Nick Cave’s Soundsuits

1.

One object waits for the other to form a mouth: it sees pink lips shape to blow waste. A black object, realizing it is being watched, would normally hold a lug in, until the corner.

In fact, it knows, one should spit as little as possible, leastwise upon a floor, but here on a street, approaching a corner, in an instance where one has an audience, the black object lets go.

-from Ronaldo Wilson’s “The Black Object’s Deportment“

2.

“The aesthetic’s return is never pretty,” says Lee Edelman. The aesthetic’s return might not necessarily be beautiful. Does that mean it might be grotesque or grotesquely beautiful? Monstrous? Obscene? Queer?

Edelman seems to want to turn aesthetic against itself.

3.

In his recent talk at Emory (“Queerness, Afro-pessimism, and the Return of the Aesthetic”) Edelman spoke of the “myriad name of the void that disturbs ethics,” naming ethics an “aesthetics.” Edelman believes the aesthetic is always profoundly political:

The valuation of the aesthetic for its independence from the world of “unchallengeable fact” turns out to have been the projection of a political vision all along—a vision wholly determined by the “facticity” it claims to escape. As if speaking directly to Castiglia, for whom the return of the aesthetic explicitly hinges on the imaginative “suspension of reality”—that is, on the suspension of the political, social, and cultural reality of the world as given—Rancière writes: “aesthetic metapolitics cannot fulfill the promise of living truth that it finds in aesthetic suspension except at the price of revoking this suspension, that is of transforming the form into a form of life” (Castiglia 402; Rancière 39).

Edelman also claims that the aesthetic is not the other of politics. Thus, Art—Poetry—is always political. This is why I believe that poets who consciously claim their poetry is not political—artists who go out of their way to describe their art as apolitical—are some of the most intensely political artists of all.

Edelman explains that the “void” (as mentioned above) can be interpreted as the non-normative. “The Queer, the Black, the Woman, the Trans person.” The void is what disturbs social norms. Poetry that inhabits the void (or vice versa). Noise that pollutes.

Art—a spectacular and dissentous masque!

He also uses the Lacanian “thing,” the beyond of the signified, to approach the plus sign that appears in LGBTQ initialism. The ab-sens from collectivity (and resulting jouissance):

Think of it as the plus sign that marks the impossible closure of the sequence that begins with LGBTQQIP2SAA+

What does its name leave out? The plus sign aspires to terminate absence.

Edelman goes on listing tenants to the void or ab-sens. (“The Queer, the Black, the Woman, the Trans person, the Muslim, the Jew…”). He says “desire always assumes there’s an object that can satisfy it.” No doubt, inclusivity is a necessary goal. I feel I should be writing toward that plus sign, but I do so remaining skeptical of the normative. Depending on the person, visibility can be a dangerous thing. As a poet, I am content with inhabiting the between of visibility and invisibility.

4.

As a queer artist, closure does often feel like an impossibility. “Faggot.” The word always pulls me from the fantasy of the normative. “Faggot.” So, I sometimes reappropriate this word. I sometimes attempt typing this word into a Facebook status. I reappropriate in search of closure, but Facebook always temporarily suspends my account for contributing to “hate speech.”

(My body—my desirous body—censored again.)

As I continue to resist heteronormative culture, writing toward and against that plus sign—wary as ever of what Jasbir Puar has called homonationalism—I feel my own excessive poetics is also always-already a poetics of dissent.

My wastefulness is meaningful and my excess is not apolitical.

Overwhelming and dissentious, my mess is deliberate.

5.

Edelman’s talk also has me thinking more about my past post on Decadence and obscenity.

The threat of the non-normative. A queer Decadence. The weapon of poetry itself:

The flowers have to be obscene. There has to be too many of them. They must be considered a nuisance. A threat to Taste. Kitschy. Too much.

The flowers must pose a threat like the ones mentioned in Zack’s recent review of Jeannine Marie Pitas’ translation of Marosa di Giorgio’s Carnation and Tenebrae Candle:

In the poems, the floral explosion on every page seems to become a metonym for femininity. At times, the flowers seem to indicate a sense of solidarity among women that is constantly threatened by the patriarchal order, like when the speaker tries to “calm herself” by thinking “of her grandmother off in the kitchen, making little cakes, burning like roses.” Elsewhere, the flowers appear more as a sign of an idealized femininity, which in its proliferation impedes the speaker’s movements and drowns her in blossoms.

Gazing with their Baroque eyes, Marosa’s flowers inhabit the void, stand outside the norm. The flowers are feminine, dynamic, athletic and, therefore, dangerous.

6.

Contemporary poets should be inventing new flowers and wearing them like green carnations.

7.

