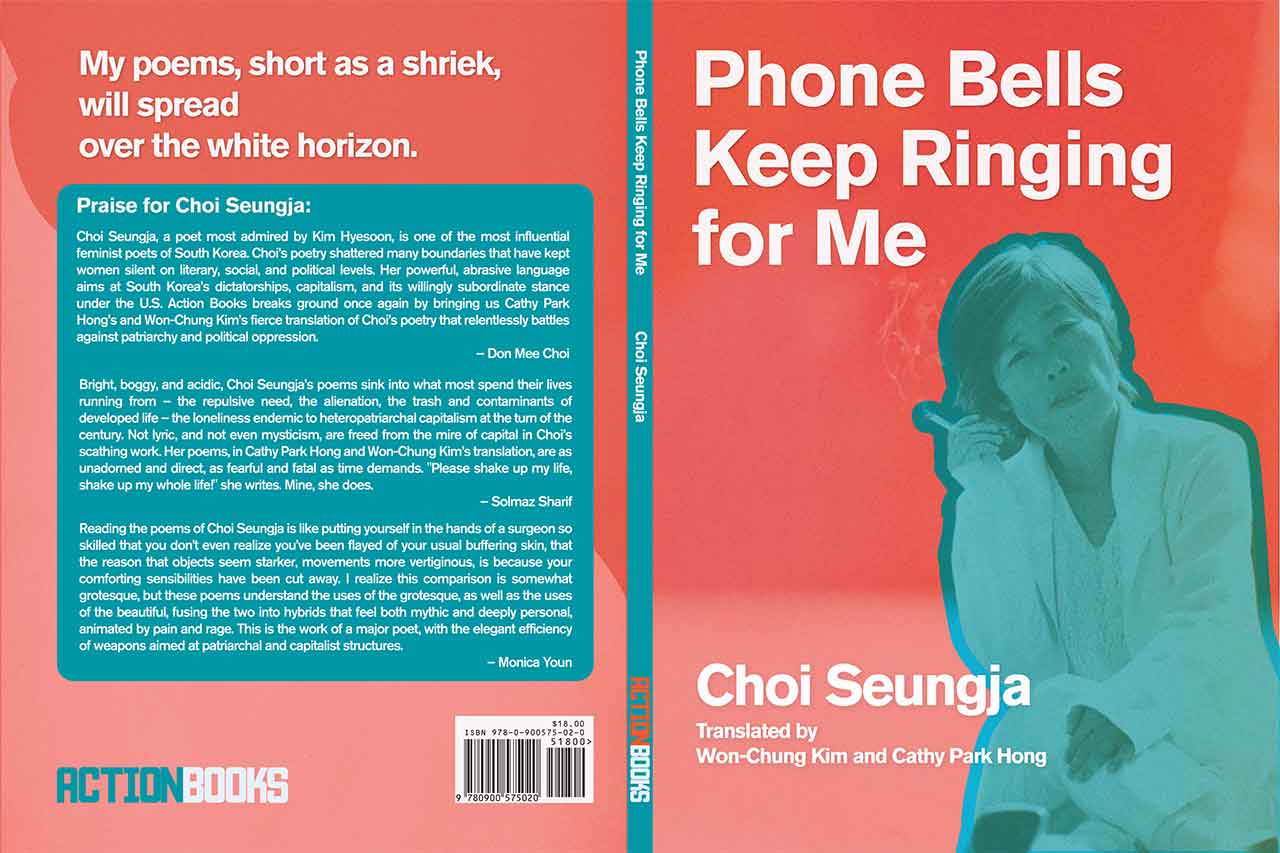

Phone Bells Keep Ringing for Me

Choi Seungja

Translated by Won-Chung Kim and Cathy Park Hong

ISBN 978-0-900575-02-0 | $18 | 102 pages | October 1, 2020

My poems, short as a shriek,

will spread

over the white horizon.

This volume selects poems of many decades by one of the most startling, distinctive, and influential feminist voices in contemporary Korean poetry. Against the limits society would erect around her, Choi Seungja’s poetry trains a keen attention on everyday objects and situations until loneliness, time, emptiness, love, death and even brief-lived delight glow with uncanny luster. Won-Chung Kim and Cathy Park Hong’s translations accentuate the simplicity and boldness of Choi’s vision, her perfect aim.

REVIEWS OF PHONE BELLS KEEP RINGING FOR ME

Many of Choi’s poems are lonely, the loneliness that comes with living, sure, but also the loneliness of waking each morning to be yoked by capitalism and knowledge of inevitable death. See: “Lonely Women.” This is not to say that these poems are without tenderness or joy. Only that life sucks (mostly) and then you die, the in-between punctuated by rain and love and endless dualities. In “Toward You,” Choi writes of death as “gripping life.” I’d argue that death is gripping each of these poems as well, just as it holds each of us by the scruffs of our necks.

The poems in Phone Bells Keep Ringing for Me span decades. They are intimate, brutal, courageous, sometimes grotesque, sometimes hilarious or kind, always ambivalent and deeply engaged with, as Choi says, “charting a way.” Great sorrow and tragedy suffuse these poems, but they keep the shadow space alive, habitable. Despite everything arrayed against Choi—her society’s “ideology of happiness”—she not only builds a den in the weeds, an island in a spreading sea, but charts a course for others to follow. There is, in Choi’s poems, the origins of a community-to-come, the one for which Choi has sorrowed and longed all her life.

