1.

The Voice that Is Great Within Us: For a long time this anthology by Hayden Carruth was the dominant textbook of Creative Writing programs, a text taught over and over again (maybe still is?). The very title tells you a lot about the dominant aesthetics of the program era: the belief that poetry is a voice that comes from “within.” As I pointed out in Transgressive Circulation: Essays on Translation, this model of poetry is based on what John Durham Peters identifies as the ideal of “communication”: the self is stable, communicating is about transmitting that selfhood as directly as possible. interiority.

2.

In other words, the aesthetics of the anthology is based on what I call the “gold standard” of selfhood. Another gold standard the book upholds is US hegemonic thinking: it includes not foreign poets. The voice that is great within us speaks in English.

3.

I don’t use “gold standard” casually. There is an economic basis in this kind of thinking. The same urge that drives rightwingers to call for a return to the gold standard drives their anxiety about immigrants (and really the rest of the world), about a too-much-ness (or inflation, proliferation, excess), about imitation. And the same urge can be found in the rhetoric of the voice that is great within you, the always-in-English voice, the singular voice.

4.

A key component of a lot of translingual writing and translations is to think in counterfeits. Think against gold. Think in versions. Introduces volatility, permutations, proliferations into the communication paradigm.

5.

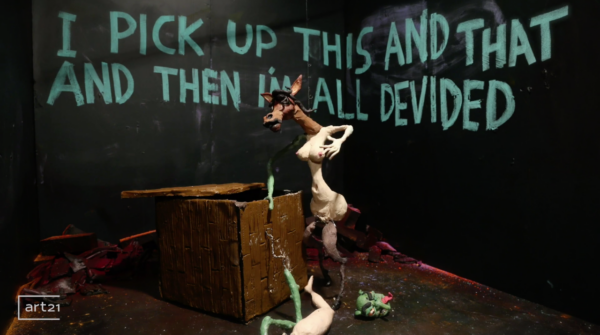

An interesting alternative to this voice of interiority can be found in those new Nathalie Djurberg/Hans Berg pieces that Madison, Jayme and Paul discussed last week on this blog. Something so striking about this new work is the use of language. It’s unclear “where” the language happens in these films: Are they coming from “within” or from the outside?

The large lettering suggests a public-ness, a loudness – maybe even a scream – but the fact that they are text in a visual piece suggests they are from within. The weird, mesmerizing music – and the fact that Berg gets credited as a co-creator – adds another layer of volatility: does the music supplement the images or are the images illustrations of the music? In other words: there are many great voices and they are coming at you from a volatile ambience, from all direction. The foreground might be background, inside might be outside.

6.

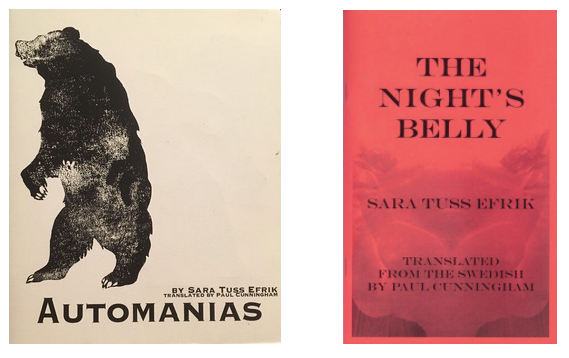

Swedish novelist/poet/performer/artist Sara Tuss Efrik works in “automanias” – she writes through other texts (or movies, music, other media). She “translates” the text but instead of looking for a spirit or essence of the text and treating the language as a reflection of this essence, she gets lost in the text, in art’s matter and other lives – sometimes her own, sometimes someone else – enter into the text in an occult manner. It’s an occult contagion.

7.

You can find a lot of her written automanias (translated by Paul Cunningham) in two chapbooks: Automanias (Goodmorning Menagerie, 2016) and The Night’s Belly (Toad Press, 2016).

8.

One day I got an email from Sara saying she had “translated” my first book, A New Quarantine Will Take My Place into Swedish. I read her translation and loved it, but – like all her automanias – it was not a conventional translation; it was also a grappling with and channeling of the text. What was “original” and version, her and me were dislocated in a powerful way. The framework was that of a horror movie: Sara Tuss Efrik standing outside Johannes Göransson’s mysterious quarantine, trying to find a way in, and then, when she gets in, encountering all kinds of horrors, including the stuff of the poem but also things from her own life (such as the overdose of a boyfriend). The language itself becomes wounded, vibrating with puns and resonances, hauntings. For example, the poem called “A Shotgun Wedding in the Ribcage of the Bourgeoisie” in the “original” book gives rise to the ghost of “Louise Bourgeois,” who becomes one of the leading characters in the new version, struggling with a sister-like Shirley Temple, who is sometimes played by Johannes Göransson.

9.

I decided I had to translate Efrik’s translation “back” into English, but in so doing I was sucked into the volatile dynamics of the automania: I began to find new directions for the text, new voices entered. We started to write back and forth, using different means and mediums. The “original” was no longer my book but that occult space where we wrote, channeled and erased voices.

(For some excerpts from this book, go to Seedings: https://durationpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/seedings-5_efrik-goransson.pdf)

10.

Last week I wrote about Agustin Guambo’s Andean Nuclear Spring (translated by Carlos Moreno, UDP). In the afterwords to that chapbook, Moreno writes: “The work of translation will always entail and generate spaces of fragility.” He argues that this fragility comes from the possibilities of different word choices. The singular, in other words, is lost, opening the text up to potentialities. Sara had made my Quarantine – that icon of hardness and isolation – into a “fragile” space, where the dead could speak to and through us. We had made the English language weak, we had opened up “the original” to a proliferation of voices – voices that may becoming from within or without. We had made the self “fragile.” We had opened up the communication channel to the noise of media. We had become mediums.

11.

In Syncope, Catherine Clement writes (trans. Mahoney and Driscoll) that syncope means the loss of self, even for a moment. It means “choosing night, a happy confusion of genres.” And later that what characterizes this night is “chaotic and unfinished.” I think of Bakhtin’s important work on monoglossia and heteroglossia – and his insight that the monoglossic work tends to promote the idea of the finished, complete work. Syncope is a loss of the self but it’s also the loss of the monoglossic illusion of language. Both gold standards are lost: poems (and poems in translation especially) can create a fragile space where the gold standard of selfhood and communication are havocked.

12.

Poetry is not communication, poetry is the art of the wound.

Johannes Göransson is the author of four books with Tarpaulin Sky Press — Entrance to a colonial pageant in which we all begin to intricate (2011), Haute Surveillance (2013), The Sugar Book (2015), and Poetry Against All (2020) — in addition to three previous collections of poems: A New Quarantine Will Take My Place, Dear Ra, Pilot (“Johann the Carousel Horse”) He has also translated several books, including Aase Berg’s Hackers, Dark Matter, Transfer Fat, and With Deer as well as Ideals Clearance by Henry Parland and Collobert Orbital by Johan Jönson. @JohannesGoranss