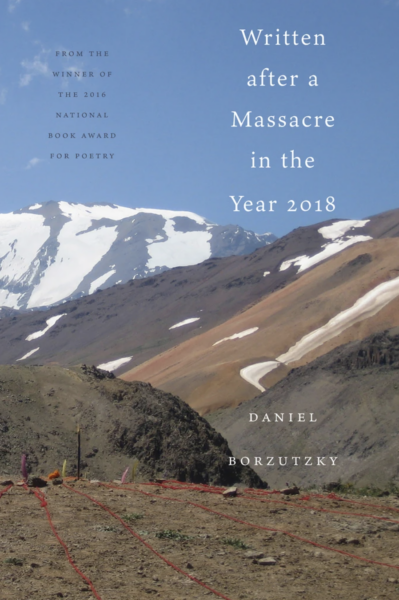

Written After a Massacre in the Year 2018 by Daniel Borzutzky

“The poetry of the shattered bone / in the flame of the human document.” This is a broken god of a book. Eyes filling with worms, mouths stuffed with iPads, the reproduction of dead children, the border that “keeps inching closer”—it’s all there in the immensely engaging poems of Daniel Borzutzky, an artist I’ve long admired for his tireless protest against state violence, carceral capitalism, and white supremacy. As early as his third book, in the murmurs of the rotten carcass economy, the poet writes,

We want you to know that as we slip away we can see things for what they are: towers of sand form across the garden and in them are small explosions that go silent only when we speak about what we know we cannot speak about, about what we only wish to speak about to keep ourselves from speaking about what we do not want to say (58).

Then and now, Borzutzky dares to write—to confront—the unspeakable: the atrocities of capital. In his nightmarish sixth collection of poetry, Written After a Massacre in the Year 2018 (Coffee House Press, 2020), Borzutzky’s poems continue to murmur the ghost languages and unimaginable cruelties of our world: its surveillance tactics, its tactical warfare, its caged babies, its corrupt bankers, its private sectors, its privatized air, its foreclosed mouths:

They dream of a massacre that can take place in public and in private

at the same timeThey like to watch us as we look into each other’s empty faces

They like to hear us say that was the one I loved

We forget our bondage

We are not yet dead

We are at the border of the before and after (79)

These are not just poems of compelling witness, but unimaginable, unforgettable songs of grief.

Wet Water Hill by Lily Duffy

Lily Duffy’s poetry is the rare electrifying kind, the kind that makes a jaw tremble. Vivid, gorgeous writing. With “varying degrees of submersion,” Wet Water Hill (Garden Door Press, 2021) delves into a childhood tide of inkblot faces and mysterious objects, offering readers a gripping story of a young woman’s meditations on desire—as told through various memoryscapes: a waterpark, a friend’s basement, a pine-pavilion. “A camera falls down a glowing green esophagus / Light scatters from my eye; I realize I’m the camera.” Invoking Alice Notley’s In the Pines, Duffy is a fearless poet who fills the sound of water with immeasurable, ghostly light.

Active Reception by Noah Ross

“the w(h)ole assembly, line threading knots, through a larger, web, of entanglements, since found myself swimming, in spiders, that won’t drown, nor, I, nor these holes, nor these books, that won’t drown, nor I, in the space, of capital.” How can I begin to describe the satisfying strangeness of Noah Ross’ Active Reception?—a layered, multi-sensorial book with maximalist flavors that’s sure to stun readers and critics. New “co*formations” of language swell and burst at the hellmouth center of Ross’s “cheek”/”(w)hole”/”ch/eek” triptych. To write a “poetry of bottoming,” as Catherine Chen recently described it, the poet uses parentheses, slashes, and ampersands to explode and reimagine category (“cate/glory”), admitting he must be “numerous” and “expansive” in his approaches to poetics, gender, and the equally massive violences of the state apparatus.

As readers descend even deeper into the slash-heavy layers of a corporate-sponsored Hell called THE APPARATUS, an Acheron-like river of prose runs along the bottom of the pages detailing the gendered history of the word cinaedus. Once consumed by the dark truths of “(w)hole,” Ross’s language puckers and gyres forward, code-cracking, eek-ing, and leaking a story of the speaker’s “passage from biopower to bottom power to power bottom / to bio bottom.” By the time you cross from “cheek” to “ch/eek,” you’ll swear you’re spying Os in every sentence. Yet another book brilliantly designed by Nightboat’s own Rissa Hochberger, Active Reception—a book of words or worlds, holes or wholes—is visual ecstasy and Noah Ross is a true radical.

