To further support Action Books’ growing community of writers and readers, we’ve decided to launch a new initiative on the Action Books Blog. Selected by our editorial staff, a recurring series called Action Fokus will highlight excerpts from 12+ radical manuscripts submitted by poets and translators during our 2022 Open Reading Period. Today we are featuring excerpts from Lucía Boscà‘s Aphasias translated by Karen Elizabeth Bishop.

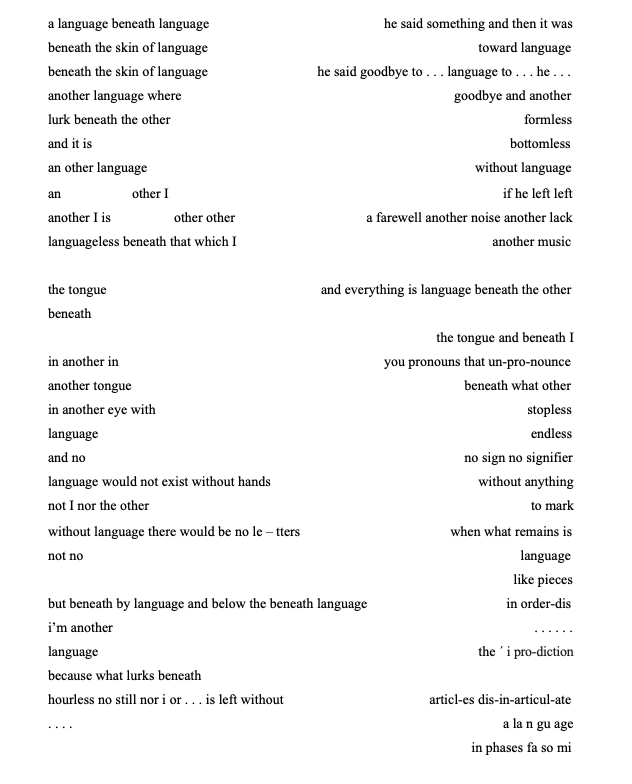

In her 2019 book of poems, Aphasias, Spanish poet Lucía Boscà gives us a broken language to interpret a broken body and a broken world. Here aphasia—loss of speech, an inability to make or understand language, the bodily breaking down of communication—becomes a way to describe and intervene in a world that has become itself unspeakable. In this sense, aphasia speaks the world more authentically than any stable speech might. It speaks in starts and stops, caesuras, blind spots, misidentifications, metonymies, layers, holes, gaps, and minor lucidities that shine too brightly in an otherwise dark field. But for Boscà, these are not anomalies of language or errors; they are rather fundaments of speech so that speaking whole, non-aphasiac speech, becomes the strangeness, the impossibility in a world itself always coming apart. She calls out, she challenges, the comfort of whole sentences, sense-making syntax, and nouns that too aptly apply to reveal the pauses, stuttering, inferences, slant rhymes and pitfalls that populate the constitutive, world-making rupture that language covers over and up for. The poetics that emerges is both riot and return, revolution and homecoming.

Translating Boscà is to enter into a profoundly destabilizing landscape of sound, image, and radical new combinations of object, self, memory, time, and dwelling. Like a scar that offers new flesh, her language gives the translator new material to work with. I have made up words, split images, reorganized syllables, dug up affinities, lost the thread, and taken refuge in sound. To translate speechlessness demands a remaking of language from the ground up so that the new words, sounds, syntax, and order that the English-language version takes on offers to readers a new language to inhabit, and with it new forms of world- and self-inhabitation. These forms of, in Boscà’s words, “illness or dwellable onlyness” recast the relationship between body and brain, limb and mind, object and intention. An unstable, often newly violent world that cannot be relied upon finds its match in a fragmented, halted, and overwhelmingly beautiful language that reapportions protagonism to a broken, worn body that navigates our modern world. Aphasias is a radical, necessary work of off-lyric that brings into English one of today’s foremost experimental Spanish poets.

Dog is dog.

I told you not to eat

the sun. Or I’ll

come after you with an

iron rod.

