curated by Katherine M. Hedeen

Reviewing poetry in translation

- recognizes translators as authors

- destabilizes narrow definitions of originality, authenticity, and authorship

- makes visible the artistry of translation

- is dissent, defiance, disobedience, subversion, solidarity

Where better than the Action Books blog to do the work?

Microreviews of poetry in translation coming at you every few months right here!

Luis Chaves. Equestrian Monuments.

Luis Chaves. Equestrian Monuments.

Trans. by Julia Guez and Samantha Zighelboim.

After Hours Editions. 2021.

70 pages. $18.00.

“Underneath all of this there’s a song / even if it can’t be seen or heard” A gallop, or leap, or trot—muted, paused. Like the sculpted horse-body of any equestrian monument—suspended between past and future—these poems will leave spectators desiring and re-imagining concepts of movement. Thoughtfully co-translated by Julia Guez and Samantha Zighelboim, Luis Chaves’s Equestrian Monuments can be approached as a genre-defying guide to the suspension of motion, or the author’s own motion to suspend the rules of poetry. Considered one of Costa Rica’s most acclaimed poets, Chaves’ English-language debut features deliberately slow-paced ruminations on aging, recurring out-of-focus photographs, and the plasticine build-up of an anxious brain. The author recognizes plastic as both a pollutant (“things that’ll never biodegrade”) and the color of that which does not exist (“the color plasticine bars make”). The plasticine, in both a physical and lyrical capacity, is what contaminates both our natural environment and our senses. Equestrian Monuments offers a poetry of slow-motion and deep time.

To access the many layers of Chaves’ underlying song, we cannot rely on sound alone. The title poem swells with sweeping “fog” and “out-of-focus photographs,” casting a shadow on the poet’s younger self and questions of identity (i.e. his mother’s constant fascination with his sexual orientation). Chaves’ “fog” becomes a metaphor for anxiety medication that doesn’t appear to adequately reduce the speaker’s anxiety. Concerned with time, mortality (“the park’s elderly, unmoving”), and identity (“when drag queens begin / to grow beards”) accumulate in uncanny and transformative ways:

flattering the silhouettes

of the park’s elderly, unmoving.This is how it is or this is how I see it through

the extenuating filterof 10 mg of Klonopin.

**

The fog of the drug,

low-impact anecdotes,

scenes from badly dubbed films.At that hour of the morning

when drag queens begin

to grow bears.

Later, in “False Fiction,” the speaker presents shadows in a more positive light, citing “good” shadows:

I am followed

by my daughter, the cat and the dog.

They are my good shadows.

Throughout Equestrian Monuments the invisible sound of the past forms a vibrating inventory of years and weeds, ache and wisdom. Chaves brings everything outside in. This happens in the beginning (“Clothes out to dry / and those clouds”) and in the end (“The outside world seems to flow with naturalness and calm. I want the inside world that way too”). This poet’s limitless inventory of external forces prompts the reader to pause and become something else entirely. (PC)

Jeannette L. Clariond. Goddesses of Water.

Trans. Samantha Schnee.

World Poetry Books, 2022.

215 pages. $20.

In this spectral lyric of interconnected beings, Jeannette L. Clariond’s Goddesses of Water and Samantha Schnee’s translation honors the intimate interstices of life and death through surprising echoic diction. From Spanish into English and, significantly, from the voices of the disappeared to the ears of the living, Clariond calls on readers to “Listen to them: the fluttering of a hummingbird at the first light of dawn.” It is an invocation to consider a universe in which no form of existence is truly severed from another.

The collection begins in “ur-darkness,” a liminal space from which creation is abundantly possible. The goddesses of water, like many Mexican victims of femicide, are essential laborers whose contribution is integral to the land’s richness. The goddesses resist their disappearance by cultivating landscapes that are also lyric-scapes. The goddesses and their “daughters” are “masters of their own desire” who, through their free will and creativeness, are not ruined but spatially rearranged sources of fertility: water, seed, blood, and poetry. The synthesis between humankind, flora, fauna, and celestial bodies is braided through the careful tension of invention and receptivity, as a goose in a lake, too, becomes a daughter of the Moon and “deciphers its destiny.”

