Part V

From [INCOGNITA FLORA CUSCATLANICA]

By Elena Salamanca

Translated by Ryan Greene

PART V

If we imagine the flower

is symbol

and not flower.

❁

Those flowers without being flowers which grew

even under the ash

and were described as:

[Pseudobombax ellipticum]:

“Prehistoric furry flower

that could be flower

or animal.”

[Amaranthus retroflexus]:

“Which grows on riverbanks

with a hot, furry leaf

because it’s thought it once was a flame.”

[Myrtaceae]:

“Shrub from the Southern hemisphere

before South existed.

Though it’s southern, this family who has colonized all habitats,

demonstrates that geopolitics isn’t solely a human matter.”

[Polygonum aviculare]:

“Bloodthirsty.

Known as knotgrass and birdweed.

Neither denomination is related to the other.

Semiotics doesn’t always triumph in language.”

[Lantana camara]:

“Shrub verbena.

Is born when consumed by fire

from Chalatenango to Morazán

on the sites of the scorched earth.”

[Gomphrena perennis]:

“Siempreviva.

Doesn’t need water or fertile soil to bloom.

Sometimes confused with other weeds,

no one cares how many names it has:

perennial amaranth,

Santa Lucia flower,

occucha,

white mallow, violetilla,

wild violet,

prayer flower,

dry love,

Katya Miranda,

Carla Ayala,

Jimena Ramírez Granados,

Flor García,

Simply flor.

No one cares how many names it has.”

8 thousand years ago, these plants grew in the Apaneca range.

No one knew what the plant kingdom was yet.

Nor did there exist kingdoms or injustices

and the only law was the order lava left in its wake.

❁

Centuries ago,

a poet

said:

“In my hands I hold the flower of all the ages.”

But he never held the queen protea,

which burns before it’s even born.

I walk trembling through the earth’s leaps:

I was statue, was axolotl, was woman,

I had teeth and petals,

I had sepals and ovaries.

And I waited,

for centuries,

for you to untie the blindfold from my eyes,

for you to whisper where you were

in the labyrinth of History.

You didn’t say anything.

Not even: continent.

Corn, bean, squash.

Or comet.

Nor did you say when you would return.

Meanwhile I,

surrounded by the volcanic stone,

am still searching for

the Poet’s cadaver.

[To Roque Dalton]

[In memory of my grandmother, Rosa Elena Martínez (1931-2017),

who taught me, when I was young, the fantastical names of the flowers]

❁

PARTE V

Si imaginamos la flor

es símbolo

y no es flor.

❁

Esas flores sin ser flores que crecían

aún debajo de la ceniza

y fueron descritas como:

[Pseudobombax ellipticum]:

“Flor prehistórica y peluda

que puede ser flor

o animal.”

[Amaranthus retroflexus]:

“Que crece a orilla de los ríos

de hoja peluda y caliente

porque se considera que antes fue llama.”

[Myrtaceae]:

“Arbustiva del hemisferio Sur

antes de que existiera el Sur.

A pesar de ser sureña, esta familia que ha colonizado todos los hábitats,

demuestra que la geopolítica no es solo cosa humana.”

[Polygonum aviculare]:

“Sanguinaria.

Conocida como cien nudos y lengua de pájaro.

Ninguna denominación tiene relación con la otra.

La semiótica no siempre triunfa en el lenguaje.”

[Lantana camara]:

“Cinco negritos.

Nace cuando se consume el fuego

de Chalatenango a Morazán

en los sitios donde fue la tierra arrasada.”

[Gomphrena perennis]:

“Siempreviva.

No necesita agua ni tierra fértil para florecer.

A veces confundida con otra hierba,

a nadie importa cuántos nombres tenga:

amaranto perenne,

flor de Santa Lucía,

ocucha,

malva blanca, violetilla,

violeta silvestre,

flor de la oración,

amor seco,

Katya Miranda,

Carla Ayala,

Jimena Ramírez Granados,

Flor García,

Simplemente flor.

A nadie importa cuantos nombres tenga.”

