“Don’t ignore what’s sliding down your thighs” (19) the workshop bids, implicating and immediate. Sub Verse Workshop is formed as an Abecedary of trainings with the poet’s ‘I’s. The goal is not to make multiple pronouns cohesive, but to investigate the possibilities of each of these ‘I’s, to see how far they can go amid the flow of gender-fluidity. This is a project emerging from and referring towards performance. The book begs for tactility— taking words off the page and onto skin, voice, room would allow the loud verse to occupy all the spaces it points towards. This is a text full of multiplicities translator Ilana Luna terms “bio-political relations, micro-economies, neo-mythologies, sexual technologies, hybrid esthetics, and elastic concepts” (Luna p.viii). Sub Verse Workshop is an experience of being entirely with, an antidote to this time of grief and separation— a workshop full of aliveness in all of its creative and sexual energy, which does not preclude the plague, the infection and the mutation.

Ilana Luna’s translation is sensual and attuned, centering what Luna terms ‘transcreation’ in the process of making a body of verse new through collaborative iterations of immersion and performance. Luna’s mode as a translator depends upon embodied immersion. Luna described translating Judith Santopietro’s Tiawanaku. Poemas de la Madre Coqa/Poems of the Mother Coqa alongside the author in Mexico over several days of cozy, heady flow. Sub Verse Workshop was trans-created over the course of public performance and long nights of workshopping aloud alongside Huapaya in Phoenix, Arizona, where Luna is Assistant Professor of Latin American Studies at Arizona State University. The workshop is a slithery text that calls out for a work of intuition, evading and defying literal translation. Luna describes the workshop as a text in constant mutation; publication fixes the workshop in time, while at once disseminating it in book-form for further mutation.

Taller Sub Verso was first published in a cardboard chapbook in Paraguay in 2011, followed by editions in Lima in 2011 and Mexico in 2014. It is a workshop that writes against inherited patriarchal culture, conservatism, and the regulation of binaries— “I am a woman for political purposes/ and a medical diagnosis of those who regulate/ the binomial that controls our sphere” (73). Luna describes how translation “breathes new life into the poetry, capturing, too, the spirit of the times in the new language and locus, transposing here the Lima of the early aughts, to a less fixed, more expansive socio-political place” (p.vii). The trans-created workshop takes place in an entirely new context of binaries, Phoenix being a locale afflicted by the racial identity politics of the US-Mexico border. The workshop declares, “you are not national nor international, but spatial and submarine” (43).

The workshop gives the sensation of a gathering, a festival, an intimate orchestration of “the symphonic tongue” (29). This happens in second person plural directives and colliding aesthetics. Huapaya is former director of the Festival de Poesía de Lima/ Lima Poetry Festival, and a curator of visual poetry through PirúBirúPerú. Huapaya describes, “I am interested in languages — and the poetics — that result from a communion. I am interested in their political flow and their development as resistance to the hegemonic, their capacity for permanent reinvention through the inclusion of the remembered / the spontaneous/ the altered / the risky” (Jacket2). The translation of Taller Sub Verso comes out in a world of new curations, while the practice of orchestrating languages of communion continues as a through-line in Huapaya’s literary leadership between Latin America and the US. A founding editor of Cardboard House Press, Huapaya is now dedicated to “designing a coherent catalog of what we consider to be the most innovative poetics from Spanish and Hispano-American panoramas” (Jacket2). These projects of curation and hosting feed and extend the spirit of the book.

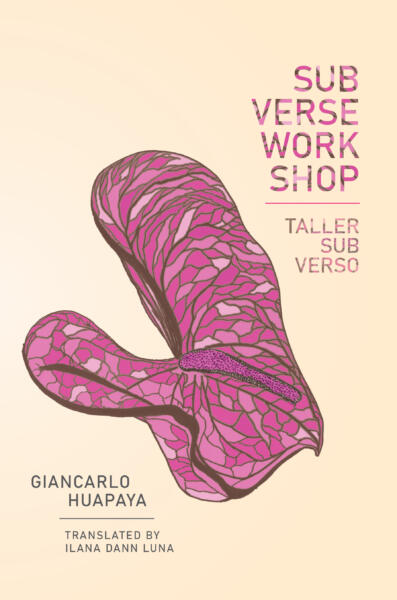

The sensuous lily image on the book cover by artist Janine Soenens, re-touched from previous editions of Taller Sub Verso, is a form at once concave and convex, well and point. “Conviértanse en un embudo”(18), “become a funnel”(19) the workshop instructs. The funnel recurs in Huapaya’s work as another form that gives and receives, orifice and protrusion. A funnel was the cover image of the art journal Lapsus Collage Editorial, which Huapaya directed in Lima, and which uniquely published criticism on post-porn as aesthetic movement. The funnel is a potent symbol for this workshop. We know the ‘I’ insofar as we know what it gives and receives; what it shares and withholds— “I’ll lend you my perineum” (23); “in each rusted song my moan will beg from within your pores.” (45). The ‘I’ becomes seen by how it is encountered outside of itself, until “what’s mine will be eliminated from what’s mine” (57).