Eat the sun then. In the

whole brain.

It was so in-

side him, deepereventhan

the rod of.

So muchwater and a violent

conflagration

velo city

is Factor V Leiden,

intracranial clots,

pou n ding clots

come pounding and to o-

ur dead who are here and

—can’t you hear me?—

who write “past tense corpse,”

who move the white cat

on its little feathered pillows on my

pal pitating lids

pa rents that refuse to be so:

fear is this neglect,

the asphyxia of the umbilical cord

that nourished him all those months,

that new li shed him all those months.

Nothing d doesn’t wor kfforus nn oteven

co ming a p art

i look for you every . . . every once

in a while in between on

the bench all in white an il legible message

no on in come back come (a plea: back!)

like ha dhark sparrow ohr any hanimal

like the cat that also white of his eyes on the asphalt

and no, not even with so many nos to hold them in place

nnn ooo come back and every morning the girl emerges from the den and

the air encloses her body fragile naked in the early morning fog

the girl looks through the clouds that were always

only sound and it’s you moving around between the sheets, thousands of miles a-

way with i don’t know who, memoryless, a diving bell, with ouht a sing le be

at w i t h o uht a pumpum pumpum surfaces looks for its name, your name,

calls it out and no nothing comes back

nothing will do anymore nothing when no not an all no not a nothing no

no when no

wind is left, flesh, eyes with which to live.

Syntax. Scalable dark.

(Be)low ( ) the etymology: before — after.

Destruction by technification. Write without verb.

Smoke takes on the air.

Stains like doubt.

Möwe: graphic gulls: « »

But the rock pregnant with death

—more treacherous than a termite’s nest—

orb, bores through the glass of your retina

without breaking it, like a sun

of poison yolk.

Man stores within the hollow of his eye the bile of the snow owl

so he can see through his neglect and translate without choosing:

“make tremble the

word, see-it red,

invent

dialects: a syn

denton, arctic poppy, arc- op- ama-ryllis, tra, la, la, tra, tr-auma, tr

achea, traum (wound, dream)-a.”

In the incisor’s cavity lives the man who watches, the maxillary

man ground up aswellaswell, so good…the ground down maximary man

man lives, yes, he also lives***

***his own disappearance.

If our history doesn’t erase what it hides,

why does illness or the dwellable onlyness unleash a bolt in the

brain that descends down to the neck, making, unmaking the liquid, your

inward gaze, phonemes in the dark,

why, why in the night the scent of roots when it’s not here any

more it comes looking for me

and fear it does not find, nor my sick neck of

suspicion,

but a body thirsty for dirt to nourish my center of featherless bird

lost in the forest,

why do only you get up close to it, break through the branches

and the forbidden,

concede the speech, decipher life’s rash of discomfort,

why only you when you it comes from strange bodies, on

a performative history, made of its own enunciation

– i swear to you, i swear to you,

i ma mmmma k eyou, i unmake you am am ong stoma open to

de pth st oma so und y our skin in inbetween, the dwellable onlyness –

why, why does the dwellable onlyness not fit in a pronoun,

the dwellable onlyness . . . is the speech-act, the impossible?

My body has lived

death. In death are

unpronounceable languages.

Straight scatter when

the dead speak to me.

The voiceless light

tells nothing, waves that don’t blossom

that say nothing because they

have nothing to say

and even so they say “come” and “return”

and i go down again,

beneath the skin and finally,

to be able to, at last, i can (,)

to be able to and birth and say what do they say they say:

“What of desire in fear?”

And without fear there’s no

body, pronounciation and what’s missing.

Lucía Boscà is a poet and professor from Valencia, Spain. Aphasias was published by Kokoro Libros in 2019. Boscà’s 2014 collection Ruidos won Spain’s prestigious Premio Poesía Joven Félix Grande, and was published by Colección Literaria Universidad Popular. Her poems and essays have appeared in numerous Spanish-language journals and anthologies in Spain and Latin America. She is widely considered to be one of Spain’s foremost experimental poets.