curated by Katherine M. Hedeen

Reviewing poetry in translation

- recognizes translators as authors

- destabilizes narrow definitions of originality, authenticity, and authorship

- makes visible the artistry of translation

- is dissent, defiance, disobedience, subversion, solidarity

Where better than the Action Books blog to do the work?

Microreviews of poetry in translation coming at you every few months right here!

Maya Bejerano, Sharron Hass, and Anat Zecharia.

Maya Bejerano, Sharron Hass, and Anat Zecharia.

A Winding Line.

Trans. Tsipi Keller.

Zephyr Press, 2023.

182 pages. $20.00

This morning, the moment is an ongoing present,

a winding line and you a guest in it, a guest who’s inclined to walk,

who set out to explore – (Maya Bejerano)

In A Winding Line Tsipi Keller extends an invitation to English-speaking readers to “set out to explore” poetry from three influential and innovative poets, Maya Bejerano, Sharron Hass, and Anat Zecharia, who are all considered vanguards of contemporary Israeli poetry. This collection of poems, most of which have been published within the last decade, offers intimate glimpses into the human experience, showcasing the interior worlds of our modern life. Keller skillfully captures the distinct voices and insights of these three poets, while also highlighting the introspective nature, boldness in addressing provocative themes, and ability to craft incisive observations present in each of the three poets’ works.

We’ve built kingdoms towers and homes

upon dreams and iron and greed

having learned to inhale the emptiness

as if it were a sea or a field

as we retain our anal proclivities to survive. (Anat Zecharia)

Like a mirror, this collection of poems moves the reader to witness their own reflection in the fragile and captivating landscapes of this ongoing present. In doing so, this book acts not only as a testament to the growing legacy of the three poets whose work is featured in its pages but also as an ode to the power of language, art, thought, and poetry; all of which are very much active and alive today in Israel’s contemporary poets. (SS)

Kim Haengsook.

Human Time: Selected Poems.

Trans. Jake Levine, Susan K, Léo-Thomas Brylowski, Hannah Quinn Hertzog, Joanne Park, Soohyun Yang, Soeun Seo, and Jiyoon Lee.

Black Ocean, 2023.

120 pages. $17.

As the first English-language collection of Kim Haengsook’s poetry, Human Time encompasses twenty years of the poet’s career as selected by the poet herself. Across its four sections, her work extends throughout the “in-between” of what she positions as being and not being contractions; life and death, love and the grotesque, space and time, prose and lyric poetry, and the act being and not-being itself. (Levine 12). Such as in “Dear Angel,” Kim traces these connections between people and between life and death along winding tails, train lines, echoes, rivers, and waves:

I said there are trains drawing curves underground in the city and I said in the train there

are long chairs. I told her the story about how the whites of the eyes of the people who sit

on long chairs disappear. It’s as if they’re dead like people in heaven.

…

Do you love humanity? I asked. I’ve been waiting for the response.

Even while considering collective and personal or autobiographical experience, Kim’s poetic voice resists claiming an individual ownership over these life experiences. This is advanced further by the communal translation of Human Time. After the poems in the collection were initially divided amongst Jake Levine, Susan K, Léo-Thomas Brylowski, Hannah Quinn Hertzog, Joanne Park, Soohyun Yang, Soeun Seo, and Jiyoon Lee, all subsequent decisions for each translation were made collectively the eight translators.

Kim constantly reaches out, writes down, or speaks not only to those around her but also other writers, texts, and media throughout history, from Kafka himself and Metamorphosis to Ernest Hemingway and the Alejandro Jorodowsky film Sante Sangre. Like in “Adam’s Joke,” she writes throughout each section of the collection, she writes in order to grapple with and preserve each question she poses, each observation on not just her own life but collective experience:

If I was made only from things that were left behind, would I forget myself entirely? If

there’s something to say that I remember but nearly forgot, I need to write it down before

I forget it again. Could you remember it for me?

