[The Action Books Editors and Advisory Editors share their favorite books of poetry in translation published in 2022.]

Nicole Cecilia Delgado, adjacent islands, translated by Urayoán Noel, Ugly Duckling Presse, 2022.

In this bilingual edition, Nicole Delgado’s vivid poetry and Urayoán Noel’s deft translations transport us to Mona and Vieques in the Puerto Rican archipelago. Throughout, we witness the poet and her companions camp in these tropical spaces. While they sleep outside, swim naked, pick fruit, and watch the rising sun, they also confront the environmental wounds wrought by colonial militarism. Delgado’s words render their spiritual communion with islands as her community formed new kinships, saw the open sky and its constellations, and listened to the profound songs at the bottom of the sea.

— Craig Santos Perez

Lara Dopazo Ruibal, Claus and the Scorpion, translated by Laura Cesarco Eglin, co•im•press, 2022.

In claus and the scorpion, Lara Dopazo Ruibal’s Galician and Laura Cesarco Eglin’s English reach for each other with the fitful intimacy of siblings or lovers locked forever in ballistic proximity. Here is a poem of the just-detonated world in which we all find ourselves suspended, also known as the present tense: songlike and shattered, permanent and elapsing, ultra-compressed and expanding at both snail-like, cosmic speeds as it achieves its ideal form—divine “smithereens.”

— Joyelle McSweeney

Dolores Dorantes, Copy, translated by Robin Myers, Wave Books, 2022.

Dorantes certainly pushed boundaries in her journalism, and she does so in her new book. Though it rightly bears the words “translated by Robin Myers” on the cover and title page, Copy is, in the fullest sense, a collaboration. Between the covers, the two poets together explore profound questions of identity, which play out in the act of copying themselves, always with the proviso “copiously.”

— Paul Vangelisti, LARB

Antonio Gamoneda, Book of the Cold, translated by Katherine M. Hedeen and Víctor Rodríguez Núñez, World Poetry Books, 2022.

Gamoneda’s Book of the Cold asks complex questions and much of the collection feels like a poet’s desperation to move beyond the shadowy, existential coordinates of existence. Move beyond limits! Yet—memories swell like creeping fungal blooms. Rich in natural imagery, one cannot shake the notion of a mother earth turned tragedy. A “carbide sadness”. A song of ceaseless “birdflow” and “ire.” […] To enter the Book of the Cold is to enter the wound of an ultimate poetry.

— Paul Cunningham

Raúl Gómez Jattin, Almost Obscene, translated by Katherine M. Hedeen and Olivia Lott, Cleveland State University Poetry Center, 2022.

You could not simply peer down from above, nor would you want to—to enter Raúl Gómez Jattin’s image world is to be on earth with your own bursting, breaking heart. Through this act of translation by Katherine M. Hedeen and Olivia Lott, new readers can encounter not only “loneliness and its causes,” no, not only verses of exhaustion and devastation, but also, somehow, a “whole wonderful life.” How sweet the sound. Almost Obscene assembles a queer companionship of rag doll children, papier-mâché lovers, the Sinú River, and most of all poetry itself, a “dangerous ceremony” Gómez Jattin chose to attend. I cannot wait to return over and over again to this open field, noisy with sorrow and joy, under constellations shaped by his divergent lines. “Poetry and love did this to me,” he writes, and poetry and love could do this to you, too, if you let them. Part manifesto, part self-portrait, this is a book of amazing grace in a maddening world. Gómez Jattin’s poems from the margins shift the very center. I am sheltered in the body of this work.

— Oliver Baez Bendorf

Maricela Guerrero, The Dream of Every Cell, translated by Robin Myers, Cardboard House Press, 2022.

Encouragement is a round warm form of resistance,” writes Maricela Guerrero, as if describing her own project. In these powerful and necessary poems, beautifully rendered by Robin Myers, Guerrero reveals a worldwide cellular consciousness that generously offers us rivers of leaves and wolves to feed and clean the heart and its languages. Building furrows of words and speaking in tree, Guerrero creates a poetry to shelter in. In her capable hands and tongue we are carried in rivers of nourishment. It’s exactly what the world needs, and I am flooded with gratitude. For joy, for grace, for tenderness, for righteous grief and its acknowledgment, for inspiration and sustenance, you must read this book.

— Eleni Sikelianos

Rodolfo Hinostroza, Contra Natura, translated by Anthony Seidman, Cardboard House Press, 2022.

The work of Rodolfo Hinostroza carries us into a world of physical & spiritual poetry at its limits & beyond: a further gift from the Southern continent in line with the likes of Vallejo, Huidobro & Neruda, & no less powerful for all its late emergence. For those of us who want & need the fullness of a poetry unfettered, Contra Natura takes its place as one of our new essentials—a ripeness & overabundance for which I’m truly grateful.

