“When I tension in, it hits here”

By Victoria Guerrero Peirano

Translated by Honora Spicer and Anastatia Spicer

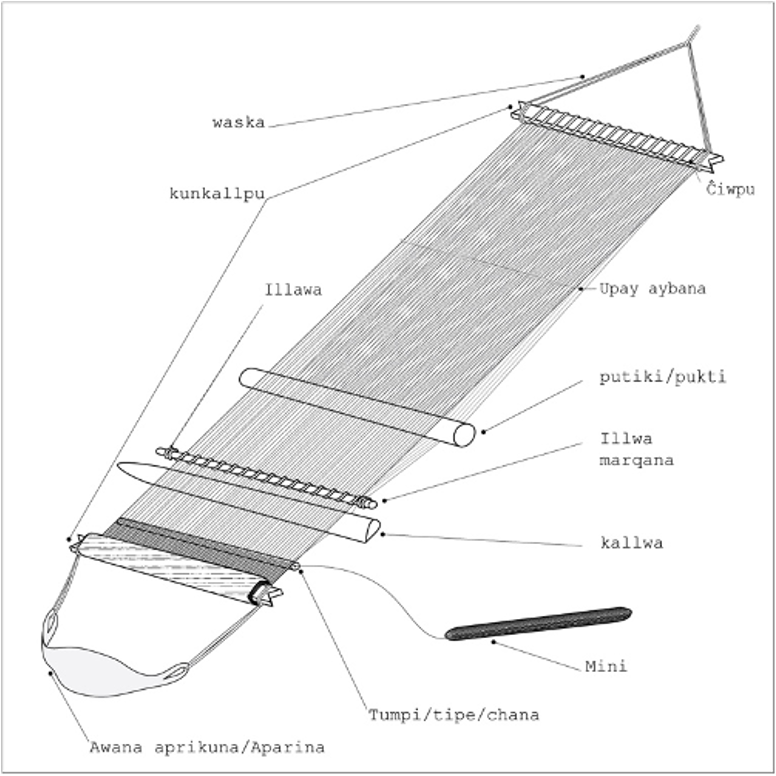

*The Kallwa or backstrap loom is associated with ancient traditions in the country and is practiced especially by women. Its use signifies the transmission of a generational knowledge and memory. It was documented by Huamán Poma de Ayala in his Nueva Corónica y Buen Gobierno (1615).

“Before the operation women wove constantly, which granted them an economic foothold and reaffirmed their local cultural identity […] For rural women living in extreme poverty, this vital rupture and ripping out signified the loss of the space of their subjectivity, given that by weaving women express their interior world along with the cosmogony of their communities. How can we measure the impact of such harm — occasioned by the indiscriminate practice of forced sterilizations?”

Alejandra Ballón, Memorias del Caso Peruano de Esterilización Forzada (2014: 42-43)

When I tension in, it hits here*

It hits here, when I tension in

Here

In the mother

Before, I’d weave

I’d weave with kallwa

Yes, with Kallwa I’ve woven

I can’t anymore

it swells

it swells

and hurts my waist

They took us tricked, see

‘it won’t take long’ and

they ligated us

Now I’m afraid

I’m afraid of weaving

I’m sick all of a sudden

And I lose it fast

When I tension in, it hits here

It hurts here

In the mother

*Text constructed from testimonies collected by A. Ballón in the Piura region from women sterilized against their will during the regime of Alberto Fujimori (1990 – 2001).

From Diary of a Proletarian Seamstress

* La Kallwa o telar de cintura está asociada a tradiciones milenarias en el país y su práctica recae, especialmente, en las mujeres. Su uso implica la transmisión de un saber y una memoria generacionales. Ha sido documentado por Huamán Poma de Ayala en su Nueva Corónica y Buen Gobierno (1615).

“Antes de la operación las mujeres tejían constantemente, lo cual les generaba una entrada económica y reafirmaba su identidad cultural local [….] Para las mujeres del campo que viven en extrema pobreza, este desgarramiento y ruptura vital significa la pérdida del espacio de su subjetividad, ya que al tejer las mujeres expresan su mundo interior así como la cosmogonía de sus comunidades. ¿Cómo podremos medir el impacto de semejante daño —ocasionado por práctica indiscriminada de las esterilizaciones forzadas?”.