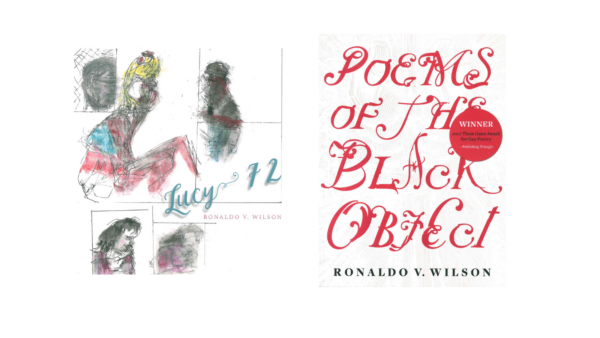

After revisiting Ronaldo Wilson’s Poems of the Black Object, a continuation of Narrative of the Life of the Brown Boy and the White Man, I want to consider the theatrics, choreography, athleticism of Decadence:

This is an act of writing into the fear of fat, which is not about fat but a metaphor for running away from fat into more deliberate forms of excess. This decadent athletics is of a particular moment, the choice to say what I want is to create one version, after another, of a constantly imagining self.

Wilson, who is known for his startling performances, appears to be sustained by a “decadent athletics” grounded in the present of a “constantly imagining self.” A decadent athletics that goes beyond the page, beyond the act of writing. Wilson carries the poems with his body, through a seated audience, bringing changes—new meanings—to his various masks and/or additional props, costumes, etc. Obstructed, Wilson-as-Lucy often appears to be attempting to liberate the Black body, the Black self. It often feels as if the Lucy poems were composed from inside a suffocating mask:

I cannot speak, but when I have to, I hold in my throat, a soft light,

curving forward to the front of my palate.Puddles beam through the air into my eyes. There’s a pattern.

Evaporation, my mark fades on the cement.In there lie my eyes, too, which vanish. My face blanks to nothing.

Nor does my nose matter. No. My eyes.-from Ronaldo Wilson’s “Lucy and Shadow“

Ronaldo Wilson’s 2018 performance at Ciné / University of Georgia (Video)

What is the black object?

On the railing is an abalone’s husk. Its meat is gutted, mother of pearl left to catch ash. What if your face were stripped away from this house? Would you remember red: the hummingbird’s throat?

-from “The Black Object’s Catalyst“

Wilson’s spectacular body (between masks/voices/registers) often becomes the between of visibility and invisibility. When performing work from Lucy 72, Wilson dons a white Lucy mask:

Lucy, via her poetic personae, speaks outside of her perceived race, or is complicit in her race as a white woman, a white woman who is also a fat brown young man, or not black, or shapes, sometimes becoming a flash of light, meditating on people, rocks, playing in rivers, skies, staring into beige walls, fans, or low grass.

(from “The Color Series” essai)

It’s also important to note that the dissentious masque of Decadence can conceal more than a face:

I am suspiciously, yet fully, alive, unthreatened and singular but amidst all the others being marked in the flow of a number of related constructs: visitor, traveler, assailant, voice, spy, dancer, walking into and past that reactive moment as I attempt to wrestle with whom I am playing with, in the space between self-fashioning and experiment.

(from “The Color Series” essai)

For Wilson, the dissentious masque involves costumery, singing, dancing, and multiple masks. In some cases, his audience members actually reinforce the idea of the mask. In this performance, Wilson hands his microphone to a young white woman [33:20], asking her to read from Lucy 72. (She hesitates at first. After all, these are not her poems. Or are they?) Wearing two physical masks, he proceeds to frolic and dance and, making gestures with his arms, the white body becomes mouthpiece. Once triple-masked, Wilson’s body temporarily disappears, becoming the between of visibility and invisibility. Additionally, in this moment, the poet’s Black voice is simultaneously present and not present.

The audience doesn’t quite know how to respond to this ventriloquism, this suspension of reality.

“What if your face were stripped away from this house?”

8.

Visual artist Nick Cave has suggested that his Soundsuits can help a wearer “stand up” to corrupt powers. Similar to Wilson’s performances, Cave’s Soundsuits suspend reality—and the reality of the body. In a reversal of powers, many of the elongated, towering Soundsuits become panoptic. The wearer of a Soundsuit—the previously surveilled—becomes the surveiller. A new gaze is activated.

The wearer also becomes what Deborah Kapchan has called a sound body.

9.

In Keywords in Sound, Deborah Kapchan describes a sound body as “a body able to transform by resonating at different frequencies […] the marked status of human beings, that is, a state socially designated as standing apart from the norm.” As sound bodies—the Queer poet, the Black poet, the Woman poet, the Trans poet—can be viewed as extraordinary precisely because they are non-normative. Sonic and symbolic, the sound bodies, to use Kapchan’s phrasing, “pollute”. Noise pollution.

The poet—as sound body—resists “attempts of the market to harness and copyright sound, the sound body refuses to be owned. It inhabits but does not appropriate. It sounds and resounds but cannot be captured” (39).

Paul Cunningham (b. 1989) is the author of the The House of the Tree of Sores (Schism2 Press, 2020) and The Inmost (Carrion Bloom Books, 2020), and the translator of Helena Österlund’s Words (OOMPH! Press, 2019). He has also translated two chapbooks by Sara Tuss Efrik: Automanias Selected Poems (Goodmorning Menagerie, 2016) and The Night’s Belly (Toad Press, 2016). His creative and critical work has most recently appeared in Snail Trail Press, Apartment Poetry, Kenyon Review, Quarterly West, Poem-a-Day, DIAGRAM, and others. He is a managing editor of Action Books, co-editor of Radioactive Cloud, and co-curator of the Yumfactory Reading Series. He is a PhD candidate at the University of Georgia. @p_cunning