Adriana X. Jacobs: I want to start with a question about the title. Even readers who don’t read Russian may note that there is a difference here between the Russian and English. An early working translation of the title was “Awesome,” which is so disarmingly informal. At what point did you change the title to Letters to Robot Werther and why?

Rachael Daum: Working out a good title in the English translation was one of the tougher challenges that this piece gave me. The Russian title is «Зашибись!» which, when I first saw it, made me internally groan at trying to find a good English rendition. «Зашибись!» (pronounced in English as zasheebees!, emphasis on the last syllable) is a wonderful Russian expression that can be used for almost any scenario: did you just win some money at the lottery? You’ll punch the air and exclaim, «Зашибись!» Did you miss the last step and nearly fall down the staircase? «Зашибись!» again. The train doors closed in your face? You guessed it. It can be translated, based on context, as “Awesome!” “Damn!” “Fuck it!” along with a myriad other expressions. The working titles I had along the way varied greatly, starting with “Oh, Great!” (hoping for the irony to do some heavy lifting) and going to “Awesome!”, which as you say is alarmingly informal, and I even considered “Hunky-dory” for a bit. Nothing really felt right.

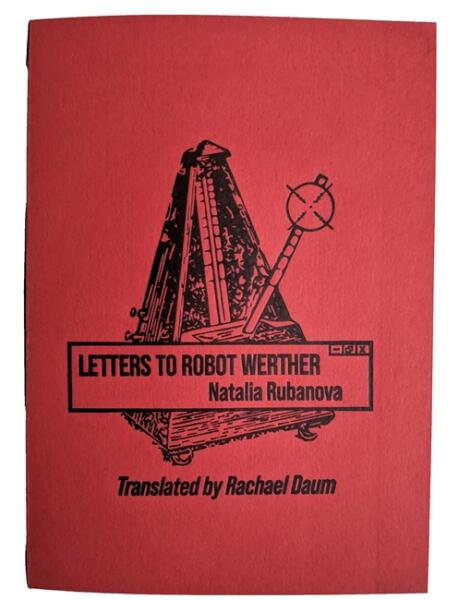

Anton Hur discusses the titling of his translation of Sang Young Park’s Love in the Big City, and he points out that there’s something lovely about being able to push for a different title in translation from the original, to signal that the translation is a different text entirely, to distance the book from the source. This asserts the work as its own creation, and I really like that take. Marian Schwartz also has a great piece on how the titles of several of her translations of Nina Berberova’s works came to be, sometimes out of necessity to capture the register or the onomatopoeia that sparked the original title. In my case, I just couldn’t find a phrase that we can use as ubiquitously in English as the Russian title (which also, I’d like to point out, contains the Russian word to beat in it, suggesting the violence to come within itself), so there was a point where I just needed to step away from that idea altogether. It was surprisingly late in the process—it was a decision I’d been putting off till the very end—and in stepping back to look at the piece as a whole, I thought something that would honestly just be more interesting is to present the structure of the work within the title. I also liked the idea of taking advantage of the fact that emails can be called “electronic letters” in Russian to set an analog communication form—letters—against a futuristic figure that has roots in a pre-electronic-technologic world—Werther—to create a dissonance that will hopefully spark intrigue in an English reader. I’m grateful to Natalia for her trust and her openness to changing the title in translation. When I suggested Letters to Robot Werther to her, she asked, “Well, is it interesting? ” I certainly hope it is.

AXJ: You describe this translation as “slightly side-stepped” which is such an evocative description of the non-linear relation between original and translation. But you also follow this with a chess reference, suggesting that there is a translation strategy at work even if the reader doesn’t always see how you are moving across the text/board. How conscious is this side-stepping for you as a translator? Is it present from the beginning or a kind of movement that you can enact at a later stage in the translation process?

RD: I really love a chess metaphor (and I admit the knight’s-leap image is one from a short story by Nabokov that has always stuck with me), though I’m too impatient to be much of a chess player myself. Translation is a game I prefer to play, as, at least at first, it’s just me playing against myself and figuring out how the pieces best line up. As far as a strategy goes, when I am first reading the text there are moments where I look at the text and think, “Ah, I’ll translate it like X or Y,” but the strategy actually starts when I actually begin digging into the text: as the English starts forming, the strategy will, too. With this text in particular, because Natalia’s Russian is just so odd, I decided to let myself side-step a bit further than I would normally. So much of her work is sound- and play-driven, so that I felt that I could allow myself, for the sake of rhythm or the music of the text, to let a note play out further in the English, or lean into a pun that the English allowed for.