— Jerome Rothenberg

Paula Ilabaca Núñez, The Loose Pearl, translated by Daniel Borzutzky, co•im•press, 2022.

Paula Ilabaca Núñez’s The Loose Pearl is an intense, bawdy, bodily fairytale about sexuality, and it is an “eruption” of poetry. It’s the kind of eruption that takes place in writing when you move beyond expectations and conventions and good taste into a realm where anything can come into play as long as the poet has the skills and daring to make it so. In The Loose Pearl, fucking is fucking (it has to be, it’s how the text writes the body), but it is also the act of engaging in and attending to this act or moment of eruption. This is the most important truth about writing. This is both the first lesson and the last lesson of how to write poetry.

— Johannes Göransson

Hiromi Itō, The Thorn Puller, translated by Jeffrey Angles, Stone Bridge Press, 2022.

The sparks of humor fly as Japanese medieval narrative and Judeo-Christian culture collide in modern-day domestic disputes. Ito may have written this book in prose, but we never forget that she’s a poet. There is a special music even in the complaints, scolding, arguments, phone conversations, and gossipy moments. As the narrative unfolds, Ito draws not only upon voices of her family members and others around her, she gathers in countless voices, including those of the dead. And how wonderful to find the rhythm of the Japanese reproduced so marvelously in this translation!

— Yoko Tawada

Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine, I Caustic, translated by Jake Syersak, Litmus Press, 2022.

Khaïr-Eddine’s excoriating satire of independent Morocco, written in the first decade of Hassan II’s rule, from the remove of voluntary exile in France, performs a devastating critique of the violence of the ruling class, the incompetence of government, the hypocrisy of organized religion, and the stubborn presence of police brutality, even as it fashions radically new modes of literary and poetic expression. Sometimes crude, even grotesque, often brilliantly seductive, irreligious, and funny, Jake Syersak’s bold translation into English breathes new life into this important and too-long neglected work of modern Moroccan literature.

— Thomas C. Connolly

Shuri Kido, Names and Rivers, translated by Tomoyuki Endo and Forrest Gander, Copper Canyon, 2022.

Shuri Kido, known as the “far north poet,” is one of the most influential contemporary poets in Japan. Names and Rivers brings the poems of Shuri Kido to readers in North America for the first time, thanks to star translator team Tomoyuki Endo and Pulitzer Prize winner Forrest Gander. Drawing influence from Japanese culture and geography, Buddhist teachings, and modernist poets, Kido presents a mesmerizing view of the world and our human position in it. This is a world “that isn’t ours”—where the trees are sirens while the people are silent, where snow lingers while language crumbles. Names and Rivers is made of crossings, questionings, and mysteries as unanswered and open as the sky. Bilingual Japanese-English production.

Kim Hyun, Glory Hole, translated by Sunyun J. Ahn and Archana Madhavan, Seagull Books, 2022.

Kim Hyun’s Glory Hole is the first Korean queer poetry collection. Featuring gay teens, elders, cats, caterpillars, robots, and other unexpected characters, Kim’s fifty-one eccentric poems trace themes of love, sexual desire, abandonment, destitution, and death. In recounting the splendid yet tragic journeys of his speakers, Kim defies meaningful sense-making. His poems are a mishmash of dystopian sci-fi and pornography, storytelling and poetry, fictive references, and real figures. They are not embellished with elegant imagery; in fact, they are antithetical to it, opting instead for incoherent tense, unidiomatic expressions, and never-ending puns. After all, like LGBTQ+ people in many cultures, Korean queers live in this site of violence. Bewilderment, deliberately, is Kim Hyun’s form. Glory Hole invites readers into a very queer world.

Hugo Manríquez García, Commonplace, translated by NAFTA, Cardboard House Press, 2022.

These poems both catalog and interrupt contact between the military and the ecological in everyday contexts: how traces left by the glands of a white-tailed deer and petals from bright yellow creosote also touch Colts and Glocks and ion scanners. In doing so, they ask me to confront whether there remains anything private in my so-called private life. As García Manríquez writes, “When we read literature / we read the budget of the Mexican army.” And in that budget, we may spy the poetics of our own elegies. This compact, but frightening, book invites us to consider “The collapse of abstraction / as another form of freedom.”

― Divya Victor

In the Same Light: 200 Poems for Our Century from the Migrants & Exiles of the Tang Dynasty, translated by Wong May, The Song Cave, 2022.