Phone Bells Keep Ringing for Me (translated by Won-Chung Kim and Cathy Park Hong), declares poems “short as a shriek,” both witness and battle cry that reminds us that canons full of male authors gloss over societal structures that have kept women largely silent in literature as well as politics and culture via a strict and narrow set of rules of what is “acceptable” behavior–and art–by women. Korean poetry is often marked by the pastoral, and poetry by women comes with expectations to be lyrical and decorous in subject. Choi, then explodes that idea.

Seungja sensitively captures fragile, yet sometimes violent moments. Her genius is in articulating these moments, excising parts of her spirit to share with the rest of us.

Choi’s chthonic poetics imagines the self as something shared between the planet, the body, and the aether. Shifting between states of dramatic physicality and complete abstraction. The phone is real and in front of us, but the voice inside is immeasurable.

PRAISE FOR CHOI SEUNGJA

Choi Seungja, a poet most admired by Kim Hyesoon, is one of the most influential feminist poets of South Korea. Choi’s poetry shattered many boundaries that have kept women silent on literary, social, and political levels. Her powerful, abrasive language aims at South Korea’s dictatorships, capitalism, and its willingly subordinate stance under the U.S. Action Books breaks ground once again by bringing us Cathy Park Hong’s and Won-Chung Kim’s fierce translation of Choi’s poetry that relentlessly battles against patriarchy and political oppression.

—Don Mee Choi, author of DMZ Colony

Bright, boggy, and acidic, Choi Seungja’s poems sink into what most spend their lives running from – the repulsive need, the alienation, the trash and contaminants of developed life – the loneliness endemic to heteropatriarchal capitalism at the turn of the century. Not lyric, and not even mysticism, are freed from the mire of capital in Choi’s scathing work. Her poems, in Cathy Park Hong and Won-Chung Kim’s translation, are as unadorned and direct, as fearful and fatal as time demands. “Shake up my life, shake up my whole life!” she writes. Mine, she does.

—Solmaz Sharif, author of Look

Reading the poems of Choi Seungja is like putting yourself in the hands of a surgeon so skilled that you don’t even realize you’ve been flayed of your usual buffering skin, that the reason that objects seem starker, movements more vertiginous, is because your comforting sensibilities have been cut away. I realize this comparison is somewhat grotesque, but these poems understand the uses of the grotesque, as well as the uses of the beautiful, fusing the two into hybrids that feel both mythic and deeply personal, animated by pain and rage. This is the work of a major poet, with the elegant efficiency of weapons aimed at patriarchal and capitalist structures.

—Monica Youn, author of Blackacre

ABOUT CHOI SEUNGJA

Choi Seungja is one of the most influential feminist writers in South Korea. Born in 1952, Choi emerged as a poet during the 80’s, a turbulent and violent decade which saw nationwide democracy movements against the authoritarian government. She made her literary debut in 1979 and shortly after became an icon of youth and freedom in Korean literature, being dubbed “the common pronoun of the 80s’ poets.” She published Love in This Age (1981), A Happy Diary (1984), The House of Memory (1989), My Grave Is Green (1993), and Lovers (1999). 2001 saw the inception of a mental illness that has kept her in and out of hospitals ever since. A community of poets and presses, led by the renown poet Kim Hyesoon, came to Choi’s aid to help lift her out of poverty and enable her to continue to write. Choi returned to publishing with the volumes Alone and Away (2010), for which she received the Daesan Literary Award (2010) and Jirisan Literary Award (2010). Her subsequent publications include Written on the Water (2011) and Empty Like an Empty Boat (2016).

ABOUT THE TRANSLATORS

Won-Chung Kim is a professor of English Literature at Sungkyunkwan University in Seoul, South Korea. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Iowa, and has published articles on American ecopoets including Gary Snyder, Wendell Berry, Robinson Jeffers, A.R. Ammons, and W.S. Merwin, in journals such as ISLE (Interdiscilinary Studies of Literature and Environment), CLCWeb, and Comparative American Studies. Kim has also translated twelve books of Korean poetry into English, including Cracking the Shell: Three Korean Ecopoets and Heart’s Agony: Selected Poems of Chiha Kim. Kim has co-edited with Simon Estok East Asian Ecocriticisms: A Critical Reader (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). He has also translated John Muir’s My First Summer in the Sierra and Thoreau’s Natural History Essays into Korean. His first book of poetry, I Thought It Was a Door, was published in 2014.

Cathy Park Hong‘s latest poetry collection, Engine Empire, was published in 2012 by W.W. Norton. Her other collections include Dance Dance Revolution, chosen by Adrienne Rich for the Barnard Women Poets Prize, and Translating Mo’um. Hong is the recipient of the Windham-Campbell Prize, the Guggenheim Fellowship, and a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship. Her poems have been published in Poetry, A Public Space, Paris Review, McSweeney’s, Baffler, Boston Review, The Nation, and other journals. She is the poetry editor of the New Republic and is a professor at Rutgers-Newark University. Her book of creative nonfiction, Minor Feelings, was published by One World/Random House in Spring 2020.