AXJ: This is a translation that is meant to be staged but also includes visual puns, underlined phrases, words with extra spaces between the letters. Are these elements meant to be performed and to what extent were you thinking about their performance, and performance in general, when you were translating this book? Did the idea that this could be performed inform your translation choices in any way and how?

RD: I was really glad to get to take part in the first theater strand offered at the British Centre for Literary Translation (BCLT) summer workshop in summer 2020, where I could ask this precise question! I’m not an actor: I have translated drama before, but never have I translated drama that has so many page-based factors, things that won’t transfer onto the stage. These text-based jokes and elements are a staple of Natalia’s writing, and so it is natural they are here too, but what does that mean for the stage? Generally, what those elements do is to inform the tempo of the sentence, the emphasis, the weirdness. When I asked this question, I was generally told: yes, that’s odd, but the actors will figure it out. I felt comfortable leaving them as they were to inform a potential actor of the oddness of a line, while giving them the space to enact it how they would like. I rather like these elements being left on the page: they feel like a wink to the reader and to the actor who knows the page, almost an inside joke. There are Cyrillic letters in this word, but the audience doesn’t know! Shh!

The idea of this being performed someday did very much influence my translation. I have had a section of a play I translated performed as a staged reading, and it was one of the best experiences I’ve ever had as a translator (the jokes worked!). A big portion of this translation was spent reading parts aloud, to find out how speakable they were while also, when possible, staying close to Russian sounds (there’s the scorch example near the start of the play). There is also a staged reading of the original Russian available on YouTube which also helped as I was translating to find performative rhythm and sound.

AXJ: I was curious about the inclusion of lines from Goethe’s Faust and the relation between German, Russian, and English in these moments. Is NR translating these herself or using existing Russian translations? And if the latter, is the choice of translation meaningful somehow? Are you then translating these references into English, or did you work directly from the German? And how do you make that decision generally when translating already translated material?

RD: This was a part of the play that I found especially gratifying. I love that this piece speaks in conversation with Goethe across his two of his most famous works, Die Leiden des jungen Werthers and Faust, and bringing them into a useful, modern conversation. The lines lifted from Faust are Gretchen’s song as she sits at the spinning wheel, pining for Faust, and that the nameless narrator of Rubanova’s work sings these words with her voice is in itself a fascinating turn! Having the three languages in conversation is, for me, a really beautiful intersection. The Russian translation that Natalia employs here is Russian Soviet poet and novelist Boris Pasternak’s translation; his translations are, to my understanding, the most popular in Russia, so choosing his translation was perhaps the obvious choice. (But when in doubt, why not choose the translations done by the author of Doctor Zhivago, after all?)

As to my translations of these lines, I also translate from German, so I opted to work directly from the German for this song. The exception here is to the last few lines, which appear to be additions from Pasternak in his translation: Goethe’s song ends:

Und küssen ihn

So wie ich wollt’,

An seinen Küssen

Vergehen sollt’!”

(And to have kissed him / as I wished / and to have perished / at his kiss!) But Pasternak’s ends:

Я б все позабыла с ним наедине,

Хотя б это было,

Хотя б это было,

Хотя б это было погибелью мне,

Хотя б это было погибелью мне.

Which, even if you don’t read Russian, you can see it is a whole different form! So I opted to translate that section directly from Pasternak as, “I would have forgotten everything with him alone, / though it would have been / though it would have been / though it would have been my ruin, / though it would have been my ruin.” There are extant and excellent translations into English of Goethe’s Faust, but because of the interaction with Pasternak’s translation, I opted to do it all myself, since in this instance I was able to do so. (And, selfishly, I like the idea of being in a direct translation conversation with Boris Pasternak!)

AXJ: The correlation that you draw in your introduction between the Russian Superfluous Man and incel culture demonstrates very persuasively how translation, in your words, can open a work to “new activist contexts.” But were there moments when you needed space from this protagonist? And if so, how did you find your way back to the translation?

RD: Thank you for saying so! That creative aspect of this translation is one of the most exciting parts of it—I think both for Natalia and for me. It certainly sparked an interesting cultural conversation between us that I don’t think we would have had otherwise.

Turning to the narrator himself: regardless if he is a superfluous man or an incel, he’s really exhausting. When I first read the piece, I did find that I needed to take breaks—until I realized that he wasn’t going to get away with what he was saying. When I finished reading it the first time, there was a feeling of relief, and almost of sadness. I like that he isn’t redeemed (which is very Faustian of him), but on an empathic level, that’s a complicated feeling to have. I did find that my relationship with him changed as I translated him, and by the time I was going through line edits, I could laugh at him, roll my eyes, and say, “Oh, just go to therapy already.” This isn’t to lessen the harmful and frankly gross things he says, but I found that becoming so close to his words was the route to actually distance myself from their effects.