Just as Kim’s poetry positions a multitude of influences across time and media collectively determining our human experiences, the communal translation of her work resists the individual ownership of one poet or one book as well. Kim’s work challenges the commodification of human experience through her writing, and the translators furthers this by challenging the commodification of hers and their work. After collapsing time in the final poem in the collection “For Whom the Bell Tolls” with “We’ve been children since forever. / Dangerously,” Kim once again rejects this individual ownership over human experience while her speaker collects the disembodied hands that recur throughout her poetry:

One day my hands feel like an orphaned object.

I pick up a hand on the street

and when I take it out of my pocket in the evening, I’m starving.

I think my black pupils slowly turn white.When I gather my hands in the evening

everyone’s hands look the same.

(SP)

Eleni Kefala.

Eleni Kefala.

Time Stitches.

Trans. Peter Constantine.

Deep Vellum, 2022.

216 pages. $15.95

In Eleni Kefala’s Time Stitches, the threads of time running through the collection are tied together at one central mast: the story of a man from a small village in Cyprus, drawn from his birth to his eventual emigration to England at the dawn of World War II. In an interview with Peter Constantine, translator of Time Stitches, Kefala explains that “. . . the twenty-six fragments where we hear the voice of the Cypriot man are the womb from which everything else in the book originates.” This man—Kefala’s own grandfather—writes in a unique “hybrid idiom” comprised of the standard Greek that he’d learned in school and the local dialect of his village, resulting in misspellings and mistranslations that act as a buoy for the next thread of poems to find air.

First reading this collection, I found myself rather lost, even with a clear outline of the plots provided in the foreword. Each stitch is short, sometimes barely even a full thought, sometimes dense with historical detail, and always divorced from the rest of its thread. There were points where I was frustrated by the lack of clarity—jumping from moment in time to moment in time, I felt in a way strung in between them, unable to find where the stitches come together. I realize, though, that this is in part the experience we are meant to have when reading Time Stitches. Again in conversation with Constantine, Kefala says, “Time Stitches relies strongly on the reader, who’s tasked with putting the jigsaw puzzle together . . . I often imagine the book’s structure, its scaffolding, as a shattered piece of glass or pottery. The reader must recreate it through multiple readings. Of course, not all readings are—or even can be—the same. Personal and cultural perspectivism is always crucial.” I had been reading Time Stitches as an uninvolved observer; the truth is, we are meant to bring our own thread to the collection, and perhaps stranded between moments of time—“playing hopscotch within the gaps of history,” in the words of the opening line of the collection—is exactly where we’re meant to be.

Time Stitches focuses heavily on translation and linguistic differences, with the linguistic mistakes of the Cypriot man carrying us to each thread of time, and bringing this into English serves a considerable challenge. Peter Constantine’s translation is attentive to the various registers and dialects throughout Kefala’s poetry, and the voice of each thread is impressively real. On another level, Χρονορραφία in its original writing is its own work of translation—once again from the interview that has served as such inspiration for this review, Kefala says, “. . . the idea of the writer as translator and carrier of contexts and meanings . . . appears to be a guiding principle in both my poetry and research.” In carrying contexts and meanings across cultures and tongues, Kefala’s poetry draws these disparate worlds together. In Time Stitches, these lives that couldn’t be further apart—whether in time, distance, or language—are brought to find and reflect one another, sewn together in poetry. (BC)

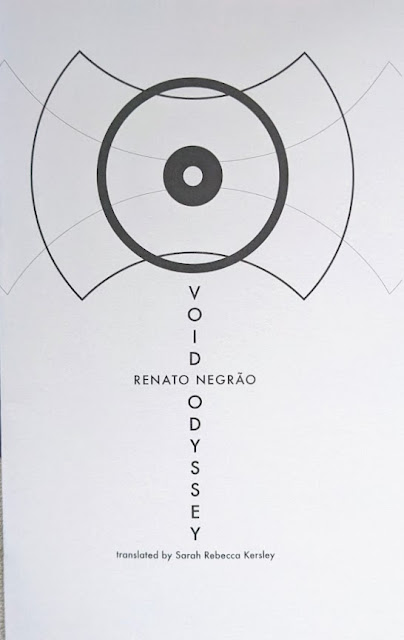

Renato Negrão.

