Paul Cunningham: When did you first begin translating Josué Guébo’s poetry? What drew you to his work?

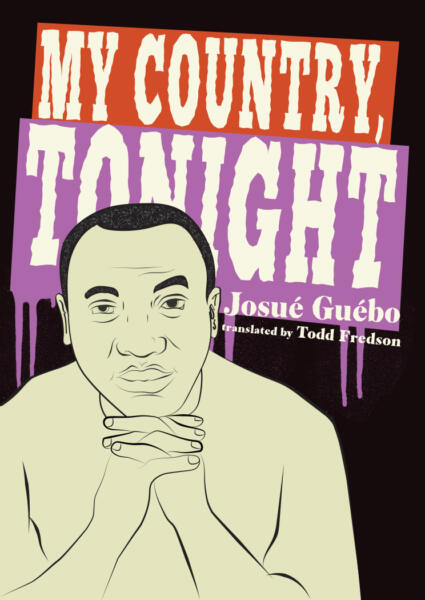

Todd Fredson: I was drawn to Guébo’s poetry because of his subject matter, initially. I was researching the literary responses to the ethnic and political violence of the first decade of the new millennium in Côte d’Ivoire. I’d lived there for two+ years as the first civil war took shape and was wrestling with that experience—and with the ethics of representing it—in my own poetry. I wondered, of course, how Ivorian poets were creating expressions for their experiences. I started looking online and was really excited about the poetry that I found—this was in about 2013, and Guébo’s book Mon pays, ce soir / My country, tonight had come out in 2011. He was, at that time, the President of the Writers’ Association of Côte d’Ivoire, so he was easy to find, and he was speaking about the misrepresentation of the conflict by the international media which reduced it to localized ethnic and religious violence. However, that violence is the trickle down effect of Western economic policies, he said. My country, tonight calls out the direct military interventions by the French and the UN and the West’s dismissal of Côte d’Ivoire’s sovereignty following the 2010 presidential election. The collection calls out the history and consequences of such neocolonialism—in Côte d’Ivoire and more widely in Africa. His tone is probably what compelled me to actually translate the work. I love how incisive and direct his speech is, even while he is creating these surrealist allegories that match the absurdity of the West’s interventionist rationale—its language of aid and humanitarianism that is, of course, militantly carried out. The poetry is elegant and relentless and full of dark humor. I started emailing him and he supported my translation of the book, and we’ve continued working together.

PC: What challenges did you face translating Guébo’s My country, tonight? Is there a particular passage from My country, tonight you’re most proud of?

TF: One of the challenges is working with the vernaculars and language play in My country, tonight. While Guébo doen’t directly use nouchi, which is a kind of common tongue in Côte d’Ivoire—I think calling it a pidgin would be inaccurate as it’s not a simplified form of anything, it is a hybridized language of its own, really, made of ethnic languages, French, onomotapieas, and the like—while he doesn’t use this directly, Guébo uses “Ivoirismes,” which are idioms in French that are specific to an Ivorian context and would not be legible in continental French. Nouchi and Guébo’s first language, Dida, sort of always haunt the colonial language—there is a resentment toward the French language in his work. Like many Afro-francophone writers, Guébo is interested in busting up the French language, which is an abstract system of governance complicit with the economic oversight of neocolonialism and neoliberalism. Guébo is crafty with his language.

So, for a passage that I’m proud of or would point to here is one where Guébo portrays the UN as a snaking, sexually predatory water. He uses the term l’eau nue, which translates literally as “bare water” or “naked water” but also has the homonymic association to O.N.U., which is the acronym for Organisation des Nations Unies—or, in English, the UN. That’s what’s going on in the following passage:

L’eau nue

Plotting its course

Far from the suffering

Of my people

L’eau nue

Gliding into

Its guest bed

Pic-

Nicking

Or rather playing

Snatch

Grab

Along sidewalks (Guébo, My country, tonight, 2016, p. 17).

I like the “Snatch / Grab” phrasing, particularly. It’s hard to translate word play. The original reads “Ou plutôt / Piquant / Et niquant”—“Or rather/Or more like… .” “Piquant” literally means “spicy” or “being poky or pointy” but can have several associations such as being acerbic or caustic. It has several slang associations from the verb “piquer,” including “jabbing,” “getting hooked on or addicted to something,” “pinching or filching,” “nabbing or collaring.” The word “niquant” means “to screw someone over” or, more to the point, “to fuck someone” in a sexual sense.

In the translation, “Or rather playing / Snatch / Grab,” the phrase “snatch grab” maintains the coarse vernacular. “Snatch” is vulgar slang for vagina, so the phrase follows Guébo’s portrayal of the UN as an assaulter, someone who will just “grab ‘em by the pussy” as Donald Trump would clarify shortly after the translation came out. But “Snatch and Grab” is also a military crowd control tactic, and the police in NY had used it against Occupy Wall Street protesters. The police surveil the crowds for people who are organizers and leaders, then the police form a diamond-shaped wedge, inserting themselves into the crowd, and they pummel and drag those “dominant agitators” out. It’s a tactic that’s continued amid the many Black Lives Matter and other domestic protests. Having that military violence resonate within the language of sexual assault felt like the right translation, given Guébo’s characterization of the UN interventionists.