Alejandra Ballón, Memorias del Caso Peruano de Esterilización Forzada (2014: 42-43)

Cuando me amarro, choca aquí*

Choca aquí, cuando me amarro

Aquí

En la madre

Antes tejía

Tejía en kallwa

Sí, en Kallwa he tejido

Ahora ya no puedo

se me hincha

se me hincha

y me duele la cintura

Nos llevaron engañando

por un ratito no más

y nos ligaron pues

Ahora me da miedo

Tejer me da miedo

De repente caigo enferma

Y me muero rápido

Cuando me amarro, choca aquí

Duele aquí

En la madre

* Texto construido en base a los testimonios recogidos por A. Ballón en la región Piura a mujeres esterilizadas contra su voluntad durante el régimen de Alberto Fujimori (1990-2001).

De Diario de una costurera proletaria

Translators’ Note

Honora Spicer and Anastatia Spicer

The text in this documentary poem derives from testimonies collected by Peruvian research-based visual artist Alejandra Ballón (http://alejandraballon.net/en/) about forced sterilizations under Alberto Fujimori (President of Peru from 1990 to 2001). We began translating Victoria Guerrero’s Diario de una costurera proletaria in 2019 through the recommendation and introduction of Peruvian poet Giancarlo Huapaya. This poem was added with the printing of the second edition by Peruvian press Máquina Purísima in Summer 2021. The publication coincided with the Peruvian presidential election cycle, in which Keiko Fujimori, daughter of Alberto Fujimori, advanced to the second round of voting, bringing the specter of the human rights abuses and corruption under Fujimorismo to the forefront of Peruvian political culture. This poem articulates a continuity with the concerns of Diary of a Proletarian Seamstress on the relationship of textile handwork traditions with nationalist politics and capitalist economics, while extending documentary poetic techniques.

Working as sister translators, we translated this poem with the same approach we used for the other poems in this collection: by each making an independent translation, then comparing our versions. We immediately noticed the stark tone: it was apparent that the poem’s speaker was articulating words in response to an absent questioner, perhaps a doctor or other authority. We wondered if the minimal quality of expression pointed to Spanish as a second, state language for the speaker, noting that the instructional diagram of the Kallwa backstrap loom which opens the poem is marked by Quechua labels. The diagram shows the Kallwa taught, as if tensioned by the presence of two absent poles: a point of attachment and the body of the weaver. This diagram oriented us to the sense that this poem was engaging with the relationship between language and object. This disembodied and decontextualized diagram also pointed to the removal of instruments of creation from bodies.

The poem is defined by words of tying: amarrar and ligar. In translating the title’s verb ‘amarrar,’ we sought a verb that pointed to the same effect as the taught Kallwa: a verb which implied a relationship between the object and the subject. ‘Tension in’ brings the sensation of the weight of the weaver’s body enabling the form of the loom, with the preposition ‘in’ affirming the binding of relationship. ‘Amarrar’ at once refers to a violence, of being tied up or tied down, of being shackled even, and this ‘tenseness’ was also necessary to extend into the verb.

The central verb of this poem is ‘ligar’ in the colloquial line that slices through the poem’s center and creates a repetition of symmetry on either side: ‘y nos ligaron pues.’ Most superficially, ‘ligar’ refers to tying tubes in forced sterilization, medically termed in English: tubal ligation. In another colloquial usage, ‘engañar’ and ‘ligar’ both refer to flirtatious, transitory romantic behavior, at once the showy lust of the state’s deceptions. Ligar referenced the tying of fibers, as well as a connotation of binding in confinement. The use of this term and the minimal but telling colloquial words that frame it convinced us that the speaker was aware of what happened to them and the severity of it and had the language to describe that. In English, ‘ligate’ shared a similar breadth of connotations, having changed little in its word structure since its Latin origins. We were especially convinced by its abstract connotations: ligation as a process of a country binding a people, and a medical process binding women both by and to the state and its language.

The penultimate stanza references the concerns of Ballón’s research: the cultural deaths occasioned by the inability of women victimized by forced sterilization to continue practicing the traditional craft of weaving by Kallwa. ‘Y me muero rápido’ stood out as a curious line implicitly referring to a ‘pérdida de conocimiento,’ a loss of both consciousness and knowledge. The speaker did not actually die, because she is present speaking as a subject. What does death in this context then mean? We considered verbs which bridged the implications of the violence of forced sterilization on individual women and their bodies, and on a cultural inheritance at large. These testimonies describe iterative deaths: of not being able to weave, of not having enough energy, of being forced differently into the market economy, of losing an inherited knowledge, and chose the colloquial phrase ‘lose it’ to encompass these overlayed effects.