AXJ: You ask: “can a Russian dissonance work in English?” I think you show us that it can, for example in the playful but also awkward relation between “ratio” and “borsch.” But for this to work and feel “purposeful” you have to make English dissonant. How did translating this book change your own relation to English, your own writing in English?

RD: I think translating this book changed my translation and writing process itself a bit, if only environmentally. Normally I don’t listen to music while I translate or write (I suffer from pretty severe tinnitus in both ears), but I made an exception for this work: because Natalia is classically musically trained, it made sense to lean into the musicality / nonmusicality of the piece as a kind of immersion. The music I came across to translate this to was Shostakovich’s eleventh symphony entitled “The Year 1905,” which not only includes a really powerful, dark series, but is capped by Shostakovich’s jocular jazz suites. This seeming disconnect in the music really helped with this translation, which is itself filled with quite dark material, but takes humorous turns: allowing those moods to coexist, accepting them without necessarily interrogating the why of them (at least during the act of translation itself) was really useful.

Shortly after I finished a solid draft of this work, I turned to producing some of my own poetry, and ended up writing a whole cycle of poems centered around Baba Yaga and Persephone. I don’t think I could have done that before translating this work: it opened me up to not forcing two notes/words to chime together, but to allow them to clash, and then to follow that dissonance down the page. This resulted in much more interesting texts, I think, than I would have encountered before translating Natalia’s work. Natalia’s texts play so much with tempo and with sound, so that for the first time I felt like I could do something similar in my own work after, so to speak, wearing Natalia’s poetry coat for a while.

AXJ: In her work on scriptworlds, Sowon Park highlights shifts in power and cultural capital in the translation from one script to another. As a translator from Hebrew to English, I was thinking about this as I read your translation and encountering words like “кuntlickeяs.” How do you perceive the shift between the Roman and Cyrillic scriptworlds and how does it differ when it is Roman alphabet absorbing Cyrillic and not the other way around?

RD: A quote of Park’s from her essay on “Transnational Scriptworlds” that I really like here is, “…the problem that the sound of speech cannot be carried over to another language is not so much the limit of translation as something inherent in the nature of writing systems.” The reason I like it is because it seems to be the root of Natalia’s English-play within Russian, weirding the text: an early example of this in the text is her putting the English word “you” instead of the Russian letter “ю”, which makes the same sound, within a word: her playing between these scriptworlds is, indeed, rooted in the sounds the words make in different languages, because a Russian reader with even almost no grasp of the English language will know the sounds these letters make due how ubiquitous (and fashionable) English-language words and letters are—we don’t need to delve too deep into United Statesian neocolonialism to uncover why. Her pointing out that Russian and English have the same sound transcribed differently makes the joke work elegantly, and indeed the first time I saw it I laughed and thought, “Why didn’t I think of that?”

Conversely, as a translator I cannot expect English-language readers to know Russian words: it is not an equal exchange when language is exported. Whereas Natalia’s use of English to pun the Russian text can be both sound- and sight-based, the reverse cannot be the same of the English text. My experience is that when Cyrillic letters are put into English words, it’s usually for comedic effect: the fact that these letters do not correspond to their Russian phonemes is part of the joke. (I’m thinking in particular here of the 2006 film Borat, the title of which is transcribed with the Russian letter “д” [d] in place of an “a”.) Usually, I eschew that sort of script-based joke (I’ve seen many a Slavicist roll their eyes at it, and it also tends to give readers of both scripts a headache), but here I found it really appropriate: though the tonal aspect drops away, I like the idea of our narrator falling into this scriptworld and contributing to it by weirding his own text. Another quote of Park’s I like (from her biography page) is, “Once a script is learned, it can’t be unlearned. Literacy turns shapes into codes.” This codifying of language—and jokes—within script is something I feel is aptly at work here, and it allows for this playfulness within translation.

Adriana X. Jacobs is associate professor of modern Hebrew literature at the University of Oxford and author of Strange Cocktail: Translation and the Making of Modern Hebrew Poetry (University of Michigan, 2018). Her translations of contemporary Hebrew poetry include Vaan Nguyen’s The Truffle Eye (2021, Zephyr Press). She is currently translating Tahel Frosh’s Avarice with the support of a NEA Translation Grant. Find her @ladymacabea