Chinese poetry is unique in world literature in that it was written for the best part of 3,000 years by exiles and refugees. In this anthology, we meet Du Fu, Li Bai, Wang Wei, and others less familiar to readers in English. Known as the Golden Age of Poetry, the Tang Dynasty was a time when poems were bartered for wine and tea, posted in temples and taverns; the words of poets unmissable as street art and signage. Monks, courtiers, courtesans, woodsmen, and farmhands alike were all fluent in poetry. More than reading matter, it was a common currency—whether as a necessity or luxury in times of rampant warfare, droughts, famine, plague, man-made and natural disasters. Chinese history can be read in the words of the poets. It was left for poetry to teach the least and the most, says the translator; literacy of the heart in a barbarous world. True to the spirit of classics, these poems from 1,200 years ago read like they were still being written somewhere in the world — to be read today and tomorrow: “In dark times we read by the light of letters.”

Ennio Moltedo, Night, translated by Marguerite Feitlowitz, World Poetry Books, 2022.

Ennio Moltedo, translated now for the first time by the daring mind of Marguerite Feitlowitz, conveys the Chilean night in all its linguistic, political, and cultural meanings: darkness, affliction, and absence of ethics or reason: the enduring wounds of Chile’s dictatorship. In this quest for clarity amid darkness, Moltedo’s poems reverberate with the force of a language writing its way out of the psychological shackles of the state.―Daniel Borzutzky

Vivek Narayanan, After, NYRB Poets, 2022.

Wildly ambitious book . . . After is a grand literary experiment . . . Across 600-plus challenging and deeply rewarding pages, Narayanan teases out subcutaneous layers of meaning, psychological depth and cultural commentary from Valmiki’s epic.

— Aditya Mani Jha

María Negroni, Exilium, translated by Michelle Gil-Montero, Ugly Duckling Presse, 2022.

María Negroni writes like a dancer working the barre, her movements lovely, stark, and essential. Her discipline points toward methods of survival despite the body’s disquiet, despite “wrongful objects / in the kiosk of the sky.” Michelle Gil-Montero’s rendition in English conveys the energies and austerities of each poem extending down the center of these pages: toned, gauzy, marvelously nocturnal.

— Kristin Dykstra

Ursula Andkær Olsen, My Jewel Box, translated by Katrine Øgaard Jensen, Action Books, 2022.

It’s beautiful and desirable; it’s nonporous (i.e., it can no longer be entered and no longer extrudes material) and inscrutable in its smoothness; it’s distinct from humanity and humanity’s feelings and attachments. And, most importantly, once it’s been cleaved from the self, the orb can be put on a vessel and sent away. In the universe of the main narrative of Outgoing Vessel, humanity is unrelatable; comfort is unrelatable; healing and journeys are unrelatable; the only aspirational thing is hardness as a new efficiency.

— Niina Polari

Liliana Ponce, Fudekara, translated by Michael Martin Shea, Cardboard House Press, 2022.

The work’s evanescence, its ‘not being,’ the composition of the void, of the space between the lines, is the art, the mastery of Liliana Ponce in Fudekara, to make present what is felt, the other reality within ‘reality,’ released by and through the brush.

Her admirable reticence is a bolt of world-opening lightning.

— Cecilia Vicuña

Sotero Rivera Avilés, The Rust of History, translated by Raquel Salas Rivera, Circumference Books, 2022.

If you could take off your arm, give it to your grandchild to play with, would its hand be open or clenched? “Te sería muy fácil seguir viviendo,” the poet writes, which the grandchild translates as “To go on living will come easy.” Poets sometimes make a great deal of the power of the particular, and that’s not wrong. But it’s also right, for this book, for this translation, to sometimes drop a singular reflexive pronoun like “te” and hand over a verse, specially one with the promise of access to life, to all of us. Yes, the poet is keenly aware that the biological arm was taken by imperial war, that colonial poverty sentenced him to years in diaspora, that colonial poverty was there to welcome him back. But the poems of Rivera Avilés—in their original forms as much as in Salas Rivera’s translations—know what Audre Lorde knew in “The Uses of the Erotic”—that we can continually handle and hand over the particulars of the everyday as portals to a life force that is a collective birthright: all earth without a nation state, all love without fear, all freedom without selfishness, all joy without shame.

— Farid Matuk

Víctor Rodríguez Núñez, midnight minutes, translated by Katherine M. Hedeen, Carrion Bloom Books, 2022.

Víctor Rodríguez Núñez’s poetry represents a profound renewal of poetic language. It forces us to see that poetry accounts for itself precisely because it accounts for the world

— Raúl Zurita

Peter Weiss, The Shadow of the Coachman’s Body, translated by Rosmarie Waldrop, New Directions, 2022.

Exhilaratingly strange, compelling, and original.

