1.

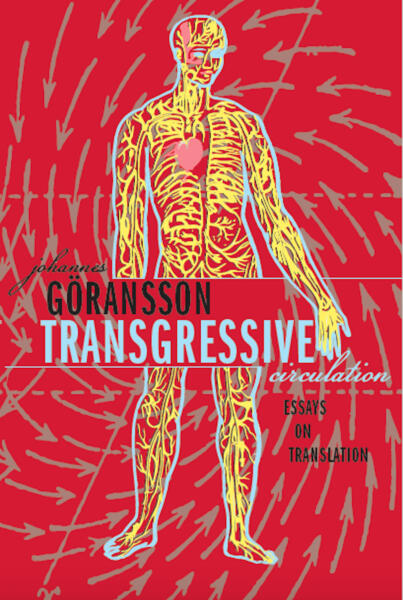

In Transgressive Circulation, my book about translation, I draw on John Durham Peters’ book, Speaking Into the Air. Peters argues that western culture developed an ideal of “communication” in reaction to the onset of mass communication, an ideal of “direct contact between interiorities.” I argue in the book that this anxiety about mediation and excess has to a large extent shaped our literary culture’s denigration of translation – as what’s “lost in translation,” or, better yet, lost in mediation, proliferation, deformation zones. In this post I’m going to draw a connection between these zones of translation and another mode – ekphrasis. And how in these zones ekphrasis becomes occult.

2.

Peters argues that 19th century spiritualism comes out of this same nexus of “communication”- coming out of a desire to make direct contact – not with fellow living humans but – with the dead. On one hand these occultists sought to find direct access to communicate with the souls of the dead. But I’m interested in the way they often foregrounded the mediumicity of the channeling, often to the point of spectacle. Think of the “ectoplasm” emitted by women’s bodies, the double-exposure ghost photographs, all the props (dolls, ouiji boards etc.) that became associated with this form of dubious communication.

3.

Lately the occult has become associated with astrology (as in “the Astropoets”) and a lot of self-care. But I liked Dan Chiasson’s description of Joyelle McSweeney’s occult (of her book Necropastoral: Poetry, Media, Occults as well as her new book Toxicon and Arachne):

As occult ideas about poetry go, McSweeney’s is surprisingly grounded: poetry isn’t a séance, as it was for Yeats or James Merrill; it’s a biohazard, teeming with linguistic contagion.

Rather than the idealized communication of Yeats – where spirits speak to him and reveal the truth – Joyelle’s occult moves ultra-mediumistically. Or it is the medium. Like a contagion. Rather than reinforcing personhood, this is an occult of toxicity. The occult is in the foreign influence, the breaking of boundaries, the transformation of the self, the body.

4.

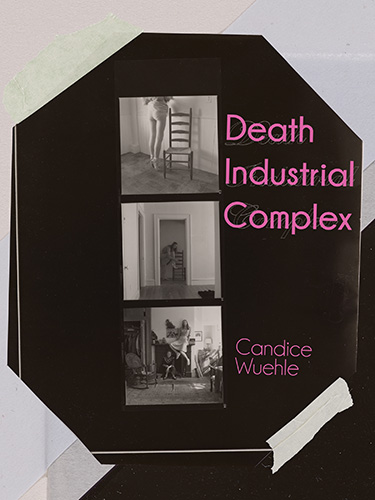

Candice Wuehle’s Death Industrial Complex (Action Books, 2020) is a booklength engagement with Francesca Woodman’s photographs. But it’s not the expected act of ekphrasis where the poet sees a painting and writes a poem about it. The relationship is much less clear-cut. That’s because this book is an act of occult ekphrasis. It teems with linguistic and visual contagion. Like the spiritualists of 19th century, it communicates with the dead, but not “directly” because in this occult ekphrasis the medium becomes thick, anarchic, spectacular – a deformation zone.

5.

