Near Dark (1987) Directed by Kathryn Bigelow

JP: Hi, Paul. First of all, congratulations on your upcoming collection from Schism Press. I’m really looking forward to reading it! I also really liked your essay about Decadent literature on the Action Books Blog (“We Are Decadent Again”). Huysmans’ A rebours, which is mentioned, is one of my favorite novels of all time. I stumbled across a copy of it in a bookstore when I was in high school, and was stunned by the feverish, ornate prose style, and by the whole notion of treating the senses as a means of almost mystic exploration (there’s an entire section simply on perfumes). And I think your point about Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray being both an example of Decadent art and a work of Gothicism is a very interesting insight and could maybe apply to Huysmans’ novel as well. Jean des Esseintes is such a vampiric figure! In terms of this relationship between the Gothic and the Decadent, how would you describe it? Are there certain elements that one emphasizes more than the other, or do you see the relationship as being more shapeshifting and difficult to categorize?

PC: Thank you! I’m so grateful that Schism was willing to distribute an interlingual poetry collection. I’m thrilled! Also, I love your question. A rebours is great! I’m a big fan of the Brendan King translation. And Là-Bas, too. Equally excessive, feverish prose. I see the relationship between the Gothic and the Decadent as being more difficult to categorize. I wonder: is the Gothic more concerned with night than Decadence? Both certainly share an affinity for monstrosity. (And it is often the monstrous that consoles and fascinates Des Esseintes—works by Redon, carnivorous plants, carnal pleasures, etc.). Though, when I read your book—Flowers Among the Carrion—I found myself thinking of vast, monstrous night as a hyperobject in the same way Timothy Morton has approached global climate change as a hyperobject. If night is a metaphor for the unknown in the Gothic, then I can understand why Gothicism keeps springing up in contemporary poetry. It feels like an appropriate response to global climate change. Perhaps, metaphorically, Decadence embraces night—inevitable death. But Decadence also feels like a warming. Warming like the earth itself. Burning up like Walter Pater’s “gem-like flame” or what about Des Esseintes’ description of Gustave Moreau’s sublime painting of Salome:

“Under the scorching rays emanating from the head of the Baptist, all the facets of [Salome’s] jewels had caught fire; the stones had come alive, outlining the body of the woman with incandescent flashes; picking out her neck, her legs and her arms in points of fire, as vermillion as glowing coals, as violet as jets of gas, as blue as burning alcohol, as white as the rays of a star. The horrific head blazes, still bleeding, leaving clots of dark purple on the ends of the beard and hair” (86).

I want to be clear that I don’t think the light or flame of Decadence is the same thing as the contrasting “daylight” (optimistic, good-humored U.S. poetry) you mention in Flowers Among the Carrion. I think Decadence is more of a fleeting, blood-stained light—fueled by sickness and oppression, society’s wars and violence. It is the last moments of light just before nightfall. That might be one small point of differentiation between the Gothic and Decadence. I’m not sure if that kind of explosive light is characteristic of the writing found in many Gothic novels or poems, but the Victorians’ intense fear of the heat-death of the sun would be another reason for such consistently fiery prose. In any case, both share a focus on mortality that could be useful in approaching the Anthropocene.

JP: That’s a really fascinating description of Decadence – I really like the way you link it to warmth and light (though, as you say, “a fleeting, blood-stained light”). And Walter Pater – I love Pater’s writing…All of those lush, otherworldly descriptions.

I like your political reading of Decadence as well, which you also bring up in “We Are Decadent Again.” Wilde has a great essay called “The Soul of Man under Socialism,” which argues that Socialism, instead of bringing about mass uniformity (as the Right often claims), would actually bring about a flourishing of diversity within human experience, so that each person would have the time to follow/create their own path.

Once we were no longer defined by work – once we transformed work by having much shorter work weeks and an equality of resources – we would no longer define ourselves by the marketplace’s normalizing standards. As Wilde writes, “One’s regret is that society should be constructed on such a basis that man has been forced into a groove in which he cannot freely develop what is wonderful, and fascinating, and delightful in him.”

If Decadence is sometimes defined as emphasizing the parts instead of the whole, in contrast with classicism, which tends to emphasize the whole instead of the parts, then Wilde’s conception of Socialism would be a Decadent Socialism. And Marx’s own writings sometimes align with this idea, too. Once the necessities were taken care of, he envisioned this great expansion of human freedom. Solidarity doesn’t mean uniformity in either Marx or Wilde.