PC: In your translator’s note, you write, “By translating this collection I am hoping to bring into view the contingency of local conditions that are often glossed over when ‘Africa’ gets included in discussions of capital and precarity.” Can translation be viewed as a gesture of decolonization?

TF: I don’t know.

In my more optimistic moments, I think translation can decolonize American readers and the English language a bit. It can bring new expressions and new textures of language into the forum. It can provide a fuller historic perspective for those trained into the narratives of American or Western Exceptionalism. Maybe American readers and those in the purchasing class can begin to have a sense of what their consumer choices mean for those living in producing nations or the Global South and what has gone into making those consumer choices available.

But also I feel like I am just a dog chasing its tail. I am an American intellectual confronting history and cleaning up ledgers while the systems of oppression I am criticizing are being constantly updated to take on new forms. I’m looking around or back to confront previous systems while beneath my feet the new systems emerge—our structures of exchange or population management are already post-national, post-regulated, post-real, etc. I move inch by inch, and in that time it takes to expose and shed light, the powers-that-be have already again shifted things, have moved the goal posts, have guarded their powers with new misdirections.

In a 2014 interview for the Harriet blog, Juan Felipe Herrera reflects on the difference that is emerging between culture created by algorithms/analytics/surveillance and the interpersonal human culture. “We can entertain ourselves with writing,” says Herrera, “and it’s very powerful, but something else is going on and I don’t know if we know how to deal with it in our writing. Or if it can be dealt with in our writing.”

He points to this amorphous meta-structure that seems to float in relation, like a magnet repulsed by another, sliding around, always discovering the empty or most vulnerable space, whatever territory opens up when our attention shifts, when our eye moves away—and it colonizes that space. It exploits from there.

Lauren Berlant has a section in Cruel Optimism when she is reading a John Ashbery poem and considering the speaker’s moment of suspension, a lyric or episodic interruption, that offers the possibility of “imagining a radically resensualized post-neoliberal subject.” Without being able to extend that moment, though, there is still nothing but possibility because “this is not an event but an episode in an environment that can well absorb and even sanction a little spontaneous leisure” (p. 36). I feel like this, too. With most American academics or intellectuals I am operating in an environment that sanctions and absorbs my episodes.

I don’t know if translation is an act of decolonization. Hopefully, widening what’s available in English offers inspiration, breaks some people’s sense of isolation, and can build unity—massive, bulk solidarity, eventually, even.

PC: Do you have any new projects in the works?

TF: A project that I edited, a microanthology of contemporary Ivorian poetry in translation, just went up at Jacket2.

A translation of Tanella Boni’s most recent collection Là où il fait si clair en moi / There where it’s so bright in me, which won the 2018 Prix Théophile Gautier from the French Academy, is forthcoming from University of Nebraska Press.

And I’m getting to the end of a translation of a long/booklength poem from Azo Vauguy. It’s an extension of his previous collection, Zakwato, so that my Country never sleeps again, which is also a long/booklength poem. Zakwato is a myth Vauguy’s taken from from his ethnic background—it’s a Bété myth that he’s taken from its oral keeping and put into French. I’ve got a critical essay about the complex socio-political environment into which the poem emerged, and to which he was responding, that finally emerged from the peer review process in an academic journal. So now—and this is an eight year project at this point—I have the original French version of Zakwato along with a translation, and a critical essay to help understand the uniqueness of the long poem and its cultural significance, as well as the original of the sequel, Péril Loglêdou, Voyage to the country of lost sight, and its translation. I’m going to try to find a home for that project soon.

PC: Who are you currently reading?

TF: I’m reading Changes, a love story by Ama Ata Aidoo and Third-Millennium Heart by Ursula Andkjær Olsen, translated by Katrine Øgaard Jensen, which is one of the many amazing offerings in your Action Books catalog! I’m also re-reading Danielle Pafunda’s collection, Spite.

PC: What advice would you give to emerging translators?

TF: Know writing across genres and styles, beyond whatever your own preferences are. Recognize your aesthetic defaults so that you don’t create a personal overlay on all of your projects—any more than happens anyway. Know literary histories—the lineages of writers you translate, the different literary movements that have influenced them, the socio-political conditions across those times and out of which the text has emerged. But, if you’re reading international literature and translating then you’re probably already off to a great start.

Todd Fredson is the author of two poetry collections, Century Worm (New Issues Press, 2018) and The Crucifix-Blocks (Tebot Bach, 2012). He has made French to English translations of Ivorian poet Josué Guébo’s books Think of Lampedusa (University of Nebraska Press, 2017) and My country, tonight (Action Books, 2016), as well as Ivorian poet Tanella Boni’s collection The Future Has an Appointment with the Dawn (University of Nebraska Press, 2018), which was a finalist for the 2019 Best Translated Book Award in poetry and the 2019 National Translation Award. His translation of Boni’s most recent collection, There where it’s so bright in me, is forthcoming (University of Nebraska Press). Fredson’s poetry, translations, nonfiction, and criticism appear in American Poetry Review, Boston Review, Warscapes, Jacket2, Research in African Literatures, and elsewhere. He is the recipient of Fulbright and NEA fellowships.