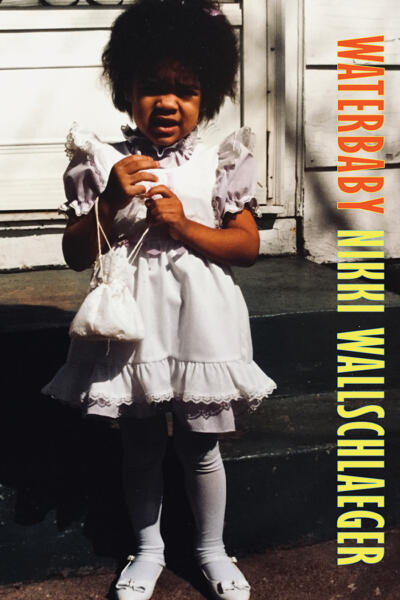

Waterbaby by Nikki Wallschaleger

“Little rabbits who relax their hair in locked bathrooms / Little rabbits hiking in dormant volcano landscapes / Little rabbits who crack their gum when the bells rings.” Like the unpredictable rhythm and tempo changes of James Booker’s “Black Minute Waltz,” Nikki Wallschlaeger’s Blues-infused poetry collection crashes and quakes with the frenzied spirit of artists like Etta James, Wanda Coleman, Jimi Hendrix, Kurt Kobain, and many others. It’s a stunning “stone-sore” book, an altar of the self, a comfort to any American tired of waking up tired. Waterbaby, a book written in response to the loss of a loved one, looks to water for relief, understanding:

I, Nikki, as a contemporary

woman, am bound to ask

who’s spiraling in the faucet (22)

In “Middle Passage Messaging Service,” Wallschlaeger writes of a “waterlogged lifesickness,” juxtaposing tears with laughter (“to laugh so hard / is to cry writing with the smoke is the word”). The tears come again in “The Lunch Counter of Eternal Tears,” but they arrive in the form of absence:

Instead of crying his shoulder I build a fountain of black amethyst

in an artificial square. Instead of crying I ring the bells of a bottomless

road. Instead of crying I listen to Roy Orbison’s “Crying because the

way he waterfall-sings “crying” feels like a worn leather booth that

wouldn’t refuse me service (59)

In “Valley of Things,” the “value of thingification” is what hangs over the riverbanks of the natural world. Wallschlaeger knows “yesterday’s news is greener,” as we wake up each new day at odds with the threat of the hyperobject known as climate change. (This theme appears again in poems like “Dirt Floor,” in which the poet laments the dying coral reefs.) In “Valley of Things,” the speaker finds beauty in a child throwing an unnamed object to the ground, followed by a celebration of the natural world (“a good poet prays to nature”). The maternal—the natural—also pools in “Women Are Doomed to Be the Angels of Love”:

Lisa Frank-style, engorged with crusty satin hearts. I pronounce my

name with an embarrassingly hearty accent. My colostrum pools with

the plumping of an inflamed heart,inspired by the nutritional needs of my babies. Hearts are spray-

painted on trains like talismans, guiding me eventually to the Heart

Afterlife where my treasured friends exist in heart time (20)

Four poems in particular (“Nobody Special”; “Blue Flame of July”; “Why Do I Feel So Old When I Look So Young”; “Crash Blue Sunday”) read as a musical outfit of Blues songs. The speaker becomes singer. I am reminded of Fred Moten’s thoughts on “sonic shimmer” and the homophony of cymbal and symbol, the relationship between image and motion. Like the tears that have yet to fall in “The Lunch Counter of Eternal Fears,” the spectacle of “homemade confetti” in “Nobody Special” is “ready,” but as readers, we do not get to see the confetti fall. Instead, the speaker/singer of a “long night” repeats “I’m nobody special, nobody special” into the darkness, yet the poem concludes with a hopeful and seemingly infinite “flickering, flickering.” Another verse, which I won’t soon be forgetting, comes from “Blue Flame of July,” where time itself seems “beyond repair”:

A broke clock is right twice a day

don’t mean I’m gonna be healingAny fool can make the rules

any fool will follow themI know in my soul that’s right (37)

Wallschlaeger’s nimble poems, like wild little rabbits, will startle and “snarl back when you least expect it.”

Paul Cunningham is the author of the The House of the Tree of Sores (Schism2 Press, 2020) and his latest chapbook is The Inmost (Carrion Bloom Books, 2020). He is the translator of Helena Österlund’s Words (OOMPH! Press, 2019) and two chapbooks by Sara Tuss Efrik: Automanias Selected Poems (Goodmorning Menagerie, 2016) and The Night’s Belly (Toad Press, 2016). He is a managing editor of Action Books, co-editor of Radioactive Cloud, and co-curator of the Yumfactory Reading Series. He is a PhD candidate at the University of Georgia. @p_cunning