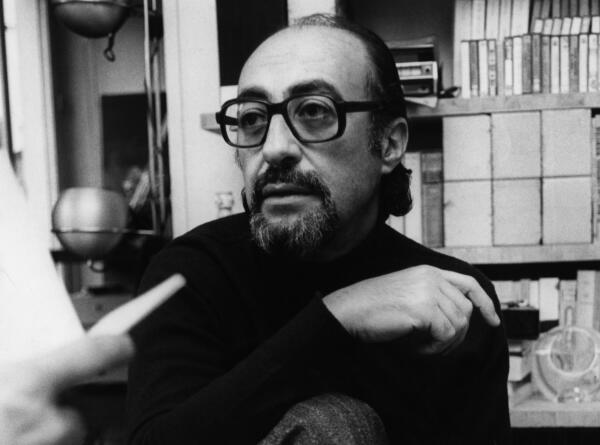

Jorgenrique Adoum

Olivia Lott: Let me first say how excited I am about this book! Adoum is one of those essential poets everyone should know, but few do. Being from Ecuador, as you write in your translator’s note, he is also overlooked in the Spanish-speaking world. How did you first encounter Adoum’s poetry and what led you to translate it?

Katherine M. Hedeen: Thank you for your interest in the book. You’ll have to forgive a somewhat long answer to a fairly straightforward question, but prepoems in postspanish is actually just the tip of a large iceberg. Originally Adoum was part of a larger project that my co-translator, Víctor Rodríguez Núñez, and I envisioned in the late nineties and that eventually became a series with Salt Publishing in the UK. The idea for it began because we are both specialists in contemporary Latin American poetry. Adoum’s generation of poets (Juan Bañuelos, Juan Calzadilla, Roque Dalton, Juan Gelman, Fayad Jamís, just to name a few) is one that has marked us deeply and we soon discovered that very few had been translated into English. They simply didn’t exist and the point of our project was to make them better known in the English-speaking world.

Víctor is a well-known Cuban poet, who had been a recognized cultural journalist and critic before coming to the US in the mid-nineties, so he knew most of these poets personally, including Adoum. I was an emerging scholar studying poetry and just beginning to translate. We had met as graduate students in the Department of Romance Languages at the University of Oregon and soon after continued our graduate work at the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at the University of Texas at Austin. One of our biggest obstacles was that, at the time, translation was highly discouraged in the academy (it continues to be, but not to the same degree). As graduate students we were warned to not “waste time” on it, when we could be writing academic articles, which would guarantee our success as professors. Honestly, it was never even that direct of a message; it didn’t have to be. There was no question that any creative endeavor would only hinder your chances of getting a good academic job. Serendipitously, we were hired as professors at Kenyon College in the Modern Langugages and Literatures Department. At Kenyon, we met some creative writing folks in the English Department, namely John Kinsella and Janet McAdams, who were very supportive of the idea of a Latin American poetry in translation series. Janet invited us to be a part of her Earthworks Series of Indigenous Poetry for Salt Publishing and we ended up bringing a number of really important contemporary poets from Latin America into English for the first time. It was an absolute school for me. I still find it unbelievable that the first book I ever translated was Juan Gelman’s The Poems of Sidney West. I’m very proud of the groundbreaking nature of the series and to have gained much of my experience as a translator working with some of the most remarkable poets of the second half of the 20th century. I’m not nearly as proud or satisfied with the translations themselves and it’s quite embarrassing to look back on them. I’ve learned a lot since then.

Adoum was originally going to be a part of the series. There were two main reasons he wasn’t. First, if I’m being honest, I didn’t completely understand his poetics and rather than tackling it head on, I just brushed it aside. Secondly, being an academic made it easy to do so. I did not dive deeper into translation until after receiving tenure and I only went to the deep end after becoming a full professor. As I grew as a translator, I returned to Adoum and it became very apparent to me how extraordinary his poetry was. I thought perhaps the NEA would be enthusiastic about the possibility of funding the translation of an Ecuadorian poet, whom Neruda had called the best poet of his generation, and yet no one knew. I was awarded a translation grant in 2014. All this coincided with some major social changes that had taken place in Latin American countries like Bolivia and Ecuador. These progressive changes had brought about a renewed emphasis on Ecuadorian culture in Ecuador itself. This, in turn, fostered—and has continued to foster—a vibrant poetry community there, including the creation of some fantastic poetry festivals. It was a crucial moment for Ecuadorian pride in Ecuadorian art and, since I had studied abroad there in the early 90s, I wanted to be a part of it, as much as I could. In 2014, Víctor and I participated in one of these festivals and that’s where we met Adoum’s daughter, Alejandra. Meeting her, spending time with her, and seeing her own passion for her father’s poetry sealed it for me.

