curated by Katherine M. Hedeen

Reviewing poetry in translation

- recognizes translators as authors

- destabilizes narrow definitions of originality, authenticity, and authorship

- makes visible the artistry of translation

- is dissent, defiance, disobedience, subversion, solidarity

Where better than the Action Books blog to do the work?

Microreviews of poetry in translation coming at you every few months right here!

Claudina Domingo.

Claudina Domingo.

Impossible Hours.

Trans. by Ryan Greene.

death of workers whilst building skyscrapers, 2022.

41 pages.

£19.66.

At first glance one might see the sprawling disjointed text of Impossible Hours as frenetic—a clamor for the blueprints of a lost city. But Claudina Domingo’s archeological and architectural poetics are a comprehensive and reflective tribute that invite meditation between the past and present. Mexico City has been remarkably broken open by forces of nature, colonialism, and politics, and put back together again many times over. As in any city where life must go on, the risk of collective memory loss and repetitions of history are most apparent to the ones who refuse to look away. In this collection, Domingo marks the past’s every fissure and echo through critical observation that resists clarity as it commands witness.

These poems implore us to lean into the dizzying effects of looking into their kaleidoscopes—“‘a city’s not / worth anything if it doesn’t cause mental illness insanity fearlessness’ (Canal del Norte)” —in order to better see—“¿why run away? ¿where to? it’s not even / clear that there’s anything more than nostalgia (beyond the smog).” They document violent fractures and interruptions—“(the lake was rejected) only we believed the cement lie”— often employing parenthetical phraseology that evokes a lens that sees directly into the city’s ghosts and their whispering remains. Here, deconstruction and reconstruction work in tandem, like a building that has crumbled into itself only to be rebuilt with its own ruins.

Through an accumulation of images, Domingo offers a palimpsest that tells a truer story about what can be seen: “a bicycle’s half skeleton a charred bucket attempting a / grim grin a blue-paint-stained teddy bear a mattress skeleton’s springs.” Each of them encircling the other like the grooves of a record; without one another their song would be impossible. Holding this book, one of 44 in a limited print, one senses the fluidity and delicacy of a grand experiment are being expressed by its gingerly handbound pages. The Spanish text is printed on dense transparencies that can be superimposed upon the English text that is printed on thin cardstock. Between poems, in a cross-disciplinary translation of Domingo’s work, are photographic prints of the translator Ryan Greene’s illuminations of select phrases from the text. Upon further inspection on an accompanying web page, a reader can find video collaborations between the poet, the translator, and a sculpture made of yet other phrases from the book. This skillfully layered and hybridized assemblage is a love letter to Mexico City and to poetry, in all their ephemeral and everlasting complexities and possibilities. (CC)

Maja Haderlap.

Maja Haderlap.

distant transit.

Trans. by Tess Lewis.

Archipelago Books, 2022.

150 pages.

$18.00.

Literary translators often rely on metaphors to explain what our work entails. These range from the infamous and rightly problematized “bridge” between languages and cultures, to a conductor interpreting a musical score, and many more. Maja Haderlap shares another kind of metaphor in the poems in her collection distant transit. In the poem “translation,” Haderlap and Lewis write:

is there a zone of darkness between all languages,

a black river that swallows words

and stories and transforms them?

here sentences must disrobe,

begin to roam, learn to swim,

not lose the memory that nests in

their bodies, a secret nucleus.

Readers of the book in Tess Lewis’ vibrant translation from German (recently named a finalist for the 2023 PEN Award for Poetry in Translation) get to experience this metaphor enacted. Importantly, nearly the entire poem “translation” is built of questions. There is no stable one-to-one transfer of meaning. Something vital happens in that black river, and it’s a slippery transformation.

Haderlap was born into the Slovenian-speaking minority of Carinthia, a border region between Austria and Slovenia that formed the only Austrian resistance to Nazi Germany. She writes through Lewis’ translation that “the border strip / swung back and forth…all is margin / and forgetting and transition.” Reading these poems in English, translated from German, we’re reminded that another language has swirled in the river with them, the Slovenian Haderlap also writes in, and refer to in one poem as “my abandoned language.”

As suggested in “translation,” for Haderlap, language and language loss are also bound up with time and memory. Time takes on a physical quality and becomes a place, a borderland of its own, to be moved through bodily: “i take each word-step unevenly, / worming my way through my time.”

Haderlap’s all-lowercase letters seem designed to help the words slip more unobtrusively into the river and be transformed without snagging on uppercase letters that indicate phrasal beginnings or place names that may be unknown to readers. In this way, they also facilitate Lewis’ inclusion of complex or “inverted” sentence structure in seemingly effortless lines that stretch the possibilities of English syntax productively: “how much the torn-open field i / stand before betrays.”

When remembered words spring to the speaker’s mind, Lewis often leaves them in Slovenian, allowing the reader not only to experience the quality of the language, but also to emphasize the speaker’s struggle to decide whether to “recognize them or spell / them back into silence.” At other times, Lewis defines significant words, while maintaining an emphasis on sound (if not the same sound, then an inventive transformation): for example, “spomin, spominčica, spomenik / memory, forget-me-not, monument.”