A site of resistance is proclaimed when the speaker recounts, and so testifies to, the story of the Moon’s cycles of revival after she is slain by her brother the Sun. Likewise, the Nahautl words, which illuminate Aztec mythology in this collection, defy translation altogether; instead they are rooted in context within the text’s meditations. The speaker reveals herself in increasingly stark moments where “we,” “us,” and “I” emerges to deliver stinging inquiries—“Where will their light go without the refuge of history?”—and declarations—“The hair on your chest//understands my tears/better than your heart.” By speaking the unspoken she, like the Moon, is both “woman and mirror” gathering “that which dispels horror.” Here, poetry is a pool of complex reflection exposing the cosmic imbalance of injustice that continues to claim thousands of poor, trans, and indigenous women’s lives. Here, too, “wings of contradiction made no one’s dreams fade.”

As a reader of Clariond’s exquisitely-bound poetry, I found myself drawn to its boundlessness. Its concentration on the relationship between infinite earthly, human, and celestial transformation defies the arbitrary limits of borders, bodies, and even time which “bleeds, too.” Notably, the choice to place Spanish and English text alongside each other creates a mirroring affect. Likewise, the shape of descent and fragmentation, and the inference of diaspora and migration, materializes on the page. As lines grow smaller or more scattered and seem to fall into or arise from fecund darkness, indeed “Their essence dwelt in the Afterlife. Their petals arose in song.”

In a devastating postcanto, the now prosaic verse becomes a looming proclamation that alights from among the slaughtered. As “the silence of these bodies resounds throughout this barren land,” we are implored to return to that initial call to urgency and free will, and to “listen to them.” (CC)

Jacques Darras. John Scotus Eriugena at Laon and Other Poems.

Jacques Darras. John Scotus Eriugena at Laon and Other Poems.

Trans. by Richard Sieburth.

World Poetry Books, 2022.

$20.00.

Jacques Darras is a translator of British and American poets such as Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, William Shakespeare, and Basil Bunting, among others. He is also known for his multi volume-spanning epic poem La Maye, titled after the coastal river in Picardy, Northern France. For a poet of his literary magnitude, it is remarkable that Richard Sieburth’s translation represents the first significant presentation of Darras’ work in the English language. Not a moment too soon. John Scotus Eriugena at Laon and Other Poems encapsulates Darras’ riverine imagination that underlies his probing philosophical engagement with France’s landscapes and medieval figures. In the sequence, “Forest Ways,” for example, the sparsely punctuated poems magnetise the intimacies of youthful memory that collapse both depth and space together:

beeches being so tall so proximate

to the sky as to eliminate every fringe of light

from their environment yet filtering it through

the canopy at the convergence of their branches (9)

Light’s materiality is a familiar motif, one that circulates the elemental longing for fluidic ecologies as in the poem “Sea Choirs of the Maye: “I love the light on the hump of the sea when the sea turns green / when the sea does its best to take on the color of light” (71). Here light is multi-dimensional: it shapes one’s perception and brings clarity, while its density tenders reflection on the nature of matter and water as in the epistle “To Augustine: On Paradise”:

What is less visible than the water of time? Water thwarts light, unable to seize transparency

in all its layerings and yet I know of no body more luminously alive than water. (91)

Light is but one aspect in this rich collection, where medieval and pagan figures, rivers, trees, and troubadours encounter a variety of poetic forms. The poems themselves resonate with the rhythms of Sieburth’s attentive translations: “by day we are smattered by light / by night we are charcoaled by light / our solar bodies are toasted by light” (26–27). No doubt, Sieburth’s translations reflect Darras’ particular sonic ecologies. The result is a resplendent collection that I hope will enthral new audiences with the vision of this significant French poet. (OT)

Rodolfo Hinostroza. Contra Natura.

Rodolfo Hinostroza. Contra Natura.

Trans. by Anthony Seidman.

Cardboard House Press, 2022.

124 pages. $18.00

Rodolfo Hinostroza’s (Peru, 1941-2016) Contra Natura opens with a chess move: “P4AR.” The chess website iChess.net lauds the poem’s title, “King’s Gambit,” the “most aggressive chess opening”: “your pieces fly out, pawns rage forward, you sacrifice with wild abandon.” The opener has a famed history, used in what’s referred to as the “Immortal Game” of 1851. It’s risky, to be used only by chess giants. But the poem by this giant of Peruvian poetry doesn’t begin as iChess.net says the King’s Gambit does (1E4). Rather, it opens in the middle of it all, in media res of the piece-flying, pawn-raging, and wild abandon. It’s a move not to begin, but to counter.

