Johannes Göransson: Maybe we can start biographically. Where were you born? How long have you lived in Sweden? What brought you there?

Maria Hardin: I was born in Florida. I’ve been living in Sweden since 2011. My mother moved from Sweden to America after high school and I grew up thinking that one day I would do the same but in reverse. I moved as soon as I could.

JG: How do you think living in another country has affected your writing?

MH: Poetry has something to do with the way language feels in my mouth. I can almost taste it. I suspect that comes from growing up bilingual. The sensation intensified when I moved to Sweden and started living in a language other than English.

I am flooded with such a strong sense of kinship when I read other bilingual and multilingual poets. It wasn’t until the writing workshop Hekseskolen, led by Olga Ravn and Johanne Lykke Holm, that I encountered poetry that played with multiple languages in one piece. The way poets like Cia Rinne and Mette Moestrup blend languages in their writing felt like coming home. As the child of an immigrant, English and Swedish have always been intertwined—sometimes in the same sentence. This experience isn’t really reflected in my book but it is something I have been thinking a lot about now that my mother is gone.

JG: Do you feel at all part of the Swedish or Scandinavian literary scenes?

MH: I love Danish poetry from afar. The Danes are so good at striking a balance of taking the craft of writing very seriously while still being playful and cool. I tend to only go to readings in Stockholm if there are visiting writers because I am allergic to Swedish poet voice. There are plenty of poets that don’t do it, but I just get so riled up whenever I hear it that it kind of ruins the whole event for me, so I’d rather just avoid it all together.

That being said, my writing is definitely in conversation with writing that is happening here. I think that is pretty impossible to avoid. If anyone reading this wants to check out contemporary Swedish poetry, I’d recommend putting https://pralin.xyz in google translate. Is that sacrilege to advise?

JG: Do you feel, like Gertrude Stein, that living somewhere else has allowed you to be “alone” with the English language?

MH: Unfortunately, English permeates everything here. I am obsessed with all of the ad campaigns written in English for no discernible reason. The subway is currently plastered in huge posters that say “There’s a new vagina in town. You can cunt on us!” Living here has definitely heightened the absurdity of English.

JG: Yes, it’s hard for me to imagine being alone with any language at all. You write: “the rose is a rat the rat is a rose.” Maybe this is the opposite of Stein’s “a rose is a rose is a rose” — i.e. the language becomes corrupted by sound — “the feeling in the mouth” – and the rose becomes a rat. The bodily as the site of corruption.

MH: I have thought of that line as a kind of continuation. I corrupt Stein’s soft S into a hard T and in the moment of transmutation uncover something. The rose has always been a rat. Girlhood is being a rat and a rose at the same time. It’s having a 10-step Korean skincare routine but forgetting to change your underwear for three days. I adore the decay that exists just below the surface of a girly facade. Sick girls are intensely aware of this dichotomy. No one wants to help a rat, so in order to receive proper care we have to perform bloom even as we are oozing with necrotizing sores.

JG: I am reminded of your invocation of Blake’s “sick rose” in your “sick sonnets,” sonnets which you told Paul Cunningham in an earlier interview are “ infected, inflamed, gorging on language, high on codeine, and totally bored. ”I also think about this interview with Kim Hyesoon, where she tells Ruth Stone that the source of her poetry is a childhood illness, when “something like poems were filling up my body.” Personally I always think back on being 10 or 11, and having to spend the summer in the hospital for extreme sinus infection (my face swelled up like a balloon), as the source of my own poetry (I had been at a play about the Paris Commune right before the sickness, and kept having these weird hallucinations about revolution as I was stuck in the hospital unable to eat the hospital food).

MH: Poems filling up my body is how I experience poetry as well and why it feels so different from other types of writing. I think my job as a poet might just be to empty myself—to become a vessel—and then spill, or barf, onto the page when I can’t contain the words any longer. I am reminded of a quote by the artist Jesse Darling that I often return to, “as a failing body I joined the collective failure of all bodies, and from this position full of holes I stream out towards the holes in others and in this way, we might breathe one another, feed one another, flow through one another and sometimes fill up.”

JG: What gives sickness such a strong connection to poetry? Is poetry necessarily on the side of sickness in our health-obsessed culture?

MH: When I am in a flare, I crave sick writers. I don’t mean that I want to read about sickness. It’s that I have a deep need to connect with other people who have communed with the void.