This multiplicity of deaths is epitomized in the repeated line ‘En la madre.’ To be hit ‘En la madre’ is to be hit in the place that hurts the most, in the uterus, in a site of the body emblematizing motherhood, and in figurative connotations of motherland and mother tongue. We translated this line as ‘In the mother’ for the word’s significance in English, too, as an origin point of sensation and genealogy, with meanings extending towards language, belonging and sovereignty.

What are you reading right now?

We just got our copies of Victoria Guerrero Peirano’s most recent book, —La mujer—, published in August 2022 by Álbum del Universo Bakterial in Lima, Peru!

While translating this poem, we both were reading Saidiya Hartman’s Lose Your Mother, which helped us consider broad resonances of ‘mother’, as did Rosa Alcalá’s MyOTHER TONGUE (with whose mentorship we began translating Diary of a Proletarian Seamstress).

Anastatia Spicer: I am currently reading Karen Barad’s Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. I have been spending this year learning about different philosophies of the relationship between bodies and material. I have been reading through Bruno Latour’s We Have Never Been Modern, Graham Harman’s Object-Oriented Ontology and returning to Judith Butler’s conceptualization of performativity in Gender Troubles and Bodies That Matter. I am interested in bringing these ideas to archival work as a methodological approach to studying material culture. I am still in the nascent stages of this project and enjoying every moment of it!

Honora Spicer: I recently read Jose Antonio Villarán’s open pit: a story about morococha and extractivism in the américas, Teresa Cabrera Espinoza’s Las edades, JD Pluecker’s The Unsettlements: Dad, Jackie Wang’s The Sunflower Cast a Spell to Save Us from the Void, Lauren Shapiro’s Arena and everything I can find by David Buuck. I am currently working on understanding the relationship between cartography and the rise of the nation-state, and the map as a state technology of placing and managing bodies while reading Denis Wood’s Rethinking the Power of Maps.

Diary of a Proletarian Seamstress has been featured in the following locations:

Excerpts in Asymptote Journal

ALTA Conference Reading

Interview with Austyn Wohlers for Action Books featured on the Poetry Foundation blog

Academy of American Poets Poem-A-Day Feature

Temporary Archives: Poetry by Women of Latin America, ed. by Juana Adcock and Jèssica Pujol Duran, ARC Publications (2022)

Victoria Guerrero Peirano won the 2020 National Prize for Literature in Peru with the transdisciplinary essay “Y̶ ̶l̶a̶ ̶m̶u̶e̶r̶t̶e̶ ̶n̶o̶ ̶t̶e̶n̶d̶r̶á̶ ̶d̶o̶m̶i̶n̶i̶o”. In poetry, she has recently published “–La mujer–” (2022). In addition: “Diario de una costurera proletaria”, “En un mundo de abdicaciones”, “Zurita + Guerrero” and the compilation of her poetry under the title “Documentos de Barbarie (poesía 2002-2012)” which won the ProArt Prize 2015. She directs the independent publishing house Intermezzo Tropical and is a researcher in the Map of Peruvian Writers project. She holds a Ph.D. in literature and teaches at the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Anastatia Spicer is a writer and weaver. Her work engages philosophies of object network relationships by activating temporal entanglements and questioning narratives of subjecthood. She has taught weaving courses at Penland School of Craft, worked as an upholsterer’s apprentice, and currently helps operate a wool mill in Vermont. Her work has been published by The Barnard College Journal of Art Criticism, Asymptote, The Poetry Foundation, and The Academy of American Poets. In 2023 she will begin a Lois F. McNeil Fellowship for a MA in American Material Culture at the Winterthur Museum in Delaware. (anastatia.work)

Honora Spicer is a writer and experiential educator interested in place-based practices of public humanities. She has designed and led expeditionary learning programs, teaching literature, history, and Spanish language while mountain biking, mountaineering, and paddling. Her translations, poetry and essays have been published in Cardboard House Press, The Academy of American Poets, Tripwire, Jacket2, Asymptote, Latin American Literature Today, World Literature Today, The Rumpus, and elsewhere. She is based in Providence, RI and is writing a Ph.D. in the History Department at Harvard University. (honoraspicer.com)

Poesía en acción is an Action Books blog feature for Latin American and Spanish poetry in translation and the translator micro-interview series. It was created by Katherine M. Hedeen and is currently curated and edited by Olivia Lott with web editing by Paul Cunningham.