers.

—Eric Wayne Dickey

from “Dalmatian Journey III”

Like a HEDGEhog against the sun.

The pine trees prick the light.

A snippet of Apollo:

the resin drops

on the pinecone.

A flash of light

hits me in the shade,

brilliant and exact.

PINEAPPLES

Pineapple,

the pinecone,

of the ananas.

The hand grenade

feels heavy

in my hand.

The cone

on the grave fence

is of cast iron.

The corner posts

are thyrsus staves.

BUDVA

Over the graves,

the tree.

Oranges in the grass

are to bite into.

THE grasshopper

the winged horse.

PEGASUS, Priapus,

grasshopper,

my hobbyhorse.

THE mussel,

my snailhorse.

THE seahorse,

the dragon of Supetar.

IN THE PINE SHADOWS

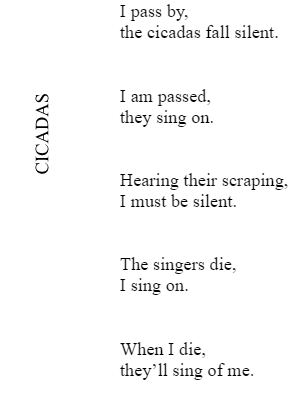

When the cicada sings,

the cones open their lips.

OMEGA

is the sign of

the injured cicada.

It writhes in its final

throes in my hand.

THE dying tettix

carried to Mithras,

through the grotto in Močići,

to the cicadas.

IN the glass coffin,

the immortal cicada.

Does the cicada

CARVE its name

in stone?

SCRAPE, cicada,

the longer, the lovelier,

you move me.

On the epitaph

in my book,

lies the cicada.

You CAN hear

them with your ear.

But to find

them on the rind,

your sight

must

be right

AROUND here,

cicadas sing

of the island.

CICADAS sing of

the island of the dead.

IN the beginning

was the tree

and the branch.

Then came

the ship

and the mast.

In the end

the wreck

and the A.

So it stAnds

there.

WHEN I am dead

you will get a bone.

You can cook for yourself

a little soup

from those holy relics.

When I am dead,

you will get a bone.

Hans Arnfrid Astel (1933-2018) lived and worked in the Saarland region of Germany. He spent his childhood in Weimar. In Heidelberg 1959, he founded the poetry journal, Lyrischen Hefte, which appeared until the ‘70s. In the ‘60s, he wrote literary criticism for the Neuen Deutschen Hefte for Joachim Günther in West Berlin. From 1967 to 1998, he led the Literature Office at the Saarland Broadcasting Company in Saarbrücken, for which he produced readings and comprehensive interviews with authors. He had his finger on the pulse of German poetry. During the mid-1980s, Astel’s writings changed from political poetry to nature poetry.

Although very little is known of Astel outside of Germany, his legacy is important to German poetry as is evidenced by a book that was released for him in 2003, a book with contributions by friends and colleagues: Seit Ein Gespräch Wir Sind (Since a Conversation We Are: Arnfrid Astel on his 70th birthday: Texts for him, about him and from him, ISBN 3-935731-53-1).

Astel received the Gustav Regler prize in 2011. His poems have been translated into Hungarian, Italian, and French, and a few into English. Information on Astel is located at www.zikaden.de, on which you can find his poems and lists of his publications and awards. From a political poet to a poet recognized far and wide, Astel increasingly set his sights on the possibilities in electronic publishing and produced several works and collaborations in the last years of his life.

Eric Wayne Dickey holds a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing and an Honor’s BA in English and Philosophy from Oregon State University. He is a John Anson Kittredge Fund for Individual Artists grant recipient administered by Harvard University, and a Vermont Studio Center Fellow. He has received fellowships for publishers from Oregon Literary Arts in 2005, 2008, and 2018 for Pacifica: Poetry International, an international poetry translation journal. He has published two ebooks of original poetry: The Hardy Boy Poems (Beard of Bees, Chicago: 2013) and Forgive Me, Tiny Robots (Argotist Online, UK: 2013), and a children’s book, Alex the Ant Goes to the Beach (Craigmore Creations, 2014). He has poems and translations in PageBoy, Cloudbank, Lummox, and Rhino among other journals. Online, you can find his work at Blazevox, Talking Writing, Truck, and On Barcelona, and at Contrary Magazine which nominated his poem “James Dean” for a 2020 Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net. Erica Goss interviewed him about his manuscript The Book of James for her newsletter, Sticks and Stones, (January 2021). He received an honorable mention in the 2021 Angela Consolo Mankiewicz Poetry Prize contest by Lummox Press for three poems from The Book of James.