Perhaps translation into other languages, allowing the poems to find new readers, is a fitting destiny for distant transit. While occupation determines the speaker’s sense of self in language (“the border tightened / your steel collar”), Lewis’ translation helps accomplish the desire expressed in the lines “my language / wants to be unbridled and large, it wants / to leave behind the fears that occupy it.” (KV)

Paula Ilabaca Núñez.

Paula Ilabaca Núñez.

The Loose Pearl.

Trans. Daniel Borzutzky.

co•im•press, 2022.

148 pages.

$19.95.

It is important to ground Paula Ilabaca Núñez’s book The Loose Pearl in time and space to better understand the work as a treatise both of a time and timeless at once. The text was originally penned in Santiago, Chile in the early aughts (2007) and shared online with an anonymous audience, came into print as Ilabaca Núñez’s third poetry collection in 2009, and had its third coming through the masterful work of translator Daniel Borzutzky in 2022. The Loose Pearl, which is Ilabaca Núñez’s English debut, is about many things but two themes that appear on loop are that of sex and rage. In the pages there is a radical cataloging of heartbreak, longing, and an anger at circumstance that reaches fever pitch. The collection of prose poems opens with the licking of white mares, with fucking and the absence of fucking, with a gold heart split jaggedly down the middle—“And I’m still here, playing fast and loose says the pearl…” (37).

Within The Loose Pearl’s six sections, delineated by pages entirely black and oft adorned with song lyrics, the reader comes to awareness in an orange bed alongside a woman who hasn’t fucked anyone in one month, a fact stated plainly and re-iterated in various colloquialisms. The text moves from here onward through a kaleidoscope of narratives exploring the idea of the split self, the complications of shame and desire, and various forms of birth and rebirth. All throughout, Ilabaca Núñez’s prose is dizzying, beautifully obscene, and blindingly frank. She is unafraid to burr against taboo, to reclaim the body in all its glorious and disgusting realities, to complicate the idea of a woman’s place in the world of want.

I’ll leave you with words written by Ilabaca Núñez, though they appear towards the beginning of The Loose Pearl and not the end. It’s the kind of sentiment that scares and electrifies, and seems apt when living in a world in which women must fight in order to live with full agency: “The party is ending, it’s ending, and it doesn’t matter how shiny the dress was or the makeup, nor how many wanted to fuck or hook up, the same face always remains, the same apathy and the idea of a high-voltage void” (13). (ZCK)