Hace 8 mil años, crecieron estas plantas en la sierra de Apaneca.

Nadie sabía aún qué era el reino vegetal.

No existían tampoco reinos ni injusticias

y el orden que dejaba a su paso la lava era la única ley.

❁

Dijo,

hace siglos,

un poeta:

“Tengo en mis manos la flor de todas las épocas”.

Pero jamás tuvo a la reina protea,

que quema desde antes de nacer.

Camino temblorosa entre los saltos de la tierra:

fui estatua, fui axolote, fui mujer,

tuve dientes y pétalos,

tuve sépalos y ovarios.

Y esperé,

por siglos,

a que desataras la venda de mis ojos,

a que susurraras dónde estabas

en el laberinto de la Historia.

No dijiste nada.

Ni siquiera: continente.

Maíz, frijol, calabaza.

O cometa.

Tampoco dijiste cuándo ibas a volver.

Mientras yo,

entre la piedra volcánica,

busco aún

el cadáver del Poeta.

[A Roque Dalton]

[En memoria de mi abuela, Rosa Elena Martínez (1931-2017),

quien me enseñó, cuando era muy pequeña, los fantásticos nombres de las flores]

❁

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This poem is dedicated to my grandmother Rosa Elena Martínez (1931-2017) and to the memory of Roque Dalton (1935-1975), murdered by his fellow members of the ERP and whose crime remains unpunished.

It was also inscribed in the memory of and thanks to Edy Albertina Montalvo (1928-2020), the first woman who dedicated herself to the study of botany in El Salvador and who founded the Herbarium of the Universidad de El Salvador and the Herbarium of the Jardín Botánico La Laguna.

This poem is based on the scientific investigations by the archaeologists Payson Sheets, Robert Dull, Paul Amaroli, Paul Daugherty; and the biologist Pablo Galán at the magazine Pankia.

The quoted phrase “Tengo en mis manos la flor de todas las épocas” is a paraphrase of a line in a poem by W.H. Auden which I read once and whose title I don’t remember.

The italicized scorched earth refers to the military operations of the Salvadoran army during the civil war (1980-1992). Under the term “scorched earth,” diverse towns, districts, and villages in El Salvador were burned, destroyed, and massacred, such as El Sumpul, in Chalatenango, and El Mozote, in Morazán. This description is a reference to the piece that I collaborated on with the photographer Fred Ramos in 2021, called “Memoria vegetal de la guerra (Vegetal memory of the war)” about the trials of El Mozote.

The names of the girls and women that appear as common names of the [Gomphrena perennis] or siempreviva are of femicide victims in El Salvador, the first occurring in 1999 and the rest between 2017 and 2021.

The rest of the vegetal knowledge comes from my grandmother, Rosa Elena Martínez, who taught me, when I was very young, the names of the flowers, and who also taught me to keep flowers pressed in books. All of our life together we gathered flowers and leaves from the gardens of all of our houses: the one during the war, the one after the war, and the final one, where she died on November 20, 2017.

To love is to plant a garden.

❁

NOTA DE AUTORA

Este poema está dedicado a mi abuela Rosa Elena Martínez (1931-2017) y a la memoria de Roque Dalton (1935-1975), asesinado por sus propios compañeros del ERP y cuyo crimen sigue impune.

También se inscribe en la memoria y el agradecimiento a Edy Albertina Montalvo (1928-2020), la primera mujer que se dedicó a estudiar la botánica en El Salvaodr y fundó el Herbario de la Universidad de El Salvador y el Herbario del Jardín Botánico La Laguna.

Este poema está basado en las investigaciones científicas de los arqueólogos Payson Sheets, Robert Dull, Paul Amaroli, Paul Daugherty; y el biólogo Pablo Galán en la revista Pankia.

El frase comillada “Tengo en mis manos la flor de todas las épocas” es una paráfrasis que proviene de un poema de W.H. Auden que leí una vez y ya no recuerdo el título.

