The Silence (1963) Directed by Ingmar Bergman

1.

Gertrude Stein famously said she went to France to be alone with the English language. I was never alone with the English language. I never wanted to be alone with the English language and the English language never wanted to be alone with me.

2.

I first started to speak/read/listen to English while growing up in another country and when I came to the US as a teenager I was in an ESL classroom with students from Vietnam and Latin America. I came to the US in a very multilingual space that contained languages and experiences from outside the official English, including places of US imperialism and war. None of us were ever alone with English.

3.

In a sense I did come to be alone with the Swedish language later in my life. For years in my early twenties, I barely interacted with anybody who spoke Swedish. My Swedish became at a mixture of the ultraliterary and the Swedish of a 13-year-old. But I was never alone with it. The English was there with us, infecting my Swedish like a disease. I would venture that the same is true of Stein. I bet those other languages – the French of her surroundings, the German of her childhood – were there all along, infecting her English with strangeness.

4.

I’ve always been homesick. My whole life people have asked me when I would get over coming to the US and just become an American. The American ideal of “the good immigrant” – who came to the US and never looked back as they forged ahead (pushing Native Americans out of the land as they traveled) was a way of both pathologizing and eliminating homesickness, a disease that interfered with the conquering of America (many immigrants suffered from this disease, many even died from it). So I have returned to Sweden, to Swedish poetry over and over. It’s infected my English.

The Silence (1963) Directed by Ingmar Bergman

5.

In Translation is a Mode=Translation is an Anti-Colonial Mode, Don Mee Choi reads Ingmar Bergman’s The Silence as a parable about translation. One twin sister, Anna, is healthy – sexual, reproductive – but the sister who translates is sick (sweaty, chain-smoking). The sisters and Anna’s son Johan are traveling through a strange land (in the middle of a civil war of some kind). As Choi notes, there’s a bond between Ester, the translator, and her sister’s son, Johan. “Anna’s son, like his Aunt Ester, is prone to foreign words and, therefore, homesickness.” Paradoxically, this “homesickness” is also a kind of away-sickness, because, Choi argues, both Johan and Esther become “foreign” through their interest in translation. Their sickness is a kind of foreignness entered through language.

The Silence (1963) Directed by Ingmar Bergman

The Silence (1963) Directed by Ingmar Bergman

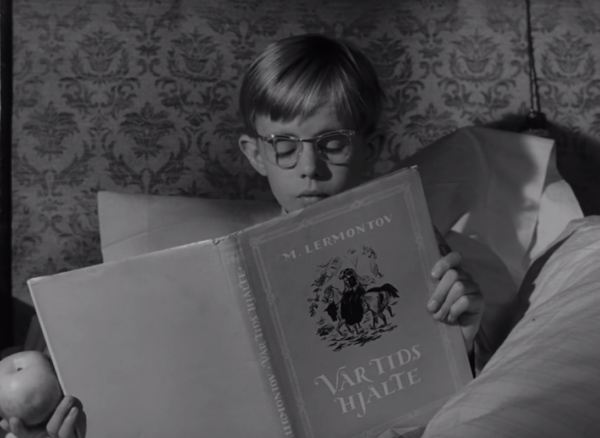

6.

Toward the end of the movie, Johan is in bed reading a Russian novel in translation. As Choi notes: “He has become a foreigner like his translator aunt.” We tend to think of the act of translation as necessarily “domesticating,” but it seems to me that Choi here is making a radical shift in that paradigm. It’s not just that the translator “domesticates” the foreign text into another language, it’s also that the process brings them into the other culture. Translation foreignizes the translator.

7.

(For both me and Choi, this process is somewhat complicated by the fact that we are immigrants and are actually bringing our “native” cultures into our “second languages.”)

8.

Choi’s own book is a book about anti-colonialism, homesickness, translation. She cannot let Korea be, and in the process she not only draws attention to the transnational, neo-colonial relationship between the US and Korea, she also foregrounds a culture as multiplicity and potentiality – she is maybe partly Kim Hyesoon’s twin, but more importantly, she’s her own twin, her non-emigrant version. In the US we want only to have the one true version. One we introduce twins, we ruin the gold standard of selfhood. We become sick translators, engaging in a sick poetic process.

9.

Why is translation such a sick act?

In her essay “Bilingual Games: An Invitation,” Doris Sommer writes about the importance of experiencing multiple words for the same things:

“More basic than these hide-and-seek games is the fact that overloaded systems unsettle meaning. When more than one word points to a familiar thing, the excess shows that no one word can own or be that thing.”

Or as she writes a little later in the same essay:

“Words are not proper and don’t stay put; they wander into adjacent language fields, get lost in translation, pick up tics from foreign interference, and so can’t quite mean what they say. Teaching bilinguals about deconstruction is almost redundant.”

In difference to the New Critical paradigm of the “wellwrought urn,” the process of translations call attention to this “excess”: the idea that no one word can own or be “that thing.” Instead the words vibrate in an excess of unsettled meanings, leaking into the English language.

10.

This leaky, vibrating zone is what translation makes of poems: deformation zones.

Johannes Göransson is the author of four books with Tarpaulin Sky Press — Entrance to a colonial pageant in which we all begin to intricate (2011), Haute Surveillance (2013), The Sugar Book (2015), and Poetry Against All (2020) — in addition to three previous collections of poems: A New Quarantine Will Take My Place, Dear Ra, Pilot (“Johann the Carousel Horse”) He has also translated several books, including Aase Berg’s Hackers, Dark Matter, Transfer Fat, and With Deer as well as Ideals Clearance by Henry Parland and Collobert Orbital by Johan Jönson. @JohannesGoranss