Insofar as beings occupy multiple roles in this workshop, there is no set delimitation between ‘author,’ ‘translator,’ and ‘reader.’ “The roles of the workshop they intertwine/ they kiss/ they drool because we’ll all pass through the polyphonic milk”(81). This intertwining applies too to the role of translator. “Take off your orifices and throw them like dice” (71) the workshop suggests, detaching orifice from expectations of gender or behavior. As orifices are thrown into the air, so too are expectations on who is host and guest within the text. Words cross over between the Spanish and English; “The citizenry is bombarded by caca” (89), “Flashing exaltará la proporción aurífera de los órganos” (70). At times, the translation slithers into the flow of new rhythms and assonances, “That S will traverse the vowels of your howls, the velvets” (79). At other moments, Luna makes apparent the spaces crossed in translation. For example, the workshop moves between second person singular and plural and Luna is left to cue English readers into multiplicity in different ways. At times this is through the straightforward if less common phrasing ‘you all.’ Other times, fascinating solutions widen the way for reading further multiplicity within the individual. For example, “come back from the more festive side of your torsos” (19). The plural ‘torsos’ effectively and curiously encompasses the possibilities of internal as well as external multiplicity in an embodied way.

Throughout, the workshop interrogates how reproduction happens; “In the depths we’ll sow our DNAs so the moon can fertilize genomes” (54). This interrogation of reproduction includes upending the supposed reproduction of translation. Luna describes the style as “fragmentary and brutal”(p.viii). But amidst this, there is also the abundant tenderness of witnessing a speaker instructing themselves. As readers, we have an ear pressed against a translation that happens within an individual in internal attempts towards understanding. “Your little body bangs against the metal grating. Feel the multitude of adolescent damages” (41). Many poems have a sweaty, hormonal feeling of pubescent discernment; adolescent recalls adolorido: in pain; the pain of growth. These moments have a spirit of auto-translation, insofar as the ‘I’ is what is continually reproduced; “like a liturgical choir, compose with a computer according to your metempsychosis and transfer your heritable characteristics to me” (19). The ‘I’ itself emerges from reproductions.

These reproductions are consistently in defiance of the body in capitalist production, trained in mechanistic functioning. ‘Workshop’ itself recalls sites of production (even more fervently than the Spanish ‘taller’ from the French atelier, site for fine arts), but this workshop is a site of improvisation and a training in desire. In reading Taller Sub Verso, Paul Guillén quotes Slavoj Zizek in The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema, “Hay que enseñarnos a desear.” “Ilustren sus distracciones” (28) Taller asks. Luna’s translation, “Make your amusements known” (29) resonates with an opening question of Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts, “What’s your pleasure?”

In this workshop, “the reader is sexualized space and will stop putting themself in the position of one who doesn’t know” (79). Huapaya’s earlier title Polisexual plays with the sexual ‘polis,’ the territory across which capitalism constructs and suppresses sexual categories, and the poetics which might expose these fissures. In both books, the body is approached as terrain, in the sense that Cristina Rivera Garza frames territory as space plus politics. The publication of the translation of Taller Sub Verso brings out connections with Huapaya’s latest project in process, GAME[R]OVER, which focuses on geographic and virtual terrains of late capitalism and xenophobia, centering on Phoenix, AZ. At a reading with translator Ryan Greene at San Francisco State University, GAME[R]OVER declares, “Tu cuerpo es un movimiento financiero,” “Your body is transaction.” These are themes imbued through Huapaya’s own work as a translator, most recently of Susan Briante’s The Market Wonders and Defacing the Monument, as well as of the work of Carmen Giménez Smith, Muriel Rukeyser, and Alli Warren.

Commitment to creating alternate spaces that subvert capitalist centers of production is a through-line in Huapaya’s projects which surround Sub Verse Workshop. As a performance artist in Lima, Huapaya worked with micro-territories: putting spaces in crisis through performance, and inscribing new possibilities into spaces through the memory of that experience. Although now in a wildly different context, Huapaya’s collaborative leadership organizing bilingual bookmaking workshops through Cardboard House Press’ Cartonera Collective is yet another iteration of the creation of tangible spaces which center transparency in processes of production, collective creation and pleasure. A workshop participant reflected, “I realized that I didn’t know the stories behind all the hands that were working to make books that told other stories” (Felix Castro, Tripwire Cartonera Collective Pamphlet, p.36). Sub Verse Workshop is another site of discerning the stories behind the bodies that tell other stories.

The workshop houses elements of essayistic argumentation as it tries out pronouns and peels through layers of internal subjectivity. The body is not absolute or given, but rather a being in constant construction and ruin, only ever expressed in fragmented form. One aesthetic moves suddenly and sometimes violently to another aesthetic, as the workshop moves around and within the internal and external multiplicity of the ‘you’ it addresses. This is a workshop for the dissident body defying corporal control. It isn’t so much about gender as it is about wideness—about what we, individually and as a collectivity—can contain.

References:

Marci Vogel, ‘Languages of communion: in conversation with Cardboard House Press’ Giancarlo Huapaya’ Jacket2 <https://jacket2.org/commentary/languages-communion-conversation-cardboard-house-press-giancarlo-huapaya>

Paul Guillén, ‘Contemplación en caos y disidencia: El proyecto poético de Giancarlo Huapaya’ <http://letras.mysite.com/pgui230614.html>

Cartonera Collective, cardboard minutes // libro de caja <https://tripwirejournal.com/2019/11/13/two-new-tripwire-pamphlets-antena-cartonera-collective/>