Sickness is psychedelic. It is a falling out of time. Multiple people have thought that I was talking about crypt time when I’ve said something about crip time. In a way, it is a crypt time. Sickness is a re-orientation to ephemerality and death. All that matters is that one day we will all die but most people are too scared to even think about it. Poetry lets us get close.

JG: What’s the relationship between feeling the language in one’s mouth and sickness? Can sound — or rather sonic transformation, noise, slipperiness, punnery — be a sickness?

MH: For me, it has been connected to the myriad of medications and treatments that I have experienced and all the ways they have affected my perception. There’s the expected mentally influencing meds like codeine, Xanax and Ambien but something I’ve never read about is how a 6 hour IVIG infusion can induce a trance-like mental state. I try to write from, or through, all my treatments to see what happens to my relationship with language under their influence.

When it comes to sound, I have misophonia. Some sounds make my skin feel like it is being peeled off with a cheese grater or like my brain is glitching. The flip side of this hypersensitivity is that nice sounds can feel like waves of calm pulsing through my veins. I suppose sound can be a sickness but I am more interested in its healing potential.

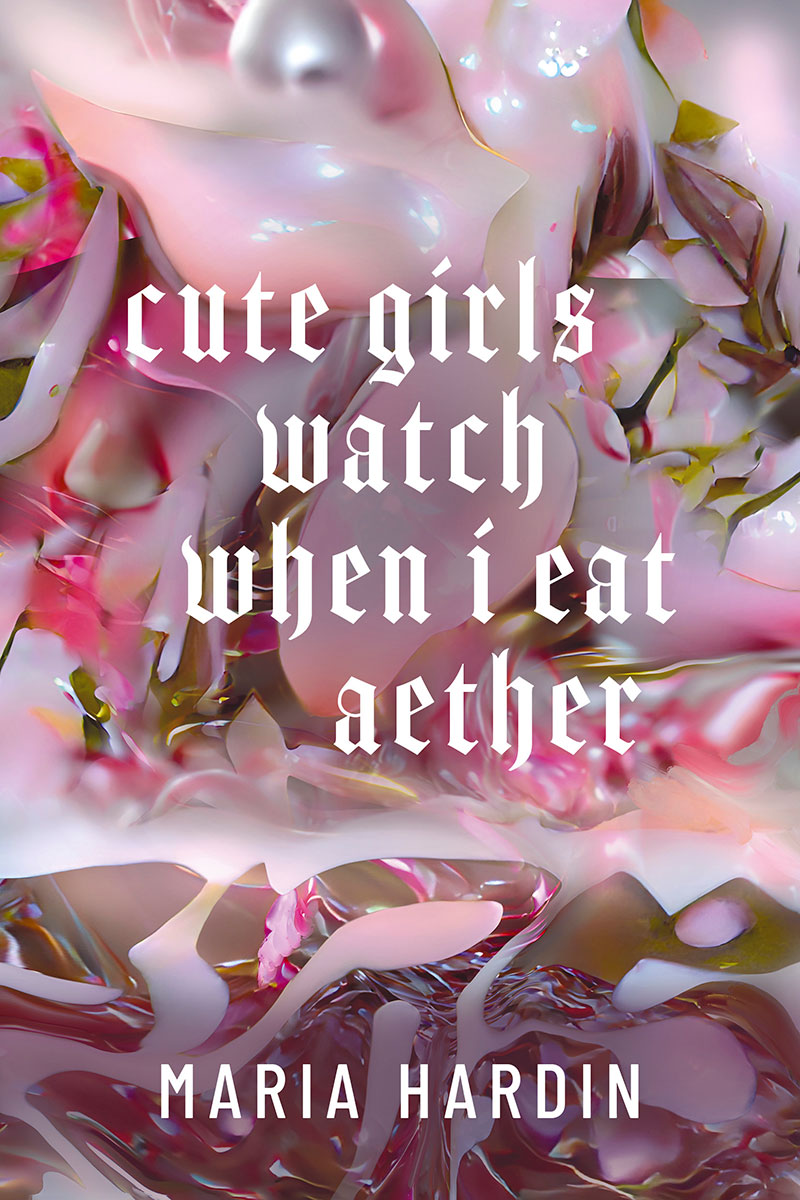

JG: The title of the book references Hole’s “Miss World” (which I also pay homage to in my book Entrance to a colonial pageant in which we all begin to intricate) – it also rhymes for me with the title of Ravn’s first book (I Eat Myself as Heather – Girl Mind). I think of the idea that art is connected somehow to aether, reaching out to the aether, in order to find “the news that stays news.” Eating aether is quite different! I think of that other great Hole song: “I want to be the girl with the most cake.” Perhaps the cake – like the sickness – comes from eating. What associations do you have with the Hole quote? What made you use it (in a corrupt form) for the title of your book?