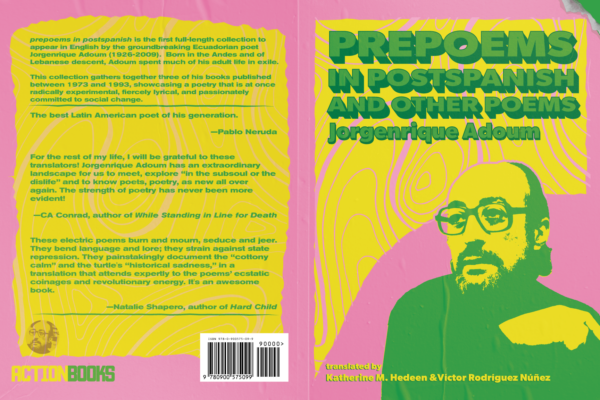

prepoems in postspanish and other poems by Jorgenrique Adoum (Action Books, March 2021) | Translated by Katherine M. Hedeen and Víctor Rodríguez Núñez

OL: I’m glad that you mention the Salt Series as your school because it has also been a hugely important school for me, both as translator and poetry scholar. What I see across those books is a project to recover the centrality of these poets, most of them belonging to the neo-avant-garde, for Latin American poetry through translation. Could you tell us more about what draws you to the neo-avant-garde as a translator and where you see prepoems within it?

KMH: The poets of the Latin American neo-avant-garde are often overlooked for a number of reasons, both in Spanish and in English. On the most obvious level, their counterparts in prose are the “Boom” writers, so some readers think they know enough about Latin American writing in the sixties, after having read for example, García Márquez or Vargas Llosa. Then you have readers who are more interested in, say, Bolaño or more contemporary prose writers. This problem is only exacerbated in English, where access to writing in translation is even more limited and limiting (going into detail about that would mean a whole other interview). In any case, as it often happens, poetry isn’t really a part of the conversation.

Taking it one step further, the neo-avant-garde’s poetic project proposes to break down the false dichotomy of socially-committed content versus experimental form. The Cuban Revolution in 1959 had called Latin American intellectuals to be committed to social transformation and these poets answered that call, passionately. Yet, they insisted that their poetry be both revolutionary in terms of what they wrote and HOW they wrote it. They believed that poetry must be “dialogical” (as Víctor has called it on numerous occasions), requiring an active reader, one who is a co-creator of the work. This approach to poetry profoundly challenges conventional aesthetics in Latin America, where, in general, either you are writing in an accessible way for a wide audience about topics of social and/or “universal” importance or you have opted for a hermetic, not-easily-understood style that signals your own reactionary politics. As scholars of contemporary Latin American poetry and its relationship to social transformation, Víctor and I are drawn to the complexities that the neo-avant-garde’s approach entails.

The neo-avant-garde’s refusal to make things simple is precisely what attracts me to it as a translator into English. A U.S. readership’s idea of poetry from the region can be quite narrow, due to a small but very established canon that overemphasizes emotion, sensuality, and/or political commitment in terms of content. This, in turn, privileges a direct, immediate tone, one that often engages with the expectation that Latin Americans have a more intimate (“primitive”) relationship with nature, sexuality, violence, poverty. It leaves little room for the cerebral. The neo-avant-garde—and particularly Adoum’s poetry—boldly challenges those kinds of assumptions, which are ultimately informed by a neo-colonialist vision of how Latin Americans “should” write.

OL: That’s exactly what most stands out to me in both languages of prepoems: a refusal to make things simple, to present language as clear-cut. Your translation avoids any neat smoothing-over—there’s no glossing, no footnotes, no explanation. To translate a text so dense in neologisms and linguistic experimentation, combined with the broader interplay of destruction (post) and renewal (pre), is quite the undertaking. How did you approach the task of making postenglish?