The book has already received some really insightful reviews. In a review in Heavy Feather Review, Mike Corrao writes:

Candice Wuehle’s newest book, Death Industrial Complex, is a collection of ekphrastic poems made in conversation with the works of Francesca Woodman. Before reading the book, I had not known this. I was unfamiliar with the artist and her work. But throughout the course of my reading it always felt as if there was something looming in the background. The constant presence of mirrors and notes on fashion. The book often feels like a reflection of another medium. As if Wuehle has projected the photographs over each page as they were assembled. Building the text from the ground up as a manifestation/recycling of the photographic image. Converting every component of the latter into the former.

Elsewhere in the review, Corrao talks about the cloaking, cadavers, recycling, glitches and ghosts. I love how the poems in Corrao’s reading become hyper-mediumized, but also dynamic, convulsively ambient: what is in the background becomes the foreground; things are converted into component, things overlay each other.

6.

Throughout the book, surfaces become convulsive deformation zones, as in the beginning of “self-portrait talking to vince”:

I was charged with conspiring to pervert

the appearance of nature. I made a field

of carnations black

and white. Even vince isn’t talking

to me anymore so I arc my spine and tilt

my chin until his innards are exposed in a spiral

coiling from the O of my mouth. There is a functional

telephone inside my stomach, there

is no way for vince or anyone to hang

me up…

This poem ekphrasizes one of Woodman’s most iconic photographs, “Self-Portrait Talking to Vince.” Its’ an interesting title – removing the usual self-centeredness of self portraits by adding “Vince” into the equation, the “talking” corrupting the self-ness of the self-portrait.

As the poem suggests, the picture shows a spiral coming out of her mouth, as if to make the words tactile. The spiral is the communicative act turned tactile – like an ectoplasm – a perversion of the act of communication, something that is emphasized by the jarring line-breaks. There’s a spiritualist telephone inside her stomach.

7.

The title is also particularly curious since the “self” presumably refers to Woodman, but by naming her poem after Woodman’s photograph, Wuehle makes a double of the self. In his review of the book in the journal Empty Mirror, Tom Snarsky argues that what Wuehle’s doing is closer to “cloning.” I like how in both of these responses (Snarsky and Corrao), the reviewers describe a poetry that doesn’t follow the communication ideal, but rather follows a gothic logic of doubling. Wuehle doesn’t see then recreate, depict. To bring back Chiasson’s description of McSweeney’s necropastoral: there is constant infestation, transformation, intoxication, contagion of the surfaces. In “cryptobeauty // giantess,” this kind of “cloning” is at first literalized:

You are going to know what i am saying.

You are going to understand me.

vince, make a list of everything i will eat:THE LIPSTICK THE MOUTH THE TELEPHONE THE SMOKE WITHIN THE SCRYING STONE THE WAX THE HONEY THE HIVE THE HAIR THE TAN LINES THE MIRROR THE MOUTH THE STAIN FROM THE MOUTH THE JELLY THE TRAIL OF THE GASTROPOD THE LIGHT THE DARK THE OPENING OF THE CAVE THE COLOR DARK THE COLOR SILVER THE COLD THE COLOR GOLD THE STICKINESS OF TAPE THE INTERSTITIAL KISS THE SAP THE SKIMMED FAT THE FAT THE SECRETION OF THE LIPS THE OIL THE EXTRA SKIN THE DUST THE PROFANE DUST THE SACRED DUST THE EXTRA STARS THE DUST

This foreign entity that interrupts “talking to Vince” with what appears to be a myriad of trinkets, possibly from a fashion-shoot. That most deadly of genres.

8.

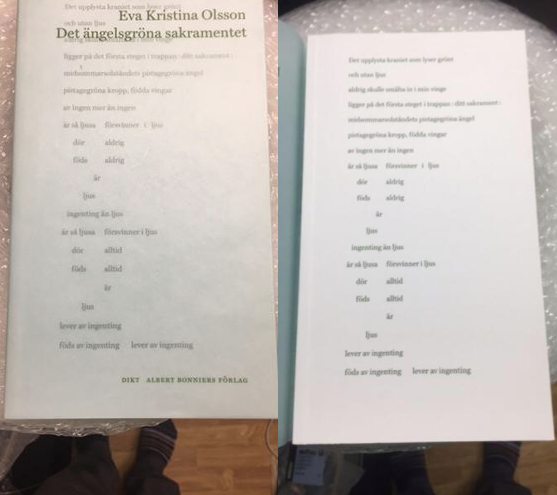

There is a similar media-disturbing (poltergeist = disturb-ghost) going on in Eva Kristina Olsson’s book Det ängelsgröna sakramentet (which I mentioned reading in my first post) – The Angelgreen Sacrament – a book that depicts an ultra-erotic, physically intense encounter with an angel. In her review of the book, “Sweden’s Craziest Poetry,” in Svenska Dagbladet, Viola Bao provides a great descriptions in the article