Thanks to translator Anthony Seidman and publisher Cardboard House Press, Hinostroza’s 1971 masterpiece has made its long-anticipated debut in English. Octavio Paz praised its potential to shake Latin American poetry early on, and some compare its risk-taking impact to that of fellow Peruvian César Vallejo’s iconic Trilce (1922). The collection is known for its incorporation of symbols (zodiac signs, mathematic equations, a compass), its multilingualism (English, French, Italian, and Latin, alongside the Spanish), and dense referentiality (Hamlet, the bubonic plague, the Cunningham chess defense, Archibal MacLeish, Anteaus, just in the first poem). This is certainly a difficult text to translate, and Seidman rises to the task. His version crisply shapeshifts to match the fluctuating demands and demanding fluctuations that Hinostroza places on the lyric.

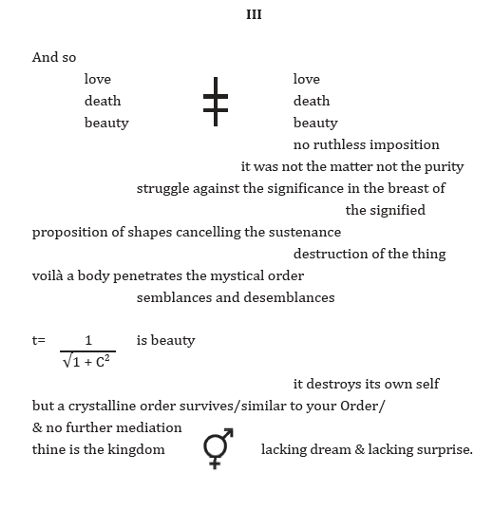

Each of the collection’s sixteen poems uniquely disorients the reader within the poetic playing field. Take, for example, this excerpt from “Hommage à Vasarely”:

Mathematical equations, ampersands, slashes, and a fusion of the male and female sex symbols serve as connective tissue that rules out any traditional reading. The content morphs from metaphysics to aesthetics, linguistics, and biblical paraphrase. Titled after the major figure of Op Art (a style of visual art that uses optical illusions), the poem quite literally pulls your eyes in different directions. There is poetic dizziness and chaos, not to mention the eye-straining task ahead: What is real? What is illusion? That nothing is exactly as it seems is one fitting description of Hinostroza and Seidman’s poetic undertaking more broadly. “And, by then, Reality was // an impetuous phantasmagoria,” we encounter just a handful of lines in.

The task of seeing differently accompanies each poem. In this regard, that Hinostroza begins by consciously situating the book on a chessboard is significant, and not only because it feels out of place. It appears in the first poem as an ominous yet theatrical arena of regulation and containment:

000000000000000000000000000000000/Act V. Curtains/

00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000The Implacable sphere

00000000000the implacable laws. 64 chess squares

00000000000and the universe curves back on itself. There is no outside, there is no

00000000000escape to another dimension where all this would be the history of

00000000000the reptile, the history of the amphibian, and prehistory itself.

The poem rejects the utopic notion of another, better-evolved world just around the corner. The implicit alternative therein is to find a means for a different maneuvering across the chessboard-turned-stage.

Indeed, rules of movement traverse the collection, creating a poetic space wherein “everything proved hazardous // and everything was lost.” Within this order, bodies are pawns: moved at whim (“& a mishmash of mirrors will launch me into the past”), captured (“your body is prey/the hunter will be the director of the CIA // and NATO”), and enclosed:

00000000000Cathars = pure

0000000000000000& the world was a prison

00000000000the solitude of the body, the powerful

000000000000000000000000000000000au bout de l’angoisse

00000000000among the need from the four sides

000000000000000000000000000000000no way for the object no way for love

00000000000& someone adopted the fetal position

000000000000000000000000000000000squatting arms crossed

00000000000hands half-closed

00000000000000000powerful veil warm placenta between him and the others

At the end of anguish, there emerges a reparative potential. Like the shelter of the placenta, this search sometimes precipitates a return to the maternal (“/anamnesis of the uterine world/ // and thus the clairvoyant // does not ossify // mediates”). In other moments, the answer is love and sex, as antidote to “the terror of being only one body,” and a state of “duality against death // mystical homecoming.” The body is space of both ruin and renewal—or, more precisely, renewal within the ruin: “his body was like the rainbow // putrefied from the violence.”

But these possibilities do not obscure the task ahead: to take up in the middle of the chessboard, after the curtains have opened, and “[repair] what happened eons ago.” A preoccupation with the past, the history of power and the power of history, courses through Hinostroza’s poetry. The choice of maternal order over paternal order offers one means to undo, while attempts to reestablish meaning and relationality point to another method: “mathematics purify // E=mc2 // cleanse a body a space;” “If life > death // death = deprivation;” “a) Opacity: // thing with shape or shapeless thing.” These counter-rules construct an alternative order within the 64 squares, opening up new movement patterns.