I think there’s a real fear of this, though, in our culture. “Idle hands are the devil’s tools” and all that. Capitalism has a thousand different ways of convincing us that the most important people are busy people – that human worth is tied up to how much we produce (in either the literal sense, or the more abstract sense).

I think this is tied up to our capitalist experience of time, too – how the latest, the newest, the most up to date is valorized in our culture, and how this shrinks time into these very small slices that, at the moment, feel absolutely totalizing. I like to imagine that Socialism would edge us to a very different experience of time – a multi-layered occult time, a spectral, ephemeral time.

One of the things I like about the Gothic is how it frequently has this element of ephemeral time. Many of my favorite Gothic horror films are associated with “slow horror” – Dreyer’s Vampyre, Gunn’s Ganja & Hess, Herzog’s Nosferatu, Kubrick’s The Shining, Kate and Laura Mulleavy’s Woodshock, Feigelfeld’s Hagazussa, the third season of Twin Peaks.

I’ve been thinking of your poems about empty malls – about mall-space as a kind of ruin – in relation to this aspect of the Gothic (this fascination with the ephemeral). As you write in one of the poems, “Chains and masks and drama in this mall / but there are no people in this mall.” How did you come about such an intriguing project for those poems?

PC: I’ve always loved the line from “The Soul of Man” that goes: “Why should [the poor] be grateful for the crumbs that fall from the rich man’s table?” Charity is the illusion of progress itself. Its effect is only temporary. Feeding the homeless isn’t the same thing as housing the homeless. The “whole” of society is sick and the individual is “starved” so, as Wilde argues, individualism is “what through Socialism we are to attain.” I’m intrigued by your idea of a Decadent Socialism. Especially since Wilde describes democracy as “the bludgeoning of the people by the people for the people.” He also cites “revolt” and “individualism”—Decadent Socialism?—as a threat to a degraded and despotic democracy. Not to mention the revelry! The very Art that accompanies such Decadence.

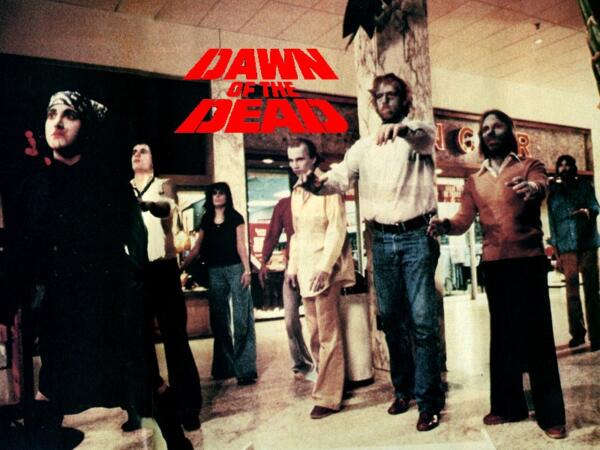

As for malls, they fascinate me for a number of reasons. Growing up, I was most definitely a mallrat. (I think of a mallrat as a sort of flâneur. Let’s call it mallrat flâneurie!) I didn’t have many friends in high school and I thought of myself as a misfit. Naturally, I hung out with other misfits in the mall arcade—an assortment of degenerate, effeminate boys who wore black skinny jeans. Malls have always represented a kind of escape for me. At the same time, I think malls are synonymous with horror, apocalypse, ruins, etc. Especially in Pennsylvania. I grew up a couple towns over from Hopewell—a small town where my father grew up, the same town where George A. Romero shot the opening cemetery scenes for Night of the Living Dead. In 1978, Romero used the Monroeville Mall as the shooting location for Dawn of the Dead. And Pittsburgh has been hosting an annual Zombie Walk now since 2006.

I wrote a lot of my mall poems while translating Helena Österlund’s Words. I felt infected by her repetitive style and, when you spend that much time in someone else’s head, your own style begins to feel transformed. What really inspired the project was this video—which I guess was part of an interesting trend of adding music to images of abandoned malls. There is just something so haunting about Brian Wilson singing to no one. And the forgotten withering tree. I started thinking about Jane Bennett and object-oriented ontology. I guess you could say I tried tapping into a forgotten plant consciousness. What happens when the humans abandon the mall and the plants reclaim it? What happens if the plants thrived in the ruinous mall instead of withering away?