MH: Encountering the title of Ravn’s book felt like a prophecy. I saw it right before learning that my immune system was “eating” my muscles. The Swedish translation of the title “Jag äter mig själv som ljung” played in my mind on loop for months. To be honest, I’ve never even read the book. The title was what I needed at the time. It was a way for me to think about disease outside of the vocabularies of war that are often associated with illness. It made me realize how much I needed to find my own vocabulary for what was happening to me.

Every Sunday, for years, I injected myself with a low dose chemo medication that I started thinking of as aether. It felt like a process of becoming aether. “Miss World” isn’t about chronic sickness but it could be. It became a kind of anthem. Referencing and corrupting the song was a way of winking at riot grrrl and gurlesque. Without those movements my writing wouldn’t exist, but I write for girls who doubt that they are real. (I think girl is a genderless concept.) I barely realized I had a body until I started experiencing so much pain that I couldn’t dress myself.

JG: I just read on Twitter, David Leftwhich wrote: “I just finished Some Girls Walk Into The Country They are From” by Sawako Nakayasu & started Cute Girls Watch When I Eat Aether (which is great so far) while watching Scavengers Reign and they all seem connected (beyond mental proximity) in creating a dark aesthetic for our time.” What might this figure of the “girl” give to poetry or art in general in trying to metabolize “our time”?

MH: My first love is sci-fi. That tweet makes me so happy.

In December, long after the manuscript was finished and accepted for publication, Dazed, The Cut, and NPR were all writing about how 2023 was the year of the girl: girl math, girl dinner, hot girl summer, rat girl summer, girl, girl, girl. I was a little nervous that by the time my book came out everyone would be sick of all this girl talk but it doesn’t seem to be slowing down. TikTok’s algorithm has enabled all the contradictions of girlhood to be witnessed in a very public way. We are learning that all of these private little things that we’ve done but never really spoken about because we thought that it was weird or shameful are turning out to be so commonplace. It’s bringing girls together and horrifying non-girls. I don’t dare speak for art in general but it makes me hopeful and curious whenever perspectives that have been dismissed are voiced.

JG: Can you talk about your visual artwork? To what extent does it intersect with your poems?

MH: At the moment, I am collecting water samples from miraculous medieval lagoons and magic viking springs that heal diseases and turn you into a virgin.

There is a great essay by Kathrin Busch called “Phantasmagorical Research: How Theory Becomes Art in the Work of Roland Barthes.” She writes about how Barthes thinks that a hypersensitive consciousness devoted to aesthetic thought is a drug. For me this drug is a medication. I don’t think that art can heal me, or that art is therapy, or anything gross like that, but devotion to aesthetic thought is what keeps me here.

Raw Meadow Eternity with Sam Druant

When I am in an intense flare, I can spend days hyper fixated on a single phrase. “Honeysuckle abandonment” the only thought in my brain. Despite what might be happening to my body, it is pure bliss. I love being haunted by an idea.

My poetic practice often leaks into my artistic practice. For instance, I was curious about how the psychological experience of reading changes depending on the context. So, a poem from my book was recently shown as “poetry plastique” at Gothenburg’s Konsthall.