What kind of poetry is this? That’s the question I think of having read Eva Kristina Olsson’s latest poetry collection, The Angel-Green Sacrament, a strange short, intensive text dressed in green-hued parchment paper. The poem is chant-like and ritually repetitive. At first it appears to something like a sacral hymn or a liturgical meditation of a number of religious symbols, but the language gradually begins to resemble madness or a bizarre fever dream.

I like this description because it captures the occult mood, the way the book’s woundedness leaves us lost (“What kind of poetry is this?!”), and the importance of textures.

9.

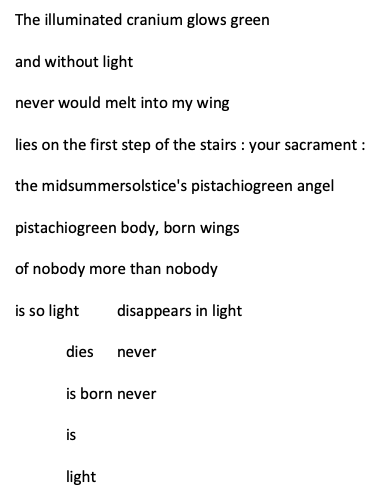

The mediumicity of the book begins with the very design: the “cover” is a thin, transparent, green parchment paper through which the first page of the book is visible. This must be what “angelgreen” looks like – you see through it, but not entirely – and it makes me feel like the book is the angel’s body. By turning the pages, we enter into the angel’s body, the poem:

As the poem comes to resemble “madness or a bizarre fever dream,” it becomes unclear if the “voice” is the voice of the angel or the poet – or if the speaker has been taken over, infected by the angelic – this is the angel of the necropastoral.

10.

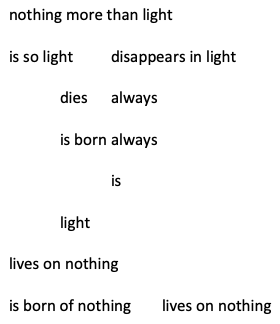

Olsson’s angelic encounter is (as in Rilke’s famous poem) both terrifying and beautiful:

I am born only this one time

you see me only this one time

one time I am angelgreen

never again

always

never one word

only the lips’ tears

I drip over your birth’s

voice in the room

corroded by angels

There’s a repeated mantra that seems to both threaten and soothe the poem, the angel, the poet: “you are not afraid / don’t be afraid/ be afraid / don’t’ be afraid.” Or: It feels almost like a guide into the fever dream is telling the reader to keep going. Into the wound.

11.

The poems in this collection may not be explicitly ekphrastic, but Olsson’s description of her angelic encounter follows Timothy Morton’s description of a kind of ambient ekphrasis in his book Ecology Without Nature: “Ekphrasis suspends time, generating a steady state in which the frequency and duration of the form floats wildly away from the frequency and duration of the content.” To go back to my quote from Aase Berg writing about Eva Kristina Olsson (from my post a week ago): Occult ekphrasis rejects the scar, leaves us in the wound. And in that wound, the narrative is lost in ambience: we are afraid but ecstatic.

Johannes Göransson is the author of four books with Tarpaulin Sky Press — Entrance to a colonial pageant in which we all begin to intricate (2011), Haute Surveillance (2013), The Sugar Book (2015), and Poetry Against All (2020) — in addition to three previous collections of poems: A New Quarantine Will Take My Place, Dear Ra, Pilot (“Johann the Carousel Horse”) He has also translated several books, including Aase Berg’s Hackers, Dark Matter, Transfer Fat, and With Deer as well as Ideals Clearance by Henry Parland and Collobert Orbital by Johan Jönson. @JohannesGoranss