Dan Bell curates a Dead Mall Series on YouTube and I somehow—maybe stupidly?—feel bittersweet about the death of malls. On the one hand, it’s the end of a capitalist empire, but I think it’s also the end of an important social arena. Michael Galinsky’s popular mall photographs almost feel like another world now.

I have to also recommend Anne Friedberg’s book Window Shopping. She has some fascinating things to say about malls and spectatorial flâneurie:

“The mall is a contemporary phantasmagoria, enforcing a blindness to a range of urban blights—the homeless, beggars, crime, traffic, even weather. And, while the temperature-controlled environment of the indoor mall defies seasons and regional environments, the presence of trees and large plants give the illusion of outdoors. The mall creates a nostalgic image of the town center as a clean, safe, and legible place, but a peculiarly timeless place.”

Again, the dying mall might actually be the perfect metaphor for the sick whole (a la Regenia Gagnier) in terms of Decadence. These days, we don’t get to see, with our own eyes, Jeff Bezos’ mistreated Amazon employees. We can’t tell if a building is falling into ruin. We just click a button and wait for the products to arrive at our door.

JP: That’s a great video! It’s so haunting, and has such an intense sense of absence. It reminds me of a passage in Mark Fisher’s The Weird and the Eerie, where he hypothesizes that maybe one reason we tend to be attracted to ruins is that the cohesive symbolic sense of the structure has faded away. Contemporary buildings and structures we can “read” fairly easily since they’re part of a common symbolic language, but older, ancient structures were built within a symbolic system we can no longer entirely see/interpret – and that lends them their strangeness. How will the ruins of malls (if they still exist) be experienced one hundred years from now, or even a thousand years from now? That video – and your poems too! – very much create that sense of the ruins of the present.

And this reminds me too, going back to your essay, of a line you quote from Johannes: “I read poetry for the ruins…” I completely agree with this. When I read, I’m always aware of this sense of absence, that the poem or novel or essay is a sort of ghost script, and that in the act of reading, or imagining this world, I’m participating in this spectral phenomenon, I’m becoming a ghost myself. That emphasis on ghostliness, absence, is the aspect of deconstruction that I always found most fascinating. Derrida once argued, “The cinema is the art of ghosts, a battle of phantoms.” I would say that’s true for all art. The obsession with presence and the rage against absence is, to me, closer to real nihilism than what so-called “nihilism” often is…

I’m currently reading Candice Wuehle’s Death Industrial Complex, and it really does feel like it’s poetry as a form of séance, of mediumship, brimming with lines like “All my life / i had been speaking in a partial / language. Now i can tell / the names of the shadows under / the shadows.” And in your essay, there’s a line that really stuck out to me that relates to this: “I feel like all these things – a Decadent, a Graveyard Poet, etc.” I like how the line goes against the notion of writing being linear. One of the aspects of the Conceptualist era that I really disliked was the frequent rhetoric of how anyone who wasn’t on-board with Conceptualism was irrelevant, not part of the all-encompassing zeitgeist, the “now” – as if writers were obligated to create in this lock-step fashion, and as if every “now” isn’t radically plural and diverse. How would you describe your own sense literary lineage? And how has that influenced your poetry and translations?

PC: I think I have a general disinterest in linearity. Even when it comes to how I think about the Anthropocene. Scholars can piss and moan all day about when we should begin measuring the irreparable damage (i.e. Does it begin with the Industrial Revolution? Deforestation and the sixteenth century sugar economy? The earliest years of the Little Ice Age?), but the bottom line is: the earth’s glaciers are melting, the oceans are warming, and things are really bad right now. If you’re too busy trying to sell the public on yet another “Capitaloscene” book or “Fill-in-the-blank-O-scene” or whatever clunky variation on “Anthropocene” you’ve concocted, all you really might be interested in is careerism? I feel like people don’t like the “Anthropocene” word because it lays the blame on anthropos, but I happen to think some accountability is valuable? I think it has to be about balance. Visualizing an earth without you can be valuable. The human species has changed and continues to change our planet’s makeup. And, believe it or not, we can discuss the human species without arguing for racial invisibility. White scholars need to realize that there can be such a thing as a plurality of Anthropocenes. There are Black, Asian, Indigenous Anthropocenes, etc. And the way we measure such things doesn’t have to be dependent on Indigenous disappearance, which Matt Hooley has written about. I strongly recommend reading Roy Scranton and Matt Hooley.