— Bookforum (RIP)

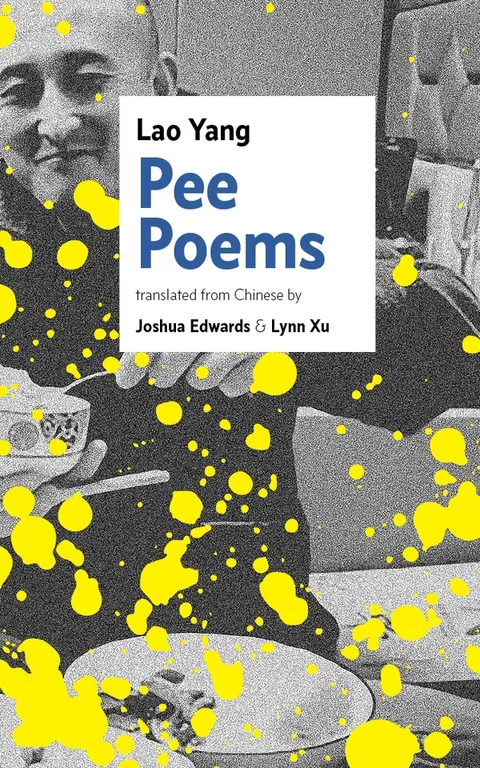

Lao Yang, Pee Poems, translated by Joshua Edwards and Lynn Xu, Circumference Books, 2022.

In his provocatively—yet delightfully—titled collection Pee Poems, Lao Yang hurls his poetics outright. “Don’t call me a poet,” he writes, “call me a piss person. Like a ‘juicy meatball,’ bursting suddenly in the mouth and spilling out: piss person” (emphasis in original). Anthropologist Mary Douglas’ seminal formulation of dirt as ‘matter out of place’ feels appropriate here, for Yang’s self-disclosure as a piss person challenges the perverse abjection of our bodily expulsions. Sure, urination is a natural function, despite the fact we displace its processes from public view, but as Yang notes, it is also a political act. Indeed, Yang’s status as a piss person not only underscores the socio-political conditions attached to the body’s excesses, but urination is also an extension of a wider political ecology, where ideas of freedom and autonomy are often contested subjects. “When even the right to cry is denied,” he writes, “Incontinence is one of the few remaining liberties.” Far from being matter of place, Yang insists on staging the politics of waste in full view to disrupt the boundaries between the body and the body politic. Case in point is the following poem, where the anaphora accumulates a steady stream of political barbarities and contaminations

— Orchid Tierney

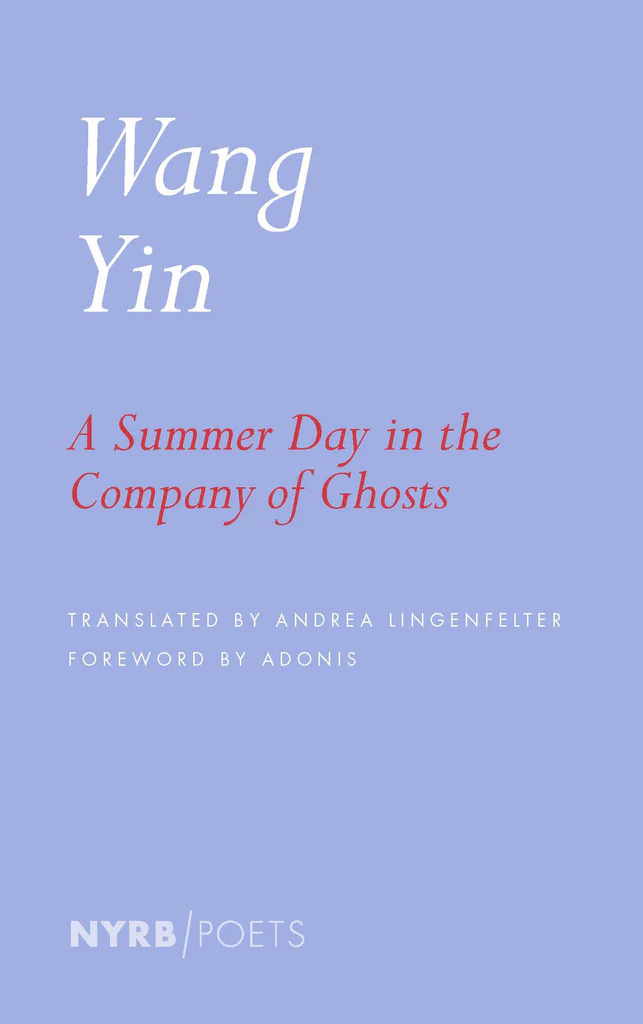

Wang Yin, A Summer Day in the Company of Ghosts, translated by Andrea Lingenfelter, NYRB Poets, 2022.

The poignant clarity of Wang Yin’s images, so memorably rendered by Andrea Lingenfelter, makes his poems burn in your brain long after you close the book.

— Forrest Gander