Renato Negrão.

Void Odyssey.

Trans. by Sarah Rebecca Kersley.

Toad Press, 2022.

18 pages. $6.

Renato Negrão (b. 1968) is a Brazilian poet, composer, performer, and visual artist whose innovative work explores the relationship between the written word and image, sound, space, and form. His poetry follows in the tradition of Brazil’s Concretism movement, started by Décio Pignatari and Haroldo and Augusto de Campos in the 1950’s, which comprehends the poem as a three-dimensional entity constituted not only by word and sound, but also by its visual form. Brazilian Concretism led to other experimental poetic movements, noteworthy among them the Poema-Processo, which emerges in the country in the late 1960’s. In this movement, the poem acquires the status of object, and the word may coexist with—or even give way to—geometric forms, dots, and other typographical symbols.

Some of Negrão’s works, such as Void Odyssey (Odisseia vácuo), evoke the best examples of Poema-Processo. At the same time, his oeuvre is unique and groundbreaking in many ways, particularly in that it is often performative; in other words, performance and the body are central to Negrão’s writings, videos, and installations.

Odisseia vácuo initially appeared in 2016, in a limited edition as a “livro-objeto” or “book-object,” a work that is both a printed book and an object of art that can be manipulated and looked at/read from various perspectives. It is comprised of one single poem, as is the English-language edition. If the book-object generally seeks to push the physical limits of the traditional printed book and of the text it carries, Negrão’s poem pushes the limits of poetry and poetic communication by relying not only on the word and sound, but also on silence and on the empty space of the blank page:

“the oeuvre of

served as a foundation for all other works that would later arise in a

period of over

for over a

whilst in fact, all that was being done was a repetition of the same rules,

almost always in the same disposition, varying only in the part relative to

the practice of thein the subsequent period, the following authors appeared

of all of them, the most

and who contributed somewhat

more towards the development of

the

is[ . . .]

later on, many other authors wrote on the subject, varying only the

part about the”

The reader follows the poetic voice on an odyssey through ellipses, echoes, emptiness—the void, as referred to in the title. The pursuit of meaning may be in vain or endless, as Negrão teases and challenges us, hinting at a wide range of possibilities, and even questioning the idea of originality and authorship. As Void Odyssey rejects any attempt at a fixed reading, it would fit perfectly in Jorge Luis Borges’s “Library of Babel,” wherein only one certainty exists: that “everything has been written” before.

Sarah Rebecca Kersley, an experienced translator, and a poet herself, skillfully captures the rhythm, style, and nuances of Negrão’s poetry, offering the English-language reader an important example of the author’s provocative work. (CPB)

Bella Creel is a blog editor at Asymptote Journal and an English teacher in Hyogo, Japan. She can be found on Twitter at @isabella_creel.

Sarah Pazen is a poet, translator, and visual artist from Chicago, Illinois. She is currently a Fulbright Fellow to South Korea, and her work has appeared and is forthcoming in EX/POST Magazine, The Tulane Review, BreakBread, and more. She can be found on Twitter @COPINGSKILLS.

Cristina Pinto-Bailey is a writer, scholar, and translator. Her work has appeared in Latin American Literature Today, Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas, and elsewhere. She translated Maria Firmina dos Reis’s 1859 abolitionist novel Ursula (Tagus P, 2021) and is currently translating Maria Valéria Rezende’s 2016 novel Other Songs.

Shanti Silver enjoys exploring media from across the world, spending time with friends and family, and pointing out particularly cool flowers on walks around the city.