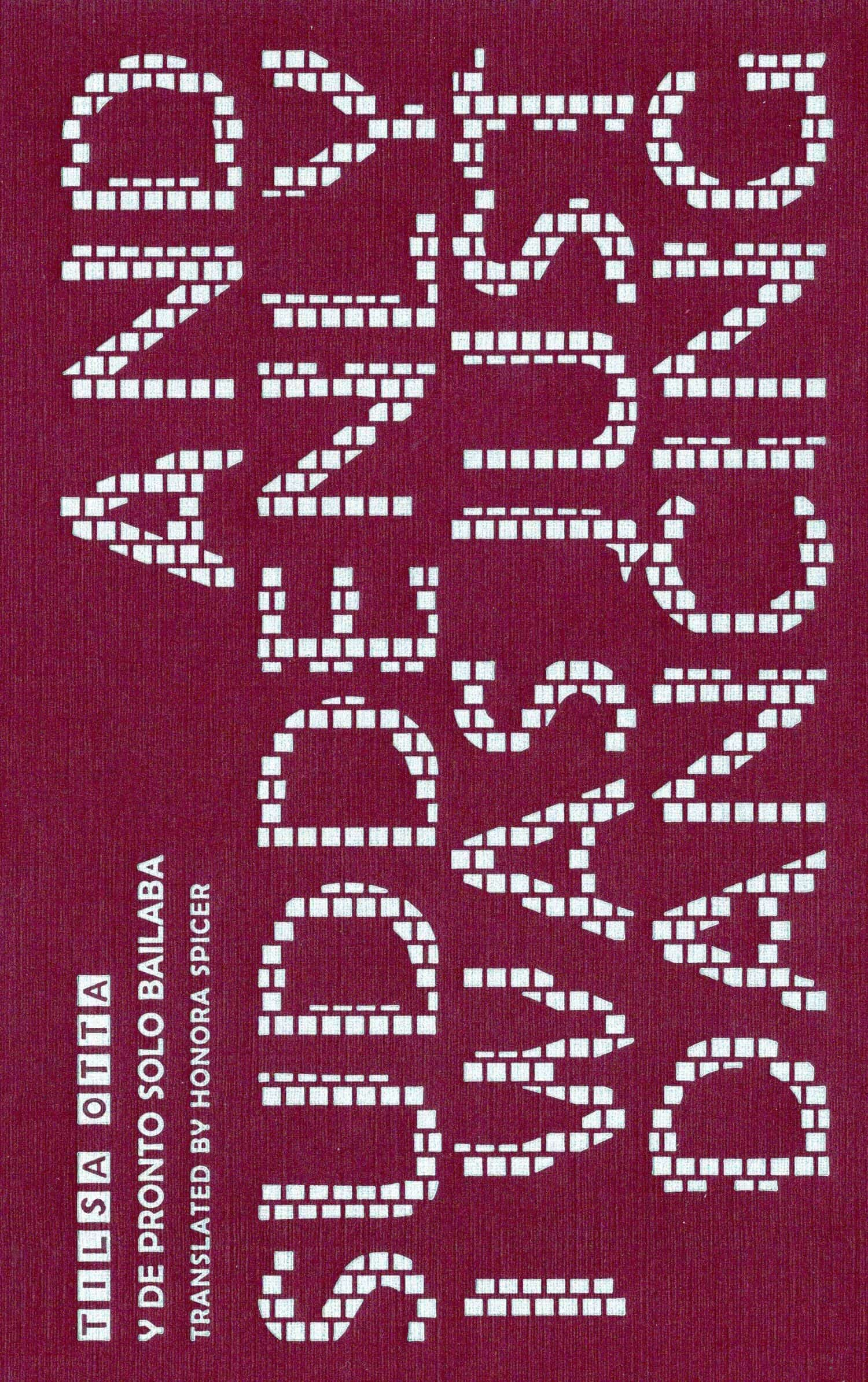

Tilsa Otta.

Tilsa Otta.

And Suddenly I Was Just Dancing.

Trans. by Honora Spicer.

Cardboard House Press, 2023.

55 pages.

$23.00

Tilsa Otta has offered us a vibrant black hole to enter and find ourselves enraptured with And Suddenly I Was Just Dancing. This poetry collection flows to its own beat of queer wonder, interconnectedness, and expansion. Opening with a visual poem that is both map and symbol for the past, present, and future, the poet seems to mark the spot (X) that inspired, inspires, and will inspire in perpetuity an abundance of possibilities (+). As in the poem “Hormone of Darkness” wherein Otta proclaims “I have three X chromosomes but I want + / +++,” alluding to a constructive desire that is vast as it is shameless. Indeed these poems, rendered into English by Honora Spicer, make a reader want more. They invite spacious surrender to the pleasures of connecting with oneself and with others in as much as they lay groundwork for finding a “playground” in a “crazy-sad world.”

The joy and vulnerability of living erotically turn up again and again in the meanderingly organized anarchy of these pages, where longer meditations are arranged alongside fleeting untitled observations. Like a dance, or even love, a rhythm builds in Otta’s poems that explore the club and the human condition with equal measures of autonomy and forthright wonder: “And we can go on and on like that forever / building paradise with our whims / with our fetishes our loves our vices / What luck.” But at no point do these poems avoid the pitfalls and the known limits of the material worlds in which they are set. Instead, they revel there, where growing grass, blooming flowers, copulating wolves, bodies that leak, Carl Sagan, and Lord Byron all dance with one another in the accommodating expanse, as if to say: “This poem is a heaven / so you can live here after dying / with all my heart.”

In “Definitive Animal,” the speaker’s charge to the wolfdog to “Transcend the anal quest and save the day,” “Nationalize yourself,” and “Inscribe your laughter onto sheepskin” echo infringement and violence that enforced definitions provoke against the nature of the politicized queer body. Likewise, these moments harken back to an earlier poem’s nightclub scene among “police disarmed and reassembled” wherein we can wonder “who put an orifice where there was a law / A cock where there was a whistle”? Laid bare, perhaps the questioning nature of these scenes and bodies are what make “The stoplights blush so red,” invoking the potentiality to flip anything on its head.

Throughout the collection, Otta candidly points out where tensions—“The editor will cover the intimate parts / With black holes”—might hand us our agency—“Never forget / There are planets in other lives.” In this insistence to turn to the other and to possibility, there is a pervasive intimacy in Otta’s work that is further enhanced by the literal feel of the book in one’s hands. This volume is one of a series made by the Cartonera Collective in the democratizing style popularized throughout Latinoamérica. It is bound by hand, with two sewn folios fastened between two pieces of cardboard. Sturdy for now, but in time who knows? This book is an object—“When I heard for the first time that woman is an object / I professed a bulletproof love for objects”— that reminds us to uplift the coexistence of what can be chosen with what cannot, and invites us to appreciate it all at once. (CC)

Zoe Contros Kearl is a writer and editor based in Vermont. Writing appears in Be About It, Entropy Magazine, HAD, Maudlin House, Neutral Spaces, The Quarterless Review, and elsewhere. ZCK currently serves as Nonfiction Editor for American Chordata Magazine.

Cristina Correa is the recipient of awards from Washington University, Kenyon Review, CantoMundo, Hawthornden Literary Retreat, and Cornell University, among others. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Prairie Schooner, Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day, Best New Poets, Missouri Review, Obsidian: Literature & Arts in the African Diaspora, and elsewhere.

Kelsi Vanada’s most recent translation is The Visible Unseen, a book of hybrid essays by Mexican writer Andrea Chapela (Restless Books, 2022). Kelsi is the Program Manager of the American Literary Translators Association (ALTA) in Tucson, AZ.