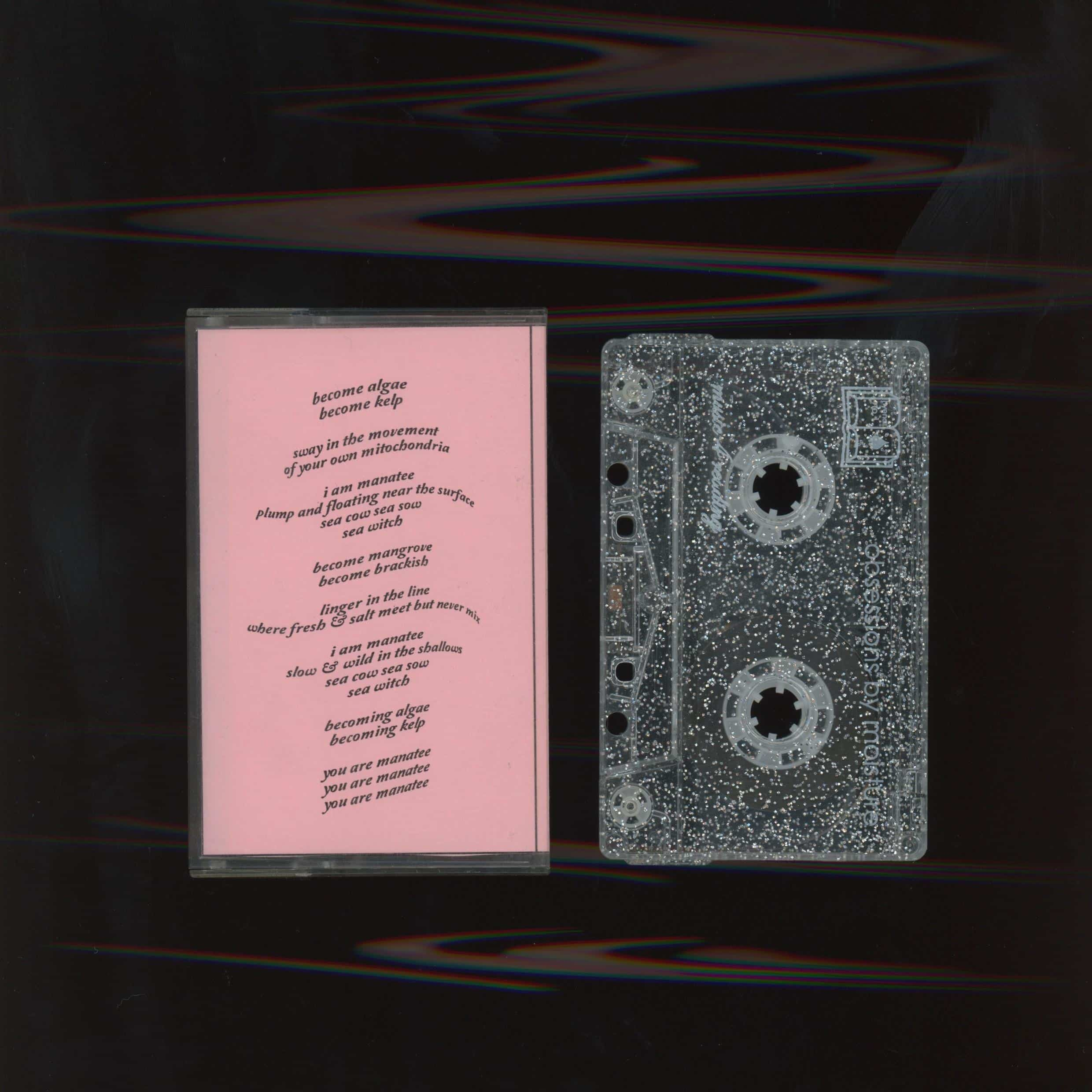

I tend to mostly work with installation, artist books, video, and site specific sculptures. The medium usually emerges from the conceptual idea. I have used AI to create a perfume that smells like eternity and led radio seances for automatic writing. I’ve also collaborated with musicians to create different sound sculptures.

Maria Hardin is a Swedish-American artist and bilingual poet based in Stockholm. She holds an MFA in Fine Arts from HDK-Valand (2023). From 2016-2022 Maria published under the pen name Mai Ivfjäll. Maria is the author of the chapbooks Into Longing Vast Rose (If a Leaf Falls Press, UK), Andakt (AFV Press, NO), Weep Hole (Sad Press, UK), and Sick Sonnets (Radioactive Cloud, USA). Her writing has appeared in American Chordata, Burning House Press Online, Denver Quarterly, Fanzine, Gutter, Ligeia, Odiseo Magazine, Ordkonst, Populär Poesi, SLFFCK, Spam Zine, Spectra Poetry, Tidskriften Provins, Wigleaf, Vakxikon’s Greek Anthology of Young Swedish Writers, and elsewhere. Her debut poetry collection, Cute Girls Watch When I Eat Aether, was published by Action Books (2024). Maria is interested in the potential of language to alter consciousness. Moving across mediums, she brings language from the page, and screen, into the physical world by creating installations, sound sculptures, and site specific works where audiences can encounter sick time, feminine wounding, and mystical suspensions of coexistence. Her work has been exhibited across Scandinavia, and her writing has been published in Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, England, Greece, Norway, Scotland, Sweden, and the United States of America