La cursiva de tierra arrasada hace referencia a las operaciones del ejército salvadoreño durante la guerra civil (1980-1992). Bajo el apelativo de “tierra arrasada” fueron incendiados, destruidos y masacrados diversos pueblos, cantones y caseríos de El Salvador, como El Sumpul, en Chalatenango, y El Mozote, en Morazán. Esta descripción es una referencia de la obra que realicé junto al fotógrafo Fred Ramos en 2021, titulada “Memoria vegetal de la guerra”, sobre los juicios de El Mozote.

Los nombres las niñas y mujeres que aparecen como nombres comunes de la [Gomphrena perennis] o siempreviva son los de víctimas de feminicidio en El Salvador, ocurridos, el primero en 1999 y el resto entre 2017 y 2021.

El resto del conocimiento vegetal viene de mi abuelita, Rosa Elena Martínez, quien me enseñó, muy niña, los nombres de las flores, y quien también me enseñó a guardar flores prensadas en libros. Toda nuestra vida juntas recolectamos flores y hojas de los jardines de todas nuestras casas: la de la guerra, la de después de la guerra, y la definitiva, donde ella murió el 30 de noviembre de 2017.

Amar es hacer jardín.

❁

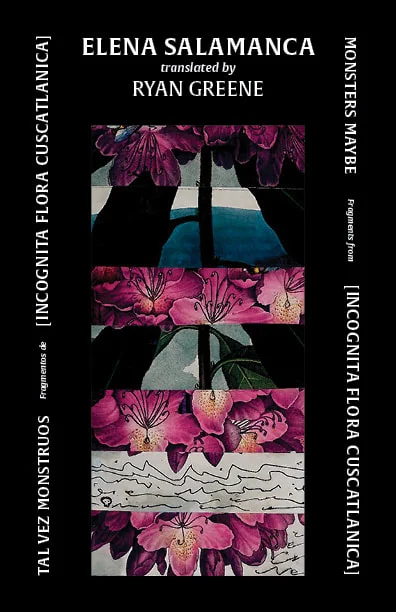

Monsters Maybe, fragments from [INCOGNITA FLORA CUSCATLANICA] is available from Mouthfeel Press.

Elena Salamanca is a writer and historian from El Salvador currently living in Mexico. She has published Tal vez monstruos // Monsters Maybe (2022), La familia o el olvido (2017 and 2018), Peces en la boca (2013 and 2011), Landsmoder (2012 and 2022), and Último viernes (2008). Her most recent books, Claudia Lars: La niña que vio una salamandra (2020) and Prudencia Ayala: La niña con pájaros en la cabeza (2021) are the first two volumes of her “Colección Siemprevivas” series dedicated to the stories of more than 40 women who were born or lived in El Salvador between the 18th and 20th centuries. Her work has been translated into English, French, German, and Swedish. Since 2009, she has combined literature, performance, memory, and politics in public space. She is a doctorate candidate in History from the Colegio de México, and her thesis investigates the relationships between Central American unity, citizenship, and exile. She earned her master’s in History from El Colegio de México (2016) and the Universidad de Huelva, Spain (2013).

Ryan Greene is a translator, book farmer, and poet from Phoenix, Arizona. He’s a co-conspirator at F*%K IF I KNOW//BOOKS and a housemate at no.good.home. His translations include work by Elena Salamanca, Claudina Domingo, Ana Belén López, Giancarlo Huapaya, and Yaxkin Melchy, among others. His recent bilingual collections with Elena Salamanca include Landsmoder, which won the 2020 Stories Award for Poetry put on by Not a Cult, and Tal vez monstruos // Monsters Maybe, which was the inaugural title in the CLASH! chapbook series published by Mouthfeel Press. Since 2018, he has co-facilitated the Cardboard House Press Cartonera Collective bookmaking workshops at Palabras Bilingual Bookstore. Like Collier, the ground he stands on is not his ground.

Poesía en acción is an Action Books blog feature for Latin American and Spanish poetry in translation and the translator micro-interview series. It was created by Katherine M. Hedeen and is currently curated and edited by Olivia Lott with web editing by Paul Cunningham.