Within Contra Natura’s deep referentiality lies another possibility. Bodies can be pawns, but they can also be actors with interpretative power over their sources. Voices recite Shakespeare, Handel, Dryden, Marx, Dante, Whitman, Spinoza, Pound, Aristophanes, among many others. Marx’s Capital is translated through astrology, the motto of the French Revolution through uterine undulations, Shakespeare’s King Lear through Brownian motion. In “Aria Verde,” Caliban’s lines from The Tempest—“Be not afeard. The Isle is full of noises, // Sounds, and sweet airs, that give delight and hurt not”—guides the speaker to see “other forests, the prehistory of carbon and the clay // mobile beasts/the ant and the lily/ // another Law, one greener and numerous.” When fused with Hinostroza’s mercurial poetics, these reworked texts of the past demonstrate that the rules and regulations of the playing board—this great stage of power and its operations—represent the true optical illusion.

And here is where I glimpse the possibility of crystallizing a book so impossible to sum up: “anamorphosis not metamorphosis,” as written in the collection’s eponymous poem. Anamorphosis refers to a distorted projection of a recognizable image, thus requiring the viewer to change their vantage point. Metamorphosis, on the other hand, designates total transformation, by natural or supernatural means. Hinostroza’s poetry rejects utopic notions of social change, and it also rejects simply waiting for the natural to take hold of the unjust. Rather, Contra Natura renews a commitment to anamorphic seeing, to the defamiliarization of naturalized order. This is notably not a task for politicians, protesters, or guerillas, but rather one particular to the poetic avant-garde: the prism for counterseeing, countersaying, and counterbeing. In other words, it’s not about beginning totally anew, but changing one’s vantage point on the game already in progress. (OL)

Shuri Kido. Names and Rivers.

Shuri Kido. Names and Rivers.

Trans. by Tomoyuki Endo and Forrest Gander.

Copper Canyon, 2022.

128 pages. $17.00.

In the end is my beginning…

In Names and Rivers, Tomoyuki Endo and Forrest Gander dizzyingly transpose Shuri Kido’s exploration of synchronous time and realization through an array of carefully selected and presented poems. Beginning with a delightful essay on Kido’s conception of time as “an encompassing palimpsest” by Tomoyuki Endo, Names and Rivers urges the reader to detach from a linear view of time and to open their eyes to the smudged writing in the margins.

This poetry endeavors to “shuck something off”—what, exactly, it seems no one is quite sure. However, there is an undertone of disconnect between the concurrent “past” and “present.” In “Kozukata,” the water flowing from Komagatake Mountain into the Shizukuishi River is “an illusion from a hundred years before,” and the present scenery becomes hazy. The illusive figure, “You,” stands at a distance from her contemporaries, as if drawn between the overlaps of time. The poets write,

Though nothing is certain,

everything is vivid.

In times to come, this also will be an illusion a hundred years old.Or—

was an artificial past

sewn into this woven topography?

These poems are conflicted; the effort to accept the contemporaneity of the past comes up against the distance there seems to be between then and now. It uncovers the question, “If everything has happened before—is happening now—then how do we know what now is?”

The urge to define is reflected in the recurrent theme of names. The overwhelming concepts of time and impermanence are accompanied by grounding specificity; Hieronymus Bosch traipses alongside plankton and dinoflagellates as a young girl dies on Mount Kailash. In “A Tiny Little Equation,” a textbook is left shut on a desk after every human has died, clinging to its equations. If there are no people, the poets ask, who is left to recognize them?

People give things names; we distinguish one thing from everything. Without this human perception, every one thing is but a part of the whole. For us, no two things can be quite the same; the closest we allow ourselves is metaphor.

But the poetry of Names and Rivers is a rejection of metaphor, a breaking of its yoke to a “wave of sameness.” Metaphors, while proclaiming equivalency, delineate in the same breath. The “lyrical disguise” of Endo, Gander, and Kido’s poetry does not obscure their intention to present a literal reality of synchronous time, of everything as everything, of an amalgamated gray encompassing all. Names and Rivers is an intense, looming permutation of Shuri Kido’s poetry. It is a hand drawn halfway from the river as two currents crash back into one. It is a call to see everything as everything, to “take to our feet, to get going,” and to continue crossing the river. (BC)

Wang Yin. A Summer Day in the Company of Ghosts: Selected Poems.

