Final Fantasy VII (2020)

1.

According to Bataille in “The Language of Flowers,” flowers can be a “spectacle,” like fields or forests. With their “contortions of tendrils” and “unusual lacerations,” Bataille suggests that a spectator might feel a stronger affinity for a flower (a traditionally elevated image) even though they could grow up out of a manure pile, rather than, say, an underground and unseen root system (a lower image, aka Hell). Here, when thinking about Bataille’s emphasis on the hidden and dirty root system, the etymology of the word “obscene” is important. Coming from the Latin (obscēnus), if something has been labeled ob-scene, this means one of society’s many repressive state apparatuses has decided a particular image should be ob-structed from the view of spectators. The ob-scene is what’s not seen.

But Bataille suggests the obscene need not be hidden underground, specifying that one could determine certain flowers to be obscene depending on whatever society dictates as troubling or perverse:

Other flowers, it is true, present very well-developed and undeniably elegant stamens, but appealing again to common sense, it becomes clear on close examination that this elegance is rather satanic: thus certain kinds of fat orchids, plants so shady that one is tempted to attribute to them the most troubling of human perversions. But even more than by the filth of its organs, the flower is betrayed by the fragility of its corolla: thus, far from answering the demands of human ideas, it is the sign of their failure […] For flowers do not age honestly like leaves, which lose nothing of their beauty even after they have died; flowers wither like old and overly made-up dowagers, and they die ridiculously on stems that seemed to carry them to the clouds (12)

Flowers are Decadent, but not because of their beauty and not because they are flowers alone. Again, they have to possess “contortions of tendrils” and “unusual lacerations.” They might even look “satanic.” Curvy, fatty, swollen flowers – fat-lipped flowers – thought to be suggestive, too stimulating. (Aubrey Beardsley’s drawings were often criticized for their hard lines and flowery corpulence.) Flowers are Decadent because of their filthy beauty! The image of a field of flowers in a poem isn’t Decadent simply because it is an image containing many flowers. The flowers have to be obscene. There has to be too many of them. They must be considered a nuisance. A threat to Taste. Kitschy. Too much.

Hannah V Warren, citing Mary Russo, elaborates on the grotesquely exhausting flower-language in this recent blog post on Helena Boberg’s Sense Violence:

The “she” becomes a symbol of the grotesque, an empty vessel that contains meaning only when in juxtaposition to the male speaker. Mary Russo writes, “The classical body is transcendent and monumental, closed, static, self-contained, symmetrical and sleek . . . The grotesque body is open, protruding, irregular, secreting, multiple, and changing.” Here, the female body fits the grotesque, lacking her own definition. Among other containers, the female body in these poems is a “bluebell,” “a clinic / with room for one,” and “Served / as an oyster.”

Warren later argues that it is the slippage of language, the “excess” that allows the “I” to become multiple, to mock notions of male superiority.

I believe if the obscenity of flowers poses a threat to tasteful or overtly masculine art, then that is precisely what makes flowers a valuable tool for New Decadent art.

Decadent femininity is always a threat to fascism.

2.

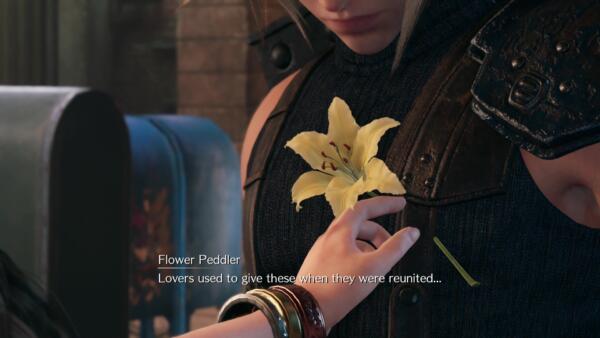

“Yellow flower obtained.” Final Fantasy VII was one of my favorite video games growing up. A gripping, immersive RPG about eco-terrorists risking their lives to save a sick planet from fascism. Supremely Decadent! One of my favorite new additions to the stunning 2020 remake is when Aerith the flower peddler (whose name seems to be an anagram of “Earth”) gifts Cloud a “real” yellow flower. (Flowers are a rarity in Midgar – an impoverished city of factories.) Aerith secretly grows her spectacular flowers under the floorboards of the city’s Sector 5 Slums Church. Flowers become private, risky, pornographic. Aerith describes her flowers as “having a kind of power.”