KMH: In 2009, Adoum’s call to write in “postenglish” was the very reason I didn’t want to translate him! As my confidence as a translator-poet grew, I began to realize that formal experimentation wasn’t an obstacle, it was actually the thing that allowed me to be the most creative, and, at that point in my professional life, I was ready to embrace it. I found in Adoum’s creation of a postspanish the possibility to rework English, and more than that, to break it down, to tergiversate (as I write in my translator note), to rebel against its linguistical constraints, and—precisely through language—to attempt to defy the imperialist, neo-colonialist limitations of it. This to me is an essential part of being a translator. I have Adoum to thank for leading me one step closer in the articulation of it.

With postspanish, Adoum refuses to follow rules: the grammatical rules of an imperial language, for instance. The reader is immediately confronted with all kinds of neologisms based on the invention of compound words, the creation of verbs from nouns, constant wordplay and soundplay, things of this nature. There’s also an emphasis on intertextuality, appropriating language and discourse from the social sciences, from journalism, etc. And an obvious rejection of the rules of Western rationality, too. Many of these poems do not “make sense” in the way that readers might expect. They are not conventionally thematic or topical, things are often not conveniently resolved by the end of a poem. All of these elements are obviously challenging for the translator.

OL: I appreciate that your translation emphasizes this rebellion, against language, against “making sense,” in a way that doesn’t mediate it through a U.S.-Americanized idea of Latin American “political poetry.” You make no effort to make Adoum’s complexity more palatable for a U.S. audience. The language is unapologetically the event. Poetry like this from Latin America is mostly untranslated into English (I’m thinking, for example, of José Lezama Lima’s Dador). prepoems breaks new ground, and I have to wonder if you found inspiration in other transgressive, translated englishes. What models did you look to?

KMH: Absolutely, just as any writer, I turned to other writers for inspiration. Pierre Joris’s translations of Paul Celan have been fundamental in the rendering of Adoum into English. I think a reader of Adoum in English can immediately see how Pierre’s embracing of Celan’s neologisms in English is reflected in the translation. But, the inspiration goes far beyond the mechanics of the translation to the poetics of it. Pierre’s notion of nomadic poetics, of how poetry defies borders by its very nature, of how language is always other, of how writing is “the practice of the outside,” has played a major part, too, in my vision for this book and of what it means to be a translator more broadly.

There are, of course, others. I could not attempt to translate Adoum without going to the poet he considered his master: César Vallejo, and studying the translations of his poetry by Clayton Eshleman, Michael Smith, and Valentino Gianuzzi. Vicente Huidobro is essential reading too, particularly Altazor, both in Spanish and in Eliot Weinberger’s English. Friederike Mayröcker through Jonathan Larson and Donna Stonecipher have been important. And then I have my school, which has been to frequently translate two of the most challenging poets in the Spanish language: Juan Gelman and Víctor himself. There are a number of other poet-translators whose work and ideas are always with me: Forrest Gander, Margaret Randall, Don Mee Choi, Johannes Göransson. A group of “emerging” translators I have been fortunate to work with has also had an impact; people like you, Katrine Øgaard Jensen, Paul Cunningham, for instance. And, though I only read him after finishing the Adoum manuscript, I’ve found in Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine (through Conor Bracken, Pierre Joris, and Jake Syersak) a translational kinship.

(And just a quick aside, I wanted to thank you for this question in particular because it rejects simplistic notions of translation being some kind of mechanical exercise and highlights that all writing is a kind of translation, a palimpsest, a spiral of ideas interacting.)