Wang Yin. A Summer Day in the Company of Ghosts: Selected Poems.

Trans. by Andrea Lingenfelter. Foreword by Adonis.

NYRB Poets, 2022.

192 pages. $16.00.

As the first comprehensive English-language collection of Wang Yin’s poetry, A Summer Day in the Company of Ghosts teems with Wang’s reflections on life’s paradoxes and obscurity, unpredictability and repetition, and so on. Beginning with “Thing That’s Not a Thing,” the first of fourteen new poems included alongside Wang’s previous works, Andrea Lingenfelter’s translations showcase how Wang observes these many paradoxes in contentment rather than in contrast with one another, aware of “the beauty” and reflecting on having “bypassed the depressing parts”:

00000000000I’ve bypassed the depressing parts but blundered

0000000000000000nonetheless into

00000000000the beauty of frozen days

00000000000the blight of mild climes

Wang is one of the most notable post-Misty Poets, and in addition to reflecting his sentiments characteristic of this generation of modern Chinese poets, Lingenfelter’s translation of A Summer Day in the Company of Ghosts advances the transtextuality found throughout his work. From referencing Tang dynasty poet Bai Juyi’s “Flower That’s Not a Flower” in the title of “Thing That’s Not a Thing,” to his fellow post-Misty Poets in “This Is the Blackest Black” and American writers in “Talking Through the Night with Robert Bly,” Wang constantly places his poetry in conversation with classical and contemporary Chinese literature as well as the literature in translation.

Through her translation, Lingenfelter continues the constant conversation across borders and literary generations Wang embeds within his work, at times functioning as a (re)translation of the literature and film which shapes his observations on love and light amid the unpredictability of life. In “Limelight/Greylight” of the eponymous third section, Lingenfelter builds upon Wang’s use of the translated Chinese title of Charlie Chaplin’s 1952 film Limelight to embody both the multifaceted nature of Wang’s poetry as well as the central role of, in her words, “a light that contains darkness” (xvi).

This paradox of light and darkness illuminates and obscures personal and historical details across each section, with Recitation taking the most political shift in focus and House of Spirits concluding with the most romantic. Wang’s emotional emphasis on the impermanence and unpredictability of life, death, and its second chances shaped starkly by his own experiences having survived two heart attacks in the summer of 2008, with “A Drop of Rain Inside a Raindrop” containing one of his few direct references to this. Lingenfelter’s translations place us within the “drop of rain inside a raindrop” of Wang’s poetic voice, where he ruminates in each poem on the multiplicities of these emotions and enables us to feel the complexity of joy within sorrow and observe each passing moment:

00000000000An umbrella, a few stunned raindrops

00000000000striking a plastic bag of peanuts

00000000000beating like my second heart

00000000000strange sister inside my body, coming back to life00000000000This isn’t sorrow, it’s just the nighttime

00000000000flash of a horse’s mane

00000000000It’s just an untimely pause

00000000000a drop of rain inside a raindrop

(SP)

Bella Creel is teaching English in Hyogo, Japan. Against her better judgment, she is on Twitter at @isabella_creel.

Cristina Correa is the recipient of fellowships and awards from the Kenyon Review, CantoMundo, Hawthornden Literary Retreat, and Cornell University, among others. Her work has appeared in Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day, Best New Poets, Missouri Review, Obsidian: Literature & Arts in the African Diaspora, and elsewhere.

Paul Cunningham is the author of Fall Garment (Schism Press, 2022) and The House of the Tree of Sores (Schism Press, 2020). He co-manages Action Books and edits the Action Books Blog.

Olivia Lott is a scholar and translator of Latin American poetry. Her latest translation, Almost Obscene by Raúl Gómez Jattin (co-translated with Katherine M. Hedeen) is forthcoming in October 2022 from CSU Poetry Center. Her scholarly writing has appeared in or is forthcoming from the PMLA, Revista Hispánica Moderna, and Translation Studies. She holds a Ph.D. in Hispanic Studies and is Visiting Assistant Professor of Spanish at Washington and Lee University. More information: www.oliviamlott.com

Sarah Pazen is a poet, translator, and visual artist from Chicago, Illinois. She is currently the editorial assistant at the Kenyon Review and an upcoming Fulbright Fellow to South Korea. She can be found on Twitter @COPINGSKILLS.

Orchid Tierney is a poet and scholar from Aotearoa New Zealand. She is the author of a year of misreading the wildcats (The Operating System, 2019) and an assistant professor of English at Kenyon College. www.orchidtierney.com @orchidtierney