So, that all said, whether I think of myself as a Graveyard Poet leaning into Night, a Gothicized Decadent, or a zombie-Romantic, there’s a lot of influences at work in my poetry and I see all of those things as valuable to how I proceed—in the Present—as what some might call an Anthropocene poet. If I had to attempt a chronology of my own literary lineage, it might sound unreal, but I was gifted a copy of Aase Berg’s With Deer (a bilingual edition from Black Ocean) when I was 17 and that’s when I started learning Swedish. With Deer was the first bilingual edition of a book of poetry I ever owned or read. During my mid-teens, I thought of myself as a fiction writer, not a poet. My father knows some German, so I always figured I would eventually learn German, but the Swedish stuck. Johannes’ Aase Berg translations (and translator notes) were a big influence on me. I had never (and still have never) read anything like the poetry of Aase Berg. She and Johannes are, unequivocally, the reason I am a poet-translator.

Charles Henri Ford by Cecil Beaton

You could probably say everything about my poetic lineage has been backwards. A fascination with Aase Berg led to Tomas Tranströmer and more Black Ocean titles, which led to Zachary Schomburg (especially his poem-films) and James Tate, which led to surrealism and Rimbaud and Breton, and Breton’s homophobia led me to Charles Henri Ford and his incredible diary—Water from a Bucket—which led me to Djuna Barnes and Gertrude Stein, which led to my discovery of Harryette Mullen’s Recyclopedia. And I just kept reading more and more contemporary books in translation. In my late teens and early twenties, I was pretty much only reading poetry in translation. During my MFA, Joyelle McSweeney recommended LaTasha N. Nevada Diggs, Hannah Weiner, and James Merrill. All three writers have had a significant impact on me! I feel like, to this day, I’m still carrying around all these names, all these bodies of work. For me, lineage feels interchangeable with contagion.

In my interview with Aase, she describes translation as a type of “hacking.” Hacking, infection, etc. I think that’s a productive way of approaching translation. So far, I’ve only translated Swedish women. I feel like I wouldn’t be where I am today if it wasn’t for women like Aase, so I feel indebted to women artists. I guess that’s why, being a queer poet-translator, I’ve also thought of translation as a form of drag. I think I’ve mostly explored these feelings of translation-as-drag in the films I’ve made for Sara Tuss Efrik. Films in which I have altered my voice and dressed up like a Little Red Riding Hood zombie, etc. I’m also currently working on an original bilingual prose collaboration with Helena Österlund—a story about a woman who grows a second head.

Translation always feels like collaboration for me. Like I’m inhabiting the form of another.

JP: I remember reading Johannes’ translations of Berg’s work back when we were in grad school, and being really taken with how utterly different her poems were from what was fashionable in U.S. poetry at the time. There were a few poets like Edson and Simic whose work hovered around the edges of the Gothic, but, in Sweden, Berg was taking this full-on plunge into Gothic Night. I was watching a lot of Kenneth Anger films at the time, and, in my mind at least, there seemed to be a connection between the two – how a film like Scorpio Rising and a poem like “In the Guinea Pig Cave” both have this feverishly stylized nocturnal quality. And I certainly responded to Berg’s work much more than to a lot of the contemporary poetry being written in the U.S. during that time (which was the late 90s). I think that’s one of the many reasons why translation, and reading works in translation, is so important. Sensibilities, poetic or otherwise, are so diverse and mercurial, so counter to linearity and categorization, and translation helps emphasize and add to that aspect of writing – that chaos.

It has been great speaking with you, Paul, and I can’t wait to read your book!

James Pate is the author of The Fassbinder Diaries (Civil Coping Mechanisms), Flowers Among the Carrion (Action Books), and Speed of Life (Fahrenheit Press). His book reviews have appeared at 3:AM Magazine, Tarpaulin Sky, and Sublime Horror.

Paul Cunningham is the author of the The House of the Tree of Sores (forthcoming from Schism Press in 2020) and the translator of Helena Österlund’s Words (OOMPH! Press, 2019). He has also translated two chapbooks by Sara Tuss, Efrik: Automanias Selected Poems (Goodmorning Menagerie, 2016) and The Night’s Belly (Toad Press, 2016). His creative and critical work has most recently appeared in Snail Trail Press, Kenyon Review, Quarterly West, Poem-a-Day, DIAGRAM, and others. He is an associate editor of Action Books, editor of Deluge, co-editor of Radioactive Cloud, and co-curator of the Yumfactory Reading Series. He is a PhD candidate at the University of Georgia. @p_cunning