Aerith’s stash of flowers becomes Obscene and is, therefore, Divine!

Aerith, who like Kirsten Dunst’s character Justine in Lars Von Trier’s Melancholia, appears to share an intense psychological bond with a renegade planet – a living organism – that’s gone off course. “Life is only on Earth. And not for long,” is what Justine tells her sister Claire (played by Charlotte Gainsbourg), who invests far too much of her own energy in “men who study things.” Justine refuses to give in to the horrors of the same world her sister has. Like Aerith, Justine seems to just know things about the planet that the other human characters do not. In Disquieting: Essays on Silence, Cynthia Cruz writes:

Justine is alone in her knowing – no one in her life recognizes her knowledge as knowledge. What does it mean to know without being able to share what you recognize as truth because you are alone with your recognition? Certainly, this isolated knowing alienates Justine and renders her mute and paralyzed. For how long can you point things out to people and have them tell you what you see is not real before you collapse back into yourself? This collapse is one way in which depression and melancholia respond to hegemony (59-60).

This accurately describes how I feel about New Decadence. As depressing as a knowledge of the lasting effects of the Anthropocene might be, an ecologically-driven New Decadent approach to life could actually be a worthwhile response to today’s neoliberal fascism.

In both Final Fantasy VII and Melancholia, it is the women who are psychologically prepared to handle the most harrowing environmental truths, not the male characters. (I have always viewed Von Trier’s male characters as utter buffoons i.e. Willem Dafoe as the bogus therapist in Antichrist.) Like all RPGs, you are given choices in Final Fantasy VII, but there are moments in the game when the choices don’t matter. No matter what option you choose in the linked scenario, Aerith (or Earth) is in control of your fate. She knows precisely what you do not. You cannot reject the taboo spectacle of the yellow flower, a reminder, in the Anthropocene, of human mortality and our past human failures.

3.

As I mentioned in my last blog post (in which I discuss the color yellow’s relationship to Decadence) and in this recent interview with James Pate, there is something unapologetically excessive about New Decadence. And, in contemporary poetry, I keep seeing the word itself – “Decadence” – springing up, flower-like, more frequently. Olivia Cronk, in her new book Womonster, asks, “Did you ever get into the stagnant bath of a real confession? Slip inside into living in a body as a site of decadent filth?” For Cronk, excess is about making selves of a self.

Briefly citing the same Joyelle McSweeney post I used as the impetus behind my “We Are Decadent Again” post, Quarterly West launched their own “Decadence”-themed issue shortly after. I found the issue (and its Introduction) quite strange because many of the poems do not come across as “sick” or “corrupted,” but some do make references to sickness. In fact, a number of the poems are arguably tidy, formatted in tightly woven tercets or couplets. That’s not to say that the lyric can’t be sonically excessive (it sure can!), but the Gothic also feels removed from (not all) but many of these poems. Some are arguably teetering on the cusp of minimalism. These “Decadent” poems do not feel transgressive, degenerative, or thermally degenerative. There is certainly nothing obscene here. It feels more like an anthology of Impressionistic works with, at times, mild Rococo elements (i.e. a lot of the poems incorporate words like “gold” or “golden” etc). Judging by the Introduction, the obscene feels as though it has been swapped out for Arthur Symons’ ideals…

“Now Impressionist and Symbolist have more in common than either supposes; both are really working on the same hypothesis, applied in different directions. What both seek is not general truth merely, but la vérité vraie, the very essence of truth – the truth of appearances to the senses, of the visible world to the eyes that see it; and the truth of spiritual things to the spiritual vision.”

-Arthur Symons, “The Decadent Movement in Literature” (1893)

Later, in the same essay, Symons cites Decadence as what’s “in the very air.” He seemed to want to cure the city cafes of a mysterious pollution. A cure for something that often has no traction in academic circles (i.e. If we split up this ‘disease’ of Art into Impressionism and Symbolism, we can elevate the conversation, we can think we understand how this disease works).