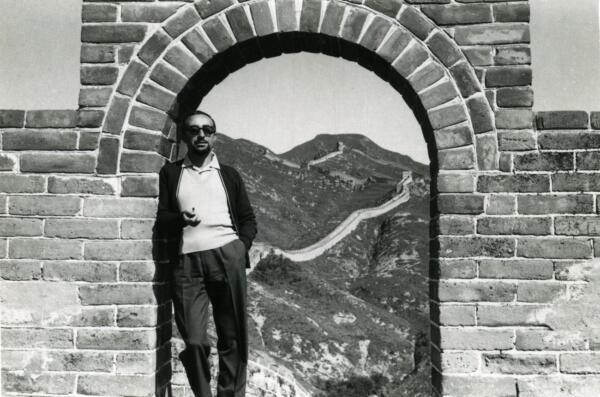

Jorgenrique Adoum

OL: I like the idea of “nomadic poetry,” here, and, particularly, that you evoke it in relation to the work of translators in defying borders—of language, nation, poetics. It makes me think of your discussion of “countermapping” in your translator’s note to Víctor Rodríguez Núñez’s from a red barn (co•im•press, 2020) as another border-defying translational practice. Both of these reroute the hegemony of English through translated englishes out to disrupt capital-E English. All of this seems a fitting space within which to locate prepoems. You write about translation as tergiversation, an act of “[abandoning] any loyalty to the language of neocolonial power for another,” and here you’re quoting Adoum’s poem “Ecuador”, “from an unreal country bordered by itself, split by an imaginary line.” What does it mean to bring Adoum into postenglish at a time when borders are more regulated than ever, and the exclusionary logic of nationalism more reinforced than ever? What are the politics of “postspanish” and “postenglish” in 2021?

KMH: prepoems in postspanish is a timely volume precisely because it addresses the realities we are living at this tumultuous moment in a way that can give us perspective and also hope, I think. You are an expert on the sixties in Latin America. You know it is a crossroads, a re-coming into consciousness, a big, fierce decolonialist fuck you. Adoum’s poetry to me is the best of that: experimental, cerebral, playful, angry, and profoundly transgressive. The political urgency of his poetry is a lesson for us. BUT, it is not just that. It is also profoundly human in the sense that the political urgency tends to begin with the personal, often with romantic love. So many of the poems here are ultimately love poems (“Fait Divers,” “May 1968 (21st Century?),””In the Beginning Was the Word,” ”Hôtel Saint-Jacques,” just to name a few). Love Disinterred, the long poem that ends the book, is his masterpiece in that regard. It reflects upon the “Lovers of Sumpa,” the remains of an embracing Paleo-Indian couple found in Ecuador, as a way to dismantle Western definitions of love and to critique how those definitions limit us. For Adoum, love itself and how we love (romantically and beyond) has the potential to be deeply subversive and I think that is something we need to talk about in more thoughtful ways. It is one of the main reasons I am drawn to his work.

I would also like to add that bringing Adoum’s postspanish into postenglish is only part of the project. Adoum is not as well-known as he should be in the Spanish-speaking world or in academic circles for Latin American literature in the U.S. His work is difficult to find outside of Ecuador. That being the case, this edition rescues Adoum in Spanish as well. It is bilingual and all poems in the original Spanish (or postspanish as the case may be) have been carefully revised by his literary executor, Alejandra Adoum. My explanation above of why this work is so timely holds for both the Spanish and the English, as well as for other languages he may be translated into. Adoum has much to tell all of us.

Jorgenrique Adoum’s prepoems in postspanish and other poems is now available to preorder as part of a special 4 for $40 bundle offer!

Katherine M. Hedeen is a translator, literary critic, and essayist. A specialist in Latin American poetry, she has translated some of the most respected voices from the region. Her publications include book-length collections by Juan Bañuelos, Juan Calzadilla, Juan Gelman, Fayad Jamís, Hugo Mujica, José Emilio Pacheco, Víctor Rodríguez Núñez, and Ida Vitale, among many others. Her work has been a finalist for both the Best Translated Book Award and the National Translation Award. She is a recipient of two NEA Translation grants in the US and a PEN Translates award in the UK. She is a Managing Editor for Action Books and the Poetry in Translation Editor at the Kenyon Review. She resides in Ohio, where she is Professor of Spanish at Kenyon College. More information at: www.katherinemhedeen.com @kmhedeen

Olivia Lott curates Poesía en acción on the Action Books blog. She is the translator of Lucía Estrada’s Katabasis (2020, Eulalia Books), which is longlisted for the PEN Award in Poetry and Translation, and the co-translator of Soleida Ríos’s The Dirty Text (2018, Kenning Editions). She is ABD in Hispanic Studies at Washington University in St. Louis, where she is writing a dissertation on translation, revolution, and 1960s Latin American neo-avant-garde poetics.

Poesía en acción is an Action Books blog feature for Latin American and Spanish poetry in translation and the translator micro-interview series. It was created by Katherine M. Hedeen and is currently curated and edited by Olivia Lott with web editing by Paul Cunningham.