Impressionism and Symbolism are appropriate things to discuss in academia, not just because they supposedly reveal the “truth of the human soul,” but because they are born from out of institutions. They have always been a way to explain Decadence. But Decadence and excess? Such things are still taboo. (Unless of course you’re the British Association of Decadent Studies, wherein Decadence is actually considered a field! Incredible!) In fact, during my early PhD coursework, one professor actually had the audacity to ask me to not write about excess in my essay on R. Zamora Linmark’s Rolling the R’s because “queer excess” was apparently “not specific enough.”

(I never finished writing the essay because I do not want to be cured.)

But, make no mistake, academia did not invent Decadence. Again, while I wasn’t necessarily disappointed with poems by contributors like Brian Clifton and Emily Pittinos, I feel like the New Decadence of our sick world calls for a “contortion” of languages.

New Decadence calls for high-risk poetry.

Poetries-in-translation.

4.

If there’s going to be something called New Decadence in 2020, it must include translations or interlingual works. This is non-negotiable. One need not look any further than Charles Baudelaire’s own “transgressive circulation,” his incredible journey (via translation) into Chinese (where he was referred to as a “demon poet” in the 1920s) and Russian (in what Adrian Wanner has described as Russia’s 1880s pre-Decadence). Later Russian champions of Decadence would include N.M. Minsky, D.S. Merezhkovsky, and K.D. Balmont.

Decadence is not exclusively European. It is always spreading. To this day. It is contagious. It is contagion itself. It’s what’s “in the very air” and it always has been. There are many New Decadents writing today. I think a number of the writers from this Virtual Poetics list that Madison McCartha shared earlier in the season would be a great start:

This topography performs, I argue, a recognizable poetics: a poetics of opacity—a generic instability, a radical refusal—an aesthetic model at once of, but not bound exclusively to, black artistic expression. The writings of Neda Atanasoski and Kalindi Vora, Aase Berg, Simone Browne, Édouard Glissant, Saidiya Hartman, Toni Morisson, and Ed Steck, the work of visual artists Craig Baldwin and Christian Boltansky, and most importantly the films of new media artist Jeron Braxton, provide a grammar with which we might approach this resistant surface—a surface enacting a virtual poetics.

Again, as I’ve said in past posts, New Decadence is about the truth of masks, queer camp, the contortion and crossing of languages, translation and excess – excess above all else. What could possibly be more threatening – contagious and corrupting, pose a danger to America’s gold standards of poetry – than the excess of translation? For example, when people review or read works in translation, there sometimes seems to be an expectation for linguistic mishaps. Or an anxiety in readers (i.e. Am I reading the “best” translation?). Such anxiety is precisely why this blog post by Zack Anderson is so relevant:

This “perfect or transparent copy” is analogous to the rhetoric of “smoothness” that we constantly see in bad translation reviews. The fetish of smoothness simultaneously works to domesticate the translated text and to erase its very medium of translation, preserving the illusion of the original/copy distinction. In matching up modern accounts of fidelity in translation to its sonic counterpart, we find that “fidelity” is clearly not a value-neutral, empirically valid term, but rather a boundary marker for a particular set of aesthetic assumptions. For an analysis of both sound reproduction and translation discourse, this is Sterne’s most salient point: “Fidelity is, thus, confused with aesthetic preference.”

That all said, reviews of books-in-translation are, unfortunately, still pretty rare….

5.

I’ve been thinking about “Digital Fauna,” a recent poem by Ginger Ko where the word “decadent” also pops up:

I like the decadent privacy of text

but a part of it feels mistaken.

Others have taught me

that many harmful things require privacy.

Text offers the “decadent privacy” needed to write, to confront the sick, animalistic “network,” which is also an “absence” and not necessarily a comfort (i.e. the whole of society is sick, therefore the Decadent privacy of writing offers a home-like space, a feeling of belonging). Much of the language in Ko’s poem also confronts “fakes”, ideas of authenticity, images that cause doubt, only portions–parts–of bodies instead of visible (w)holes (i.e. “I think we have a God-facing self that / cannot be entire”; “Who is more sincere?”; “Our minds abuzz but our bodies never completing”; “It’s only in text that I can belong / even brilliantly”). Most intriguing to me is the line:

It’s only in text that I can belong / even brilliantly.

Like the Decadence of the 1890s, it appears to be privacy that offers a safeguard against the normative, toxic whole. But perhaps Ko is also cautioning that if one spends too much time in the shadows (“but a part of it feels mistaken”), they might also begin to experience doubt. Ambivalence. In any case, if it is sincerity that the whole desires, they will only be forced to explore all four “compartments” of Ko’s poem. No easy answers here, but I suggest revisiting this compelling poem’s title.

6.

There is nothing sincere about Decadence. Which is why there is nothing more sincere than Decadence.

7.

Just as Ko raises questions about authenticity, Cronk’s Womonster offers readers a multiplicity of selves. A long poem called “Interro-Porn” announces that it is “for a split voice” and recommends a “Françoise Hardy album.” With influences ranging from the bold and brilliant Grey Gardens (1975) to the exhilarating films of Kenneth Anger, Cronk sets the tone from the very beginning, preparing us for the splitting of a self and a suggested accompanying soundtrack that only enhances her already cinematic poetry.

Below, we come across two very different voices. The interrogative all-caps voice that might very well be an amalgam of a trio of evil stepsisters ready for their reality TV close-ups: Drusilla, Griselda, and Giselle. And the second voice? A Womonster (?) addicted to “pretend,” searching for the next enthralling thing that will give her pleasure. Similarly, Cronk, with her playful, comic style, tempts us to also search our souls, block our own scenes:

WHY CHOOSE

TO SMOOTHE MY WOMEN INTO OUTFITS?I CHOOSE IT.

As a girl, I cut women from my grandmother’s catalogs (mostly plus-sized clothing for work and vacation) and made paper dolls. When I ran out of those, I drew pictures of women with perms, in office outfits and in commuter gymshoes over bobby socks and pantyhose. I drew women with bangles, can still remember perfecting the line around a wrist, a trick I now do for my daughter, when she asks to be drawn as a princess.

The all-caps voice constantly questions the Womonster’s authenticity:

DID YOU WATCH THE RIHANNA VIDEO TO RIP OFF HER STYLE?

AND A FLEETWOOD MAC, TOO??? WHERE DO YOUR PLEASURE,

YOUR THIEVING END?DID YOU ever get into the stagnant bath of a real confession? Slip inside into

living in a body as a site of decadent filth?

The theatrical weaving of voices suggests that Womonster is not a thief, but an assemblage of many parts and many influences. Olivia Cronk’s Womonster embraces the monstrous and the multiple. Rejects the male-authored objectification of women. In fact, the Womonster feels reminiscent of Johannes’ past post on “the voice of interiority” and “occult transmissions.” Like Nathalie Djurberg’s animated assemblage, Cronk’s bold and uncompromising Womonster feels as though she’s made from many different voices, outfits, records – all of them loud!

The final section – “Chenille” – remains an intriguing mystery to me. I kept thinking of literal chenille fabric as I read this section, recalling the aforementioned quotation (“WHY CHOOSE / TO SOOTHE MY WOMEN INTO OUTFITS? / I CHOOSE IT”). In “Chenille,” Cronk writes:

what kind is I

my

family makes hole family is a translation afterall after what

I do not know if others prefer constraint as I do.

In all settings in which I operate, I choose not to choose.This is to leave left compulsive and hedonistic a system.

I avoid losses by not keeping the keep of doors.

Cronk’s speaker, opposite, in this case, to the obtrusive interrogative voice, must make do with the “hole” family, rather than the “whole.” She chooses “not to choose.” Translation is the only option. She must fill in the gaps. Cronk is not interested in “keeping the keep of doors,” but the freedom that Decadence demands. The so-called whole is always “hole,” always an emphasis on the parts.

Paul Cunningham is the author of The House of the Tree of Sores (Schism2 Press, 2020) and the translator of Helena Österlund’s Words (OOMPH! Press, 2019). He has also translated two chapbooks by Sara Tuss Efrik: Automanias Selected Poems (Goodmorning Menagerie, 2016) and The Night’s Belly (Toad Press, 2016). His creative and critical work has most recently appeared in Snail Trail Press, Kenyon Review, Quarterly West, Poem-a-Day, DIAGRAM, and others. He is the managing editor of Action Books, editor of Deluge, co-editor of Radioactive Cloud, and co-curator of the Yumfactory Reading Series. He is a PhD candidate